Human Rights and the Built Environment - A Call for Action

22 July 2019

Two-thirds of humanity are projected to live in urban areas by 2050. If we are to make progress in reducing global inequality and in meeting the UN Sustainable Development Goals, a rights-based approach to the built environment is critical.

IHRB is launching a consultative process to develop and implement some core human rights-based principles across the built environment lifecycle, to advance collective action. These draft Principles for Dignity in the Built Environment and a programme of thematic research, collaboration, and advocacy are being developed in partnership with the Raoul Wallenberg Institute of Human Rights and Humanitarian Law, the Australian Human Rights Institute at the University of New South Wales, and Rafto Foundation for Human Rights.

Architecture has a defining influence over the character of the places where we live, work, and interact with others.

But first, what exactly are the issues these efforts are seeking to tackle?

What’s at Stake

There is a great deal at stake when we begin to look at different aspects of the built environment.

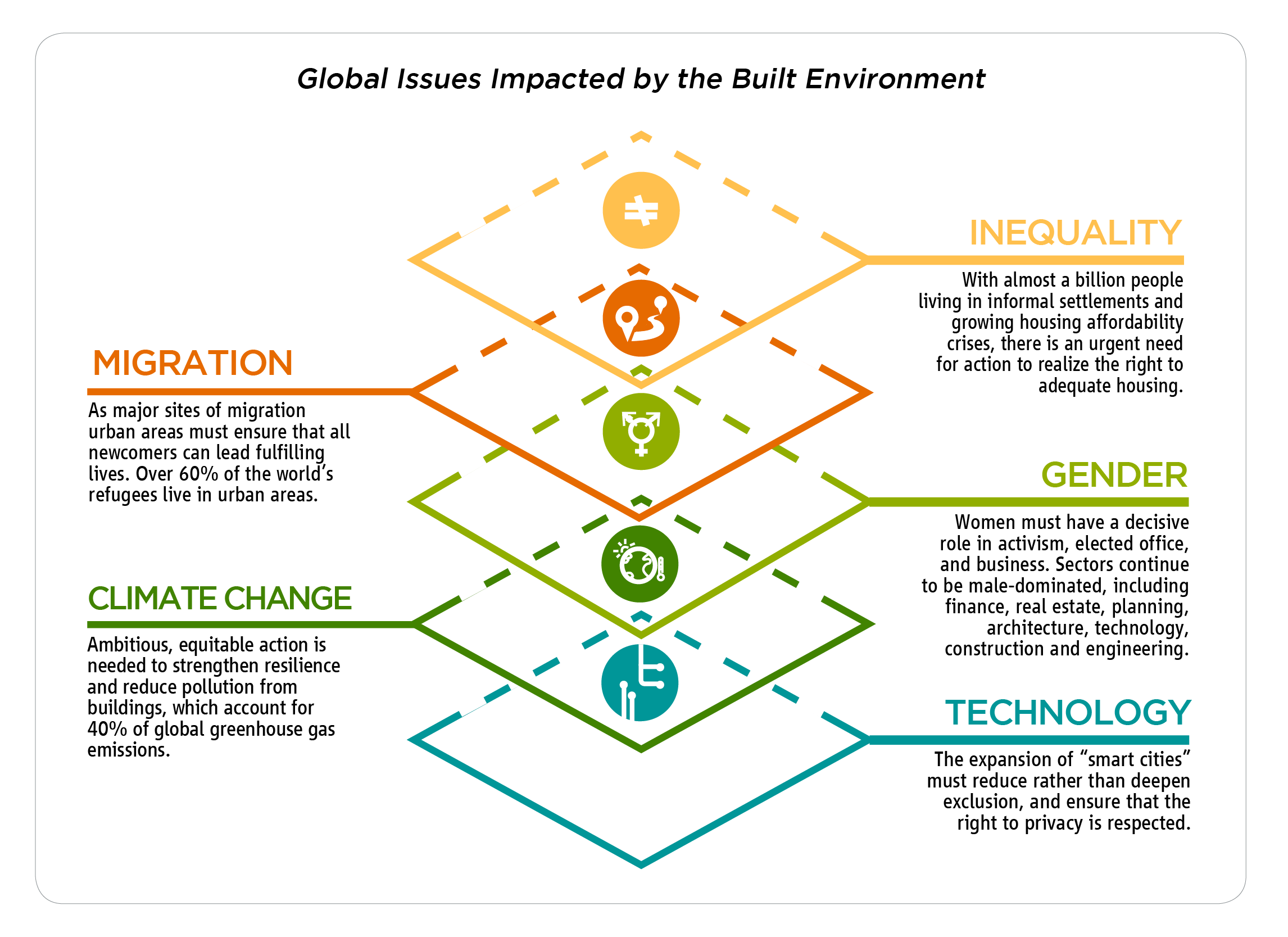

- Almost a billion people live in informal settlements, while in major financial centres residents face a growing affordability crisis as the cost of housing soars, exacerbated by its financialisation (the process by which financial institutions and markets increase in size and influence).

- Rising sea levels, increasing storms and extreme heat have taken thousands of lives and expose another aspect of the challenge. From Bangkok to New Orleans, climate change is bringing to light the stark divides between those able to retreat to safety and afford defences against a changing environment, and those, disproportionately women and children, who bear the brunt of these events.

- The global construction industry itself faces multiple human rights-related challenges. London’s Grenfell apartment fire, the Rana Plaza factory building collapse in Bangladesh, and the Odebrecht corruption scandal in Brazil are just some of the high profile examples – which reflect broader implications for human rights and inequality in the ways in which the places where we live and work are built and maintained. Meanwhile, a predominately migrant workforce in all regions frequently faces dangerous working conditions, meagre or even unpaid wages, and other forms of exploitation on construction sites.

- The rapidly growing role of technology in urban areas and rise of “smart cities” brings advances in connectivity and efficiency, but also risks of deepening exclusion, and widespread infringement of the right to privacy, particularly for minority and vulnerable groups.

The real estate industry alone represents almost 60% of global assets.

Power Players

The real estate industry alone represents almost 60% of global assets. The construction industry employs 7% of the world’s workforce. And architecture has a defining influence over the character of the places where we live, work, and interact with others.

All sectors in the built environment lifecycle can have adverse impacts on a wide range of rights – from the right to adequate housing to freedom from discrimination, from workers’ rights to the right to health.

Despite their potential impacts and ability to exert influence, for good or bad, these industries have received relatively little attention around their human rights responsibilities, unlike sectors such as mining, garments, and electronics.

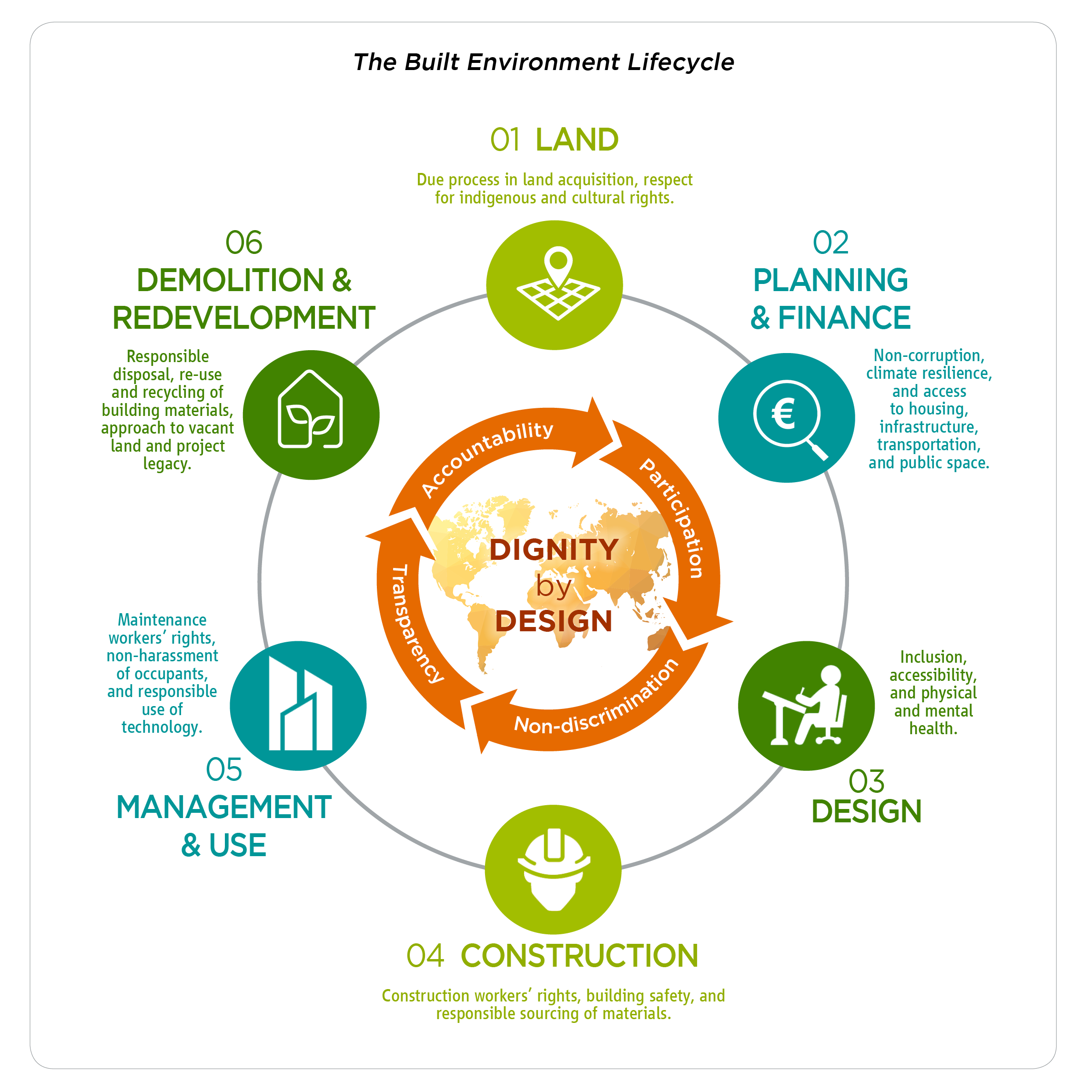

IHRB’s new report, Dignity by Design: Human Rights and the Built Environment Lifecycle, helps address that gap by highlighting the human rights issues and power relationships at each stage. The new report also provides a series of recommendations for action by the many actors involved.

Thoughtful and effective interventions must keep the rights of local populations at the forefront, and must break out of silos to address the connections between different parts of the lifecycle – from planning and finance, to design, to construction, to building maintenance and re-development.

The construction industry employs 7% of the world’s workforce.

In addition to national governments, municipal authorities have a critical role to play in enacting and enforcing laws to protect rights, and ensuring all residents can actively participate in decision-making that impacts their lives. Governments must take steps to ensure that the need to attract private financing does not stand in the way of investment in the public interest. In many instances, municipal governments are taking steps to advance human rights in areas where governments at the national level are falling short.

Architects can design buildings with the dignity and rights of users and broader communities in mind, while also engaging in planning and policy efforts that seek to address underlying inequality.

Construction and engineering firms can work to uphold labour standards throughout all tiers of their contracting chains, increase opportunities for women, uphold environmental and social standards in their procurement of materials, and ensure that buildings are structurally safe.

Technology firms can take concerted action to respect digital rights and ensure transparency, accountability and non-discrimination in the collection and use of data.

And as financing is critical at all stages of the lifecycle, investors should ensure their investments flow in ways that are closely aligned with locally-defined priorities, adding value not just to their own bottom line but also to the communities involved.

How Can We Mobilise?

Siloed, disconnected approaches will fail to address root problems or lead to long-term solutions. The draft Principles for Dignity in the Built Environmentseek to advance greater, effective interaction between stakeholders. They are applicable at the level of individual projects and in wider urban development, offering a vision for dignity and respect for human rights throughout the built environment lifecycle and recommendations for action: from land acquisition, planning and financing, through design, construction, management and use, to demolition and re-development.

The draft Principles are not a new set of standards. Instead, they are based on international human rights standards, and connect to existing initiatives.

The draft Principles are not a new set of standards. Instead, they are based on international human rights standards, and connect to existing initiatives, to provide a practical framework across each stage of the lifecycle.

IHRB, Rafto, University of New South Wales, and Raoul Wallenberg Institute will be consulting widely with stakeholders on the content of the draft Principles, to finalise them and inspire action to put them into practice.

For further information or questions on the draft Principles, or to share your feedback and expertise, contact annabel.short@ihrb.org. We are particularly interested to hear from stakeholders regarding:

- Content: Do the draft Principles adequately address what you see as the spectrum of human rights risks and responsibilities? Are there any obvious omissions? Any specific suggestions on wording?

- Application: In what practical ways are these Principles likely to be useful to you/your organisation?

- Spotlights: Do any of the human rights issues featured in the Principles stand out as being particularly important in your region / context – or in need of greater research?