Community-led and participatory approaches to climate action in the built environment

16 May 2022

This series of 10 interviews with participatory and community-led initiatives around the world provides insights on strategies to incorporate strong community participation and ownership in built environment projects. This work is grounded in the “meaningful participation” cross-cutting Principle of the Framework for Dignity in the Built Environment.

There is a global urgent need to transition from polluting to more sustainable ways of producing the built environment. It is key to do so in a just way: ensuring there are no disproportionate burdens placed on certain population groups, especially those most vulnerable; as well as ensuring the benefits of the energy transition are distributed equally among people. While climate justice calls attention to the social impacts of climate change, a Just Transition calls for consideration of the social impacts of climate action.

In addition to social dialogue with workers, a fundamental component of what that ‘justice’ looks like in practice, is the cross-cutting human rights principle of meaningful participation. The way the built environment is planned and designed has a direct impact on the quality of life of people. This includes who participates in the decision-making and whose points of view, needs, and interests are considered.

According to the UN, “equal and meaningful participation” requires genuine political will, an emphasis on agency and a shift in mindset to realise the value of contributions from all actors: especially those in risk of discrimination or exclusion. Participation processes in the built environment should be co-designed, impartial, timely, accessible, inclusive, gender-responsive, and representative. This enhances legitimacy and strengthens the ownership of community actors.

The strategies and methods for community engagement vary in terms of who initiates them and the strategies used - from consultations, workshops, interviews, ‘discussion days’, data analysis and mapping, to ‘Stakeholder Advisory Boards’, and a Community Development Fund – but certain threads reappear in several of the interviews:

- the importance of involving the entire community of actors from the early stages of a project

- power dynamics, and the importance of participatory processes reaching key decision-makers and resulting in concrete change

- the need for investment in ongoing structures of participation that enable engagement over long time-spans

- and the way in which the processes themselves, if effective, have value and build resilience – in terms of relationships built, mindsets challenged, and strengthened community infrastructure.

Challenges, conversely, vary more widely depending on the context. Some organisations face lack of a culture of inclusion and therefore of political instruments for participation, in some other contexts people’s empowerment capacity has been undermined, while in other countries those aspects are a given and instead the challenges revolve around effective communication, technological tools, and investment.

POCAA, Bangladesh

How can the ‘Platform of Community Action and Architecture’ work with local governments and communities to facilitate participation?

In 2013 a group of architects in Bangladesh were questioning the role of architects in making people’s lives better, and how to reach people who are not able to commission their work. They created the open platform, POCAA (Platform of Community Action and Architecture). The group’s members do work with communities on pro bono neighbourhood improvement projects, including housing and multi-purpose spaces such as urban gardens.

POCAA is affiliated with wider networks, the Asian Coalition for Housing Rights (ACHR) and the Community Architects Network (CAN) which is an Asian regional network of community architects and planners, engineers and academic institutes.

IHRB spoke with POCAA’s Mahmuda Alam.

Strategies and factors of success

Working in cities such as Jhenaihah and Dhaka, POCAA conducts in-depth three to seven-day workshops with community members on what they would like to change in their neighbourhoods, and creates proposals for putting forward to the city council. The process itself opens up dialogue and builds trust. POCAA also sees its role as networking: connecting isolated actions and citizen initiatives already underway in the city with the public administrations’ decision-making spaces.

“We need to hold hands and make our networks bigger, the professionals and community together.”

See this video “How to 'organically' scale up collective movement of city, neighbourhood and housing development?” which is an example of co-planning and co-creation activities in Jhenaidah by the Community Architects Network (CAN).

Challenges

In general, cities in Bangladesh do not engage in participatory processes with residents:

“The city council does not use participation at all, so does not even try to build a false consensus. They just take the big decisions they want within 1-2 days with no participatory processes at all. Therefore, just listening to our voices is activism. We want to create those examples that citizens can be active agents and can do a good job, if given the chance.”

Also, while non-governmental organizations (NGOs) do much good work on the ground, POCAA also highlights a challenge with “top down” NGO strategies, which suppress social innovation by providing external solutions with external resources, rather than creating wider conditions of possibility within the local context from which communities’ own solutions can emerge.

Looking ahead

Looking to the future, POCAA would like to scale up its direct advocacy with city councils. In addition, its work has inherently evolved into building community resilience to climate threats.

“We have been working on physical spaces and better living quality. There are so many other rights that are connected to this. We figured out that when people not individually but collectively can work towards an action or solving a problem, they also somehow achieve the resiliency against those problems of climate threats. So, this is also a new realization for us. We were not just doing something specially designed for climate change but we realized that having a resilient community already addresses that issue. So now we are trying to see how collective action can solve many different problems related to climate change.”

See also this POCAA video about “Co-design of collective housing and settlements”

n’UNDO, Spain

How can not-doing, re-doing, or un-doing urban interventions bring more benefits to social and environmental sustainability?

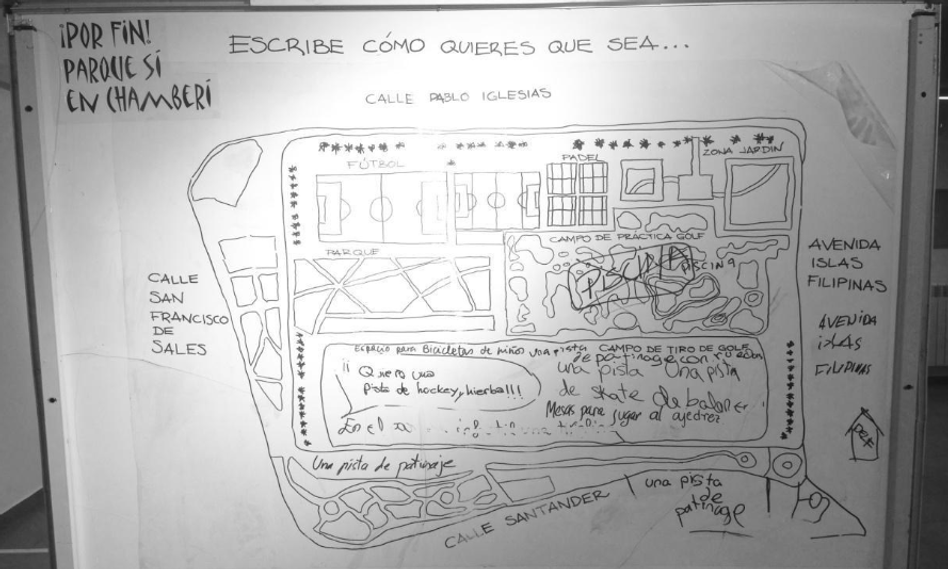

The “Parque Sí' Platform” (“Park Yes” Platform) consists of several neighborhood organisations in the Chamberí district of Madrid. After several years of activism, in 2016 the Madrid courts agreed to convert a Golf course back into public space.

Residents hired n’UNDO (an external architecture/urbanism technical office) and Red de Saberes to develop a participatory process to gather residents’ visions for the new public park, bring a technical feasibility perspective, and present them to the Madrid Municipality.

IHRB interviewed Beatriz Sendín Jiménez and Gonzalo Sanchez from n’UNDO.

Strategies and factors of success

Sanchez and Jiménez emphasized that having a strong core group of Parque Sí residents dedicated to the cause over many years was crucial. And finding different ways for people to participate and share their ideas, despite their time constraints. The group combined workshops, discussion days, and voting dynamics, with the aim of gathering ideas and then compiling them as a “map of desires”.

"The key is dialogue: the more interaction and understanding there is between the different actors, the better, and for that, you need time, attitude, and a willingness to listen."

Challenges

The main barrier was the group’s struggle to have a fluid and fruitful communication with the public administration who would ultimately act on their recommendations, and challenges in enabling participation from as wide a group as possible.

“There are not many social or political structures that support participation processes, so the process demands a lot of energy, time and commitment from the people, and limits the profile of those involved.”

To overcome this, n’UNDO says that public policies that allow participation are important – for example a mandate for companies to allow their employees some time off to participate in these processes, or “urban forums” that strengthen ongoing dialogue platforms between residents and the government.

n’UNDO also flagged that in urban interventions there is usually a rush for immediacy driven by political interests to show results. They would like to see longer and more flexible projects, allowing the temporary and experimental use of spaces to see what works, and what needs to change.

On n’UNDO’s approach to design and building

n’UNDO’s approach is to improve economic, social, cultural and environmental outcomes in the built environment through “not doing, re-doing, or un-doing”, respecting what is already there and minimizing the use of resources.

“The way to be truly sustainable is by reducing our impact, and that has to be done also from architecture and urban planning… following principles of minimal intervention.”

ForumDD, Italy

Finding skills, knowledge, and solutions in the people through the ‘Forum On Diversity And Inequalities’

ForumDD is a coalition between civil society organisations and researchers to advocate for shared causes as a larger entity. It aims to design public policies, proposals, and collective actions to reduce inequalities and enhance diversity, while building consensus and commitment towards these proposals.

The Forum is composed of eight organisations: Action Aid, Caritas Italiana, Cittadinanz Attiva, Dedalus Cooperativa Sociale, Fondazione Lelio e Lisli Basso, Fondazione di comunita' di messina, Legambiente, and UISP.

IHRB spoke with ForumDD’s Giovanni Carrioso regarding their ‘social and environmental justice’ proposal for the use of pandemic recovery funds in Italy.

Strategies and factors of success

ForumDD aims to give space to different sources of knowledge – researchers, policy makers, and especially to citizens themselves.

“We let ourselves be guided by the idea that society’s skills are widespread and that part of the solutions to problems are owned by the same people that experience these problems.”

Carrioso highlighted two key factors for success: (1) 'the glue' that keeps the eight organisations working together - underlying common causes at the core of their work; and (2) the importance of partnering with newspapers who are important vehicles to showcase their proposals and initiatives.

Challenges

Being a forum that unites a large multiplicity of actors, one of the challenges is to reach a synthesis of the most important issues for all member organisations. To overcome this, ForumDD works on the ‘easiest’ less controversial issues, like social justice and energy poverty, first to build consensus and trust. They have found success by starting with small concrete problems and jointly advancing towards proposals on larger issues.

Another challenge is the relationship with public and private actors, especially to generate and sustain dialogue with political actors and parties who are usually closed to external proposals from non-traditional sources of knowledge.

“Political parties are not interested or not able to use these [participatory] experiences and translate them into public policies. They don’t know how to collect what is happening in society.”

Nonetheless, working with mayors and local government officials on finding practical solutions has been a good strategy to achieve some receptiveness of politicians towards ForumDD's proposals.

Looking ahead

Important actions within the next months and years for ForumDD include monitoring the implementation in Italy of the EU Recovery & Resilience Fund through active citizen engagement, and research focused geographically on specific poor neighbourhoods, and thematically on energy poverty and social-environmental policies.

“Environmental policies are [currently] ‘social and place blind’, they don’t see the inequalities, don’t want to intervene in inequalities…we want to ensure that on the grounding of these plans local administrations pay attention to social justice when spending the recovery fund resources… There is still space to work on the implementation and [ensure] that the implementation will be a just transition and not only a technological transition.”

Carrioso highlights the large potential for citizens to be active agents in the political space, but experiences of civil participation and engagement are fragmented in Italy. “They do not become a system, they do not reach a critical mass that allows these practices to become the dominant way of doing things”. Therefore, ForumDD will look into linking the existent initiatives of participation, creating ‘citizenship councils’, and enhancing universities’ “third mission of engagement with civil society”.

Endeavour, Belgium

Empty buildings, people’s ideas – how can the Locay platform connect them?

“Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.”

This vision of activist Jane Jacobs has inspired many urbanists for decades, but the question remains: how can citizens actively engage to shape their living environment? Endeavour is a workers’ cooperative that supports this engagement through social-spatial research and innovation, process design and guidance, consultancy and activism.

An example of this happened in 2016, when the City of Antwerp put the 'Den Oudaan' police tower up for sale. Endeavour and friends started what became a city-wide cooperative movement to collectively buy the 10-million euro building. Read the full story here. While the tower was sold to someone who offered 2.5 times the asking price, the process kick-started future steps.

This is how Locay started. Today it is a platform that connects vacant properties, citizens and experts, and streamlines their efforts to reactivate buildings and optimise their public use by developing organisational, building and financial plans.

IHRB spoke with Jan Denoo, a partner at Endeavour.

Strategies and factors of success

“The city is transformative, rather than static”

The Locay platform facilitates citizen participation in city-led re-development processes, however, it is working to also facilitate community-led urban transformations. It will be able to receive proposals from citizens themselves regarding empty buildings, and open discussion of ideas for better uses of the space. Denoo highlights that success resides on the real need around a building. Locay can only trigger motivation up to a certain point, then the ‘community drive’ is what moves a project forward.

“A lot of people do not dare to dream this big about their city… you don’t think about buying a 10-million-euro tower, but when you think bigger scale: in terms of people, time and money, things become more realistic, you can stretch the mental window of what is possible.”

Challenges

Denoo points out to the need to strengthen the relationship with the city administration, and receive investment to develop the digital infrastructure of the platform. However, he states Locay needs a balance “to not become a service of the city, but stay a service for the citizens”. It is a constant challenge, since city government support is important, especially for large renovation projects, but Locay should remain independent so that it can serve civic and spatial needs that do not necessarily fit any policy framework at any time.

Looking ahead

Citizens can have a decisive role in city-making if given the right tools. It is a myth that participation processes are too slow or expensive. The right tools can speed up processes and yield more integrated and sustainable projects.

To deliver those tools, Locay is developing its sustainable financial model. The plan is to expand the platform to allow people to connect, communicate and share imaginaries for potential uses of vacant buildings; as well as offering a digital work space for citizens to log in to and work together in their plan.

Sofia Municipality, Bulgaria

Co-creating ‘healthy corridors’ with the action research project: URBINAT

The EU-funded action research Project URBINAT: Urban Innovative & Inclusive Nature fosters “healthy corridors as drivers of social housing neighbourhoods for the co-creation of social, environmental and marketable nature-based solutions”. The project is implemented in three front-runner cities: Sofia, Porto, and Nantes; and four follower cities: Siena, Nova Gorica, Brussels, and Høje-Taastrup.

IHRB spoke with Velin Kirov, the Project Co-Coordinator at Municipality of Sofia.

Strategies and factors of success

“Healthy Corridors” are urban interventions usually done in green linear public spaces that use nature-based solutions (NBS) to improve the space and mitigate climate risks. However, what is particular about this project is the wide understanding of NBS to also include human nature, and therefore include technological, territorial, participatory, and social and solidarity economy (SSE) solutions. See URBINAT’s NBS Catalogue.

“Healthy Corridors are viewed as a social and cultural infrastructure that has been co-created by citizens and stakeholders for the purpose of promoting the well-being of the community, and having a positive impact on health.”

Also, urban regenerations carried out include local communities throughout the whole process. This is done in four phases (1) co-diagnostic, an analysis of local conditions, needs and expectations; (2) co-design and ideation; (3) co-implementation/construction of the healthy corridor itself; and (4) co-monitoring the quality of the transformation.

A successful strategy in Sofia, has been the launch of the “Stakeholder Advisory Board” – a pilot initiative that has no parallels in the city. It gathers representatives of the local District Municipality, the URBINAT project, technicians, urbanists, academics, local NGOs, and concerned private citizens, in collaborative dialogue to make decisions about the project’s urban interventions.

Challenges

“We live in a representative democracy, but we are going through a crisis of this model… the relationship between representatives and citizens is damaged. We try to repair it by involving more people in the process, but that is not painless nor straightforward, it is an arena of conflict, it will trigger discontent and negativity. However, generating discussion in itself is the purpose of the exercise.”

What is particular about the URBINAT project is the effort to re-establish that connection between the administration and the public, while bringing positive social and environmental outcomes to historically underinvested neighbourhoods.

Legacy of the project

In Sofia, the “Stakeholder Advisory Board” can prove to be a successful model for a collaborative understanding not only for this project, but for all future urban interventions. The idea is to establish permanent boards for each city district.

The project is also creating horizontal networks of exchange and cooperation between different groups and fields of interests across the seven cities which “are crucial to the success of any kind of endeavour.”

“Each of us is a drop in the ocean, but if we are united by a common set of principles, by a common purpose, there is practically no limit to what we can achieve.”

UrbaSEN, Senegal

Towards a citizen’s movement in precarious neighbourhoods of the suburbs of Dakar

UrbaSEN is a Senegalese association that unites urban professionals and communities to work together on various urban challenges, including climate change. With the help of swiss NGO Urbamonde, UrbaSEN was created in 2012, from the need to support communities affected by many floods in the suburban areas of Dakar, Thiès and Louga. Nowadays, the association covers various topics including coastal erosion, flood prevention, urban regeneration, and creation of green public spaces.

IHRB spoke with Mr. Pape Ameth Keita, Head Coordinator and Ms. Magatte Diouf, Project Coordinator at UrbaSEN.

Strategies and factors of success

UrbaSEN’s main objective is to help vulnerable populations improve their living conditions. Through community engagement the association shows every member of the community has a role, a responsibility, and the capacity to dialogue with local authorities directly. UrbaSEN’s role is to:

- Support the emergence of organised community groups

- Provide technical assistance, advice and specialised services

- Aggregate and maximise the financial capacities of residents of precarious neighbourhoods

- Promote and manage urban programs and projects from a human rights perspective

“People freely become members of the federation without considering a specific project, but to be part of the community development fund. Projects vary and rotate in various neighbourhoods, so all can benefit. The incentive is solidarity and reciprocity.”

Challenges

With UrbaSEN’s financing mechanism, The Urban Citizen Rotative Fund (2014), community groups and donors chip in to a lending source to finance community projects. Funds are not tied to a specific project, but to community development in general. Its rotating mechanism allows to focus on some projects first, and then in others according to the fund’s reimbursement cycles.

However, the fund relies on the communities’ savings and international donors, without any financial support from the local or national government, nor from private companies. This on one hand, encourages people to act independently, but on the other, means there is an unexploited opportunity for financial support that could potentially make the fund larger and more impactful.

Read more about the rotating fund strategy here.

A bottom-up approach and the importance of saving

Ameth Keita highlighted that community-led projects have a huge potential, but need the right tools and support. This is a fine balance since UrbaSEN intention is not to be ‘a provider’, but rather to fill that gap with capacity building and by empowering residents to act independently.

“The key is to organise, train, and understand citizens have a role in the community, and a responsibility towards the others in the neighbourhood.”

Savings is also important:

“If you don’t save, you cannot solve your problem. You can have good ideas, but you are all the time running after donors, governments, and other organisations to finance what you want to do. It is easier to move forward with an existing fund.”

Cartagena Municipality, Colombia

How can all citizens participate in the formulation of a new Territorial Ordering Plan (POT)?

In Colombia, citizen participation in built environment projects is required and regulated by national law. The City of Cartagena de Indias has taken this principle of participation to the elaboration of its new ‘Territorial Ordering Plan’ (Plan de Ordenamiento Territorial or POT) to replace the 2004 outdated and expired plan.

A citywide participatory process carried out by Cartagena's Planning Office, included a co-diagnostic phase in 2020-2021 (with around 116 face-to-face and virtual contribution tables). The 2021-2022 co-formulation phase has three cycles. The first cycle included 65 in-person community workshops where residents were able to voice their needs and concerns for the new city’s plan. The next formulation cycles are currently in development.

IHRB spoke with Laura Victoria Arzayús, in charge of the design and implementation of citizen participation strategies for the new POT.

Strategies and factors of success: building trust

Cartagena is emerging from a period of political instability, having had 12 mayors in the last 10 years, due to various reasons, including cases of corruption. So, the current administration has placed great emphasis in building trust and making citizens feel heard.

A successful strategy has been to demonstrate outreach and presence in all the territory, especially in the most remote rural and insular areas – those traditionally neglected. Efforts include “characterization missions”: deployment of the City’s teams to remote areas to collect technical, economic, topographic information, as well as job expectations and social needs, through focus groups. This outreach has helped recognise and legitimise local communities' knowledge of their territory.

(SPN) “Desde mi perspectiva no es un idealismo, de verdad es lograble! y no es un esfuerzo adicional que estemos haciendo, es lo que se debe hacer para hacer el instrumento correctamente.”

(ENG) “From my perspective it is not an idealism, it is really achievable! and it is not an additional effort that we are making, it is what must be done to make the instrument correctly.”

Challenges

For participation processes outreach is always a challenge, especially for citywide complex processes such as this one. The Planning Department has provided as many and varied participation workshops as possible, and has a system to file, organise, and trace each individual contribution until its integration in the new POT.

“We cannot guarantee the citizens will in fact participate in this process, but what we can guarantee is to offer as many opportunities as possible to do so: in public and open, virtual and in-person spaces.”

The City Planning Department’s new approach

- Build trust by showing results

- Recognise people can be active agents by participating in these participatory processes and making their voice heard

- Acknowledge people are the primary source of information to guide the planning process

- Be transparent, inclusive and generating co-responsibility between the public sector and citizens

Citizens’ participation and co-creation creates ownership, which in turns allows sustainability.

See also a summary of a research and convening process on human rights and just transitions in Cartagena facilitated by IHRB and its sister organisation in Colombia CREER in 2022.

Tirana Municipality, Albania

What co-financing initiatives can help retrofit apartment blocks and make them more energy efficient?

In Albania, the residential building sector is responsible for 30% of the country’s energy consumption, and 60% of its electricity consumption. This means that improving the energy-efficiency of buildings is important to reduce the country’s contribution to climate change. To achieve this, the Municipality of Tirana developed a co-financing mechanism to enable energy-efficiency improvements to the city’s large residential blocks. The municipality has also worked to increase citizen engagement throughout the city as it expands access to green space.

IHRB spoke with Anuela Ristani, Deputy Mayor of the Municipality of Tirana.

Strategies and factors of success

The city of Tirana has many large cement Soviet-era residential buildings that are now old and energy-inefficient. The city identified the opportunity to renovate these buildings to make them more efficient while also improving their liveability. They also drew on lessons from past projects when they had learned that if the local community is not involved, projects have shorter lifespans. Conversely: with direct community involvement and investment projects have more chances of long-term success. The municipality established the Community Fund Initiative (50/50), a financing mechanism for the retrofit of these buildings: if a community organisation proposes an improvement project for their building or neighbourhood for which two thirds of the local residents are supportive, and the community can collect half of the funds, the city will provide the other half of funding, including support on the project execution and management. Under this initiative, 90% of projects relate to energy efficiency improvements.

The city has also acted to ensure that access to green spaces is expanded in all parts of the city, and that all neighbourhoods have channels for participation in city improvement initiatives, in order to reduce segregation and strengthen social inclusion. For example, the municipality has 27 physical offices, one in each neighbourhood of the city, uses a range of different consultation tools, and uses city schools as community gathering places.

“Urban development should always be in the service of communities…It is not just about spaces that look good, but about spaces that build strong communities: generations coming together, and building trust through sharing the same space.”

Challenges

One challenge with participatory improvement processes in the city, Ristani said, is that it is not possible to have everybody on board, so there is always some level of push-back and resistance. This is why it is important to engage and respond to the needs of as wide a range of city residents at possible.

Looking ahead

Ristani said that the next step is to adjust the balance where initiatives originate from. So that rather than the city reaching out to consult residents on specific projects, the dialogue should increasingly flow the other way, with residents submitting their ideas and proposals to the city on what it should be prioritising.

Just A Change, Portugal

Young volunteers renovating the rural homes of people living In poverty

Portugal has seen extensive migration from rural areas to cities. This has led to disinvestment in rural areas, where many individual and elderly residents feel isolated, and with some families in low-paying jobs living in poverty. Just a Change - whose motto is “Renovating Homes – Rebuilding Lives!” – works across the country establishing “Camp-In” projects through which volunteers retrofit and upgrade people’s homes. They partner with municipalities, local community members, and with the private sector and foundations who provide financial and in-kind support.

As Just a Change’s mission statement elaborates:

“…We rehabilitate houses without roofs, windows and doors. Houses where there is no hot water or electricity. We rehabilitate houses where it is cold all the time."

We rehabilitate homes because we believe that living conditions have a direct impact on reducing poverty and crime in the population. We rehabilitate homes because we know that it brings improvements to public health and energy efficiency in our country.”

IHRB spoke with Constança Vasconcelos Dias of Just a Change.

Strategies and factors of success

Just a Change has run projects renovating people’s homes in over 20 municipalities. Each intervention involves five main steps:

- Securing necessary financing from a combination of the municipality, private partners and foundations

- The municipality, together with local social organisations, provides a list of priority cases where residents urgently need their homes renovated

- Stakeholders are mobilised, including parishes, non-profits, local suppliers and contractors. As Vasconcelos Dias says: “usually, in the rural context, the community is very tight. As soon as neighbours, locals, small business owners see an intervention is being made to one of their own, they engage as much as possible, helping in the way they can.”

- The renovation itself, in which young volunteers from across the country and abroad work with the home owners/tenants and with technicians

- And follow-up, ensuring that the renovations are lasting and that relationships between volunteers, and between the volunteers and beneficiaries, are maintained.

Before

After

Challenges

One of the main challenges is the time that the process can take, to overcome bureaucratic obstacles. With municipalities where Just A Change has previously worked, the initiative is known and trusted and it is easy for them to return each year. For new municipalities, the set-up and planning stage takes longer.

Looking ahead

Vasconcelos Dias would like to see the Camp In projects evolve into a social business model franchise, so that they can be replicated across all municipalities in Portugal. Broad awareness-raising about housing poverty will also be important:

“Communities must be aware of the living conditions of their neighbours. We have found that, in Portugal, housing poverty is a very hidden kind of poverty, and people are often unaware of the living conditions of their next-door neighbour. Especially in urban areas. An effort must be done in spreading the message and showing proper numbers and side-effects of housing poverty.”

TRAZA Territorio, Spain

Using Multi-Stakeholder Engagement to Create a Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan (SUMP) for Hondarribia

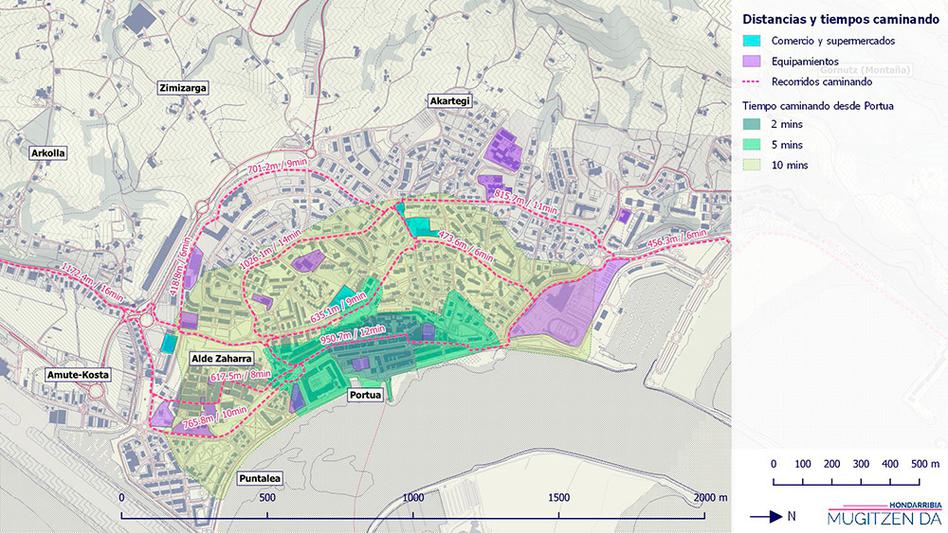

In 2018-19 the urban consultancy TRAZA Territorio together with two other firms – Gea21 and Biziker – coordinated a participatory process for the Municipality of Hondarribia in Basque Country, Spain, to create a sustainable urban mobility plan.

The project was initiated by the city’s “Mesa de la Movilidad Sostenible” (“Sustainable Mobility Roundtable”), consisting of the municipality and social organisations. It aimed to improve the environmental impact and inclusivity of the city’s transportation system, recognising that the majority of residents used cars to get around and that pedestrian and cycling pathways were in disrepair. The city has a designated website for sharing updates about the implementation of the plan.

IHRB spoke with Gonzalo Navarrete, partner at TRAZA Territorio.

Strategies and factors of success

Throughout 2018 the project engaged multiple stakeholders including social organisations, public institutions, economic actors and technical teams. Building off of the existing work by the Sustainable Mobility Roundtable, the process led a first round of participation, including training, interviews and public presentations. Then, followed diagnostic and visioning workshops, some only with local community members and others open to wider groups of participants: sessions were also held for specific audiences e.g. women and children. To strengthen the breadth of participation, the group sessions were complemented with in-depth individual interviews.

In addition to the plan itself, the process led to a) a shift in mind-set among the community members, political and technical stakeholders, towards greater awareness of the social and environmental dimensions of the transit system and the fact that things can be done differently, and b) a stronger network of people engaged in sustainable urban mobility.

Challenges

One of the key challenges is managing expectations, and ensuring follow-through and implementation of a plan, to avoid disillusionment. A deep participatory process can generate high expectations which then face economic and political barriers to implementation. This is why it was key to include political representatives within the process, as well as different city departments to coordinate the follow-up. While the implementation was slower than hoped, elements of the plan are now being put into place.

Looking ahead

A priority is to see the plan implementation leading to tangible improvements in accessibility, road safety and cleaner air. More widely, Navarrete elevated the fact that active involvement across broad groups of community members is important, given the social and cultural dimensions of the ecological transition: it is important to ground sustainability and equity initiatives in the context of people’s habits and lifestyles.