2018 TIP Report: Despite Shortcomings, An Opportunity for Continued Advocacy in Southeast Asia

18 July 2018

The United States Department of State released its 2018 Trafficking in Persons (TIP) Report on 28th June, ranking 187 countries on their performance in preventing and addressing trafficking for labour and sexual exploitation.

The report was first published in 2001, following the adoption of the US Victims of Trafficking and Protection Act (TVPA), which sets out minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking both domestically and globally. The Act authorised the establishment of the State Department’s Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons and required countries receiving economic and/or security assistance from the US to report periodically on the measures taken to prevent and address trafficking. The legislation also authorises the US Executive to suspend certain kinds of assistance to countries failing to comply with minimum US standards against trafficking.

In Southeast Asia, the 2018 report’s ranking included a number of notable changes.

In Southeast Asia, the 2018 report’s ranking included a number of notable changes.

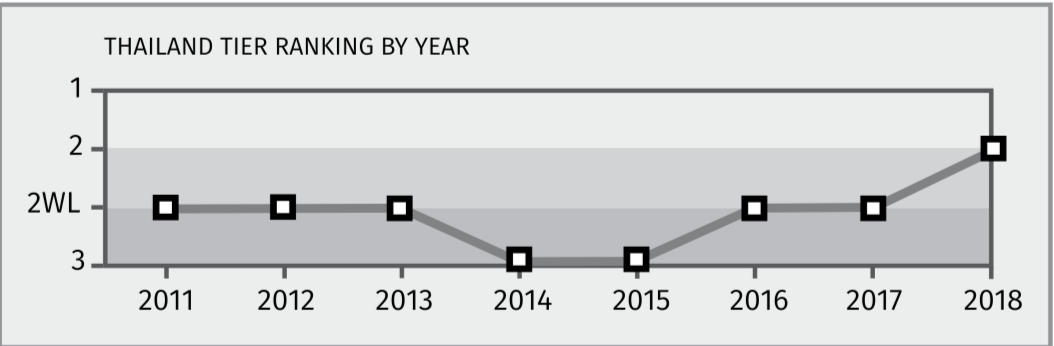

Thailand was upgraded to Tier 2, a category in the report applicable to countries whose governments do not fully meet minimum anti-trafficking standards, but are making significant efforts to do so.

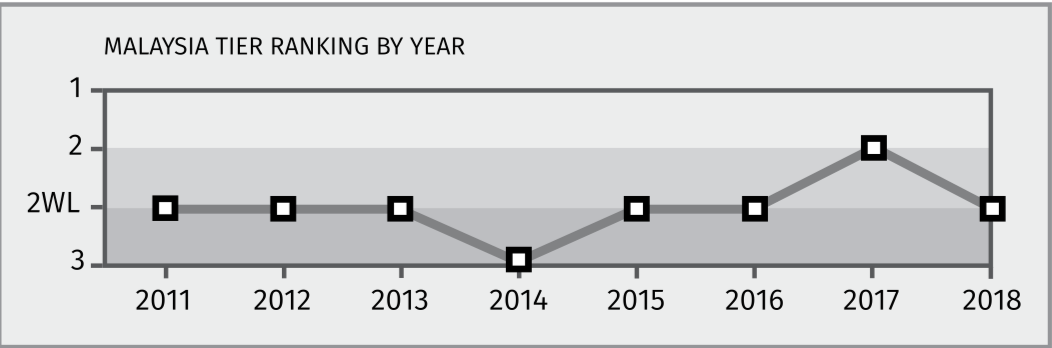

Malaysia was downgraded to the Tier 2 Watch List, which includes countries that require closer scrutiny, despite government efforts.

Two key migrant-sending countries in the region, Myanmar and Laos were downgraded to join the worst-performing countries in Tier 3.

Tier ranking: undermining credibility?

The upgrading of Thailand in particular sparked reactions from human rights groups, who claim that the move was unjustified in light of the country’s substandard performance in protecting vulnerable individuals and groups from exploitation.

Similar criticism emerged following the upgrading of Malaysia in 2015 and then subsequently in 2017, which was widely assumed to be a result of the negotiations for the original Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a trade agreement between 12 countries, including the United States and Malaysia, and which represented nearly 40 percent of global GDP before the US withdrawal in January 2017.

Critics of the report’s ranking system have repeatedly argued that while some of the tier placements reflect real progress or challenges on the ground, the overall inconsistency and politicised nature of country placements undermines the integrity and objectivity of the report, which the US Department of State defines as the “Government’s main diplomatic tool to engage foreign governments on human trafficking”.

In addition to its arguably political nature, the over-simplistic approach of the report’s three-tier system raises the question about its ability to assess extremely complex issues such as trafficking and forced labour, which can take forms ranging from debt bondage of migrant workers in Southeast Asia, to government-imposed forced labour in cotton harvests in Uzbekistan, to the exploitation of domestic workers in the Gulf.

A three-tier system (or four, if we include the Tier 2 Watch List), fails to capture heterogeneity within each rank and is likely to be viewed as a traffic light system, in which Tier 3 represents the worst-case scenario and Tier 1 indicates a modern slavery-free country, which is certainly unrealistic.

A three-tier system (or four, if we include the Tier 2 Watch List), fails to capture heterogeneity within each rank and is likely to be viewed as a traffic light system

Within the existing system, however, the TIP Report’s role as an advocacy tool and lever for accelerating progress is indisputable, and this should also be recognised.

In my own experience working with governments in Southeast Asia, I have encountered several high-level and technical government officials who were particularly concerned about how existing or proposed laws and policies could affect their country’s ranking in the report.

These concerns often trumped other considerations about the practical impact of laws and policies on the ground.

This raises the question of whether a single country and economic power assessing anti-trafficking efforts worldwide based on its own minimum standards jeopardizes other anti-trafficking initiatives, especially those focussing on internationally recognized standards.

It also highlights the importance of improving the report’s methodology and ranking system in order to ensure an impartial and objective analysis of countries’ law enforcement efforts, as well as their capacity to assist victims and to address risk factors increasing workers’ vulnerability to exploitation, such as unethical recruitment.

Acknowledging progress

While certain ranking upgrades may be viewed as unwarranted praise, the TIP report plays a crucial role in acknowledging countries’ efforts and encouraging governments to take further anti-trafficking measures.

In the case of Thailand, the government has intensified counter-trafficking efforts since allegations of widespread exploitation in the country’s fishing sector led to its downgrading to Tier 3 in 2014 and the issuing of a “yellow card” warning by the European Union in 2015.

In collaboration with international organisations and multi-stakeholder initiatives, the Thai government has introduced several measures to improve working conditions in the fishing industry and to strengthen law enforcement.

The country is also the first in Asia to ratify the ILO Forced Labour Protocol and is currently drafting a new Forced Labour Prevention Act to strengthen the existing anti-trafficking legislation, as well as a National Action Plan on Business and Human Rights, expected to be launched in September 2018.

[Thailand] is also the first in Asia to ratify the ILO Forced Labour Protocol and is currently drafting a new Forced Labour Prevention Act

It is undeniable that significant challenges remain, especially as the Thai government continues to use defamation legislation to prevent human rights defenders and migrant workers from reporting labour abuses and exploitation in certain industries.

However, for organisations such as IHRB who are working with business, civil society and other partners to advance responsible recruitment and migrant workers’ rights in Southeast Asia, the increased scrutiny stemming from the TIP Report, EU procedures, and international experts such as the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights can help highlight the need for ongoing advocacy in Thailand and the region as a whole.

As was evident from IHRB’s engagement with the Thai and Malaysian governments through Roundtable discussions we organised in partnership with The Consumer Goods Forum and in collaboration with the ILO and IOM in March 2018, recognising progress is essential in building mutual trust and encouraging dialogue between local governments and the private sector. Such joint action is also critical to identifying and promoting collective solutions to trafficking and labour exploitation.

recognising progress is essential in building mutual trust and encouraging dialogue between local governments and the private sector