Air pollution – the human costs are too great to be ignored

15 June 2023

In 2010, I spoke at a conference on business and human rights to a corporate audience. At the end of my presentation, someone asked: “where’s the list of the human rights we need to consider?”

I responded, noting, the (soon to be) UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) made clear that the corporate responsibility to respect human rights applied to the full spectrum of rights contained in the International Bill of Human Rights and ILO Core Conventions.

I looked at their faces; they weren’t buying it. They just wanted a list.

While much progress has been made in the business and human rights field since 2010, including standards and tools to help companies carry out their own ongoing due diligence, corporate-related human rights abuses continue to persist.

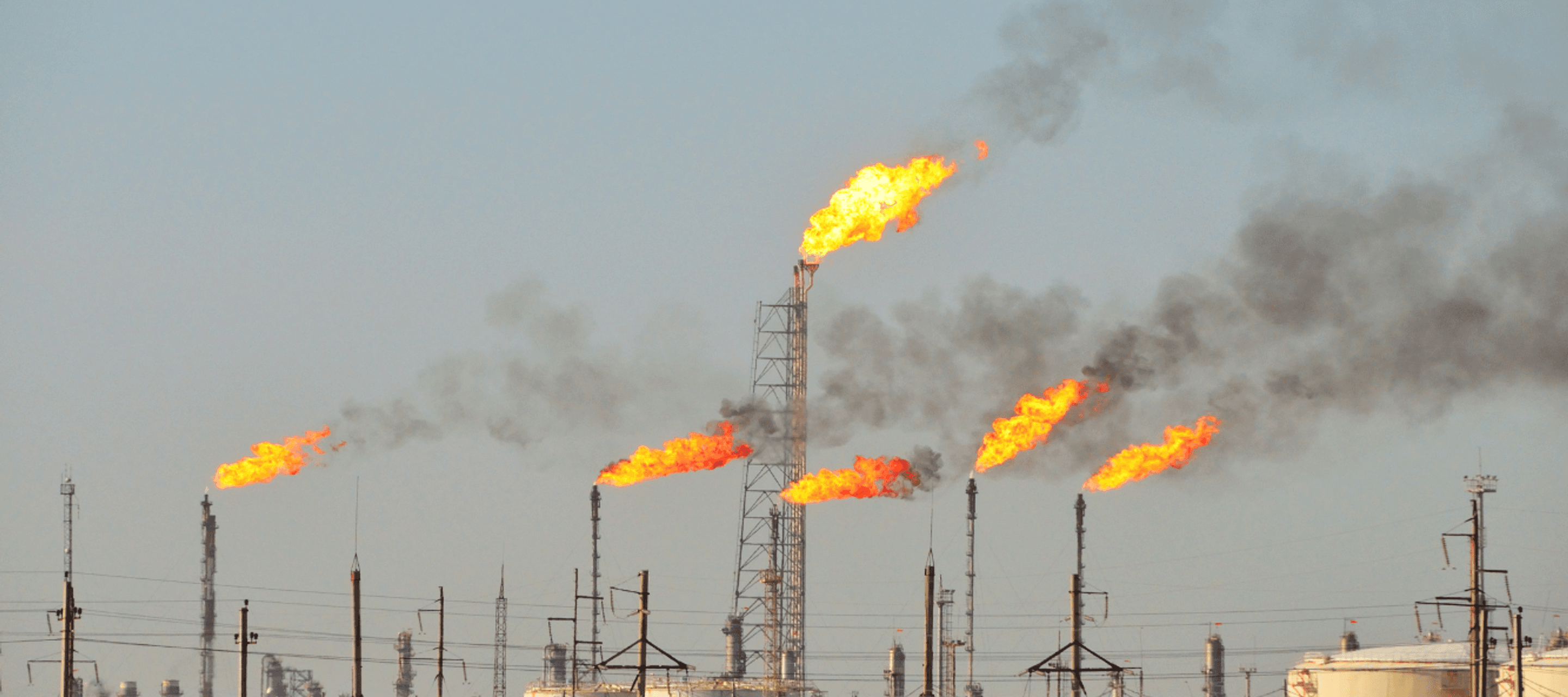

In one context, a company may address human rights risks systematically. In another, the same company may cause or contribute to abuses of fundamental rights. Consider corporate action on air pollution for example. Most oil companies have commitments to respecting human rights throughout their operations, yet the practice of gas flaring, which leads to significant harms, continues.

Gas flaring and human rights impacts

Gas flaring is the burning of natural gas associated with oil extraction. According to the World Bank, “flaring is a waste of a valuable natural resource that should either be used for productive purposes, such as generating power, or conserved.”

While the economic loss is immense, the human and environmental costs can be life-changing. In the process of flaring, carbon dioxide, methane, benzene and black carbon (soot) is emitted into the air. This combination accelerates global warming, but more immediate effects on human health can be seen in higher incidences of people contracting cancers and other health complications.

Gas flaring in Nigeria and Iraq

In Port Harcourt (Niger Delta), an area in Nigeria that has suffered for decades from intense gas flaring, a study in 2022 highlighted that birth defects were five times higher in the Niger Delta compared to the average in South East of Nigeria, and four times higher than the North East of the country.

While the practice persists in Nigeria despite international condemnation, over recent years, gas flaring in Iraq has captured international attention. Iraqi law forbids the flaring of gas within 10km of residential areas. However, satellite imagery shows flaring operating within a 5km range of residential areas in Rumaila, southern Iraq.

The impact of gas flaring on communities

In 2022, a BBC investigation called “Under Poisoned Skies” highlighted the daily toil and anguish of residents, including many children, living near gas flaring practices at BP oil fields in Rumaila, Iraq.

Raw footage and testimony unmasked the higher incidence of Iraqi children contracting leukaemia in the area, compared to other regions within Iraq.

Ali Hussein Juloon, who featured prominently during the documentary, was one such victim, contracting leukaemia in 2015, aged 15 years. Keen to show the world his reality, Ali videoed where he lived, his daily commute, including travelling to his nephew’s primary school. Intense gas flaring was clearly visible in the background.

Ali notes how his doctor, upon hearing he lives 2km from the gas flaring, diagnosed that the pollution from gas flaring likely caused his leukaemia. Given that gas flaring is known to emit benzene, a known carcinogen with higher-than-average links to leukaemia, this appears plausible. English history strengthens the plausibility argument. In the 18th century, many child chimney sweeps exposed to soot contracted scrotal cancer in large numbers. Given the direct professional aetiology, scrotal carcinoma became known as an occupational cancer of chimney sweeps.

Tragically, Ali died of leukaemia in April 2023, never receiving formal acknowledgement under BP’s Human Rights Policy, which states, “In line with this policy…, our grievance mechanisms include recording and reporting of grievances raised, including in relation to human rights, and actions taken to address them. 3.6.2.”

Approaching human rights due diligence

The UNGPs set out clear expectations for companies on human rights due diligence and respecting the rights of affected stakeholders. Central to this exercise is determining what remediating actions should be undertaken if any adverse human rights risks and impacts are identified. In this assessment, companies should consider the severity, and within that, the scope, scale and irremediability of their negative impacts.

While considering the scope and scale, it is critical to note that gas flaring emits high volumes of toxic pollutants into the air, therefore affecting large numbers of people. Scientific studies highlight that toxic pollutants such as benzene can cause, or at the very least, contribute to, higher incidences of cancers, specifically leukaemia, a life-threatening disease. The higher incidence of contracting a life-threatening disease, speaks ultimately to the lack of irremediability.

Corporate lawyers might say there is no definitive evidence that polluting emissions from gas flaring, causes, contributes to, or is even linked to the higher incidence of cancers in people living near oil fields. Indeed, evidence proving sole attribution is difficult to obtain and cancers are often caused by multiple factors.

While most oil companies are signed up to the UN Global Compact, which commits them under Principle 7* to support a precautionary approach to environmental challenges, and some have gone further to join the World Bank's Zero Flaring Initiative to end gas flaring by 2030, for those that do report against these standards, the human impacts associated with gas flaring has not been considered in their disclosures.

Time to consider other emissions beyond CO₂

Since the Paris Agreement, multinationals have turned attention to climate change; making declarations, setting targets, and in some instances, starting to address their Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions. In this race to Net Zero, corporates have myopically zoned in on assessing and addressing their carbon dioxide emissions, at the expense of their contributions to other polluting emissions.

For too long, air pollution has either evaded the attention of businesses entirely, or for many, it has been tackled as purely an environmental issue. However, the health harms associated with it can be immense and life-threatening. While governments are guided by the World Health Organization’s Air Quality Guidelines 2021, it is left to regional and national governments to impose expectations for business.

At the EU level, air pollution will soon be a disclosure requirement under the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive. As of 2022 in India, companies are now expected to report on air pollution management under the Business Responsibility and Sustainability Report requirement of the Securities and Exchange Board of India.

Yet, for companies not in these jurisdictions, they do not need to wait for government instruction to act on air pollution.

As the UNGPs state, businesses have a corporate responsibility to respect all human rights. The human costs associated with air pollution are too great to be ignored.

About the author: Désirée Abrahams is Senior Programme Manager in the Clean Air team at Global Action Plan.

* Principle 7 of the UN Global Compact is based on Principle 15 of the Rio Declaration, 1992, which states,: “where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation.”

Guest commentaries reflect the views of the author(s). See more.