Rights and Wrongs: Best Or Loudest?

27 November 2018

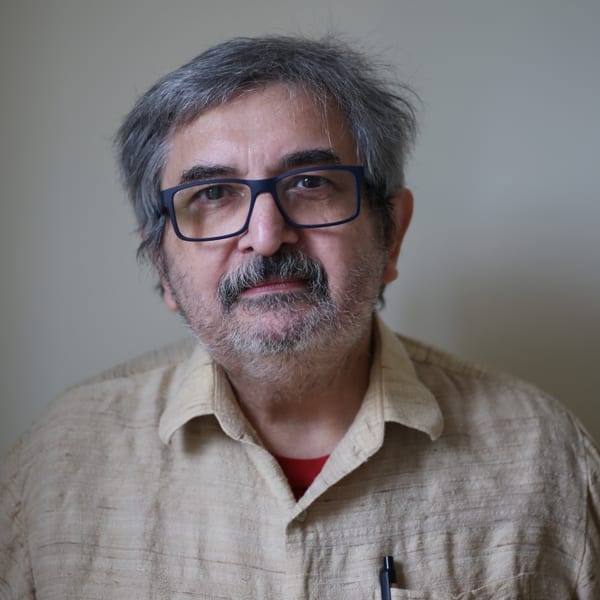

Last week, Jack Dorsey, the chief executive of Twitter, visited India. He met a few leading women activists and journalists who use the social media platform extensively, in order to understand better how they felt about the space his company provides for free expression.

Those who oppose the viewpoints of under-represented voices sometimes employing intimidating and vituperative language to drive out the vulnerable voices.

Like other Silicon Valley companies, Twitter is born out of a libertarian ethos, and believes in people’s right to express themselves freely. At its best, that means under-represented voices get the space to speak, which mainstream media and other fora often deny them. But free expression cuts both ways – it includes small cars and large trucks; and those who oppose the viewpoints of under-represented voices also use the same medium, sometimes employing intimidating and vituperative language to drive out the vulnerable voices. Instead of allowing many voices to flourish, Twitter is giving new meaning to Darwinian logic – the survival of the loudest, and sometimes the vilest and the rudest.

The Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen has called Indians ‘argumentative’, which they are; but anyone familiar with what passes for television talk shows in India would know that in practical terms it means he who shouts loudest gets his way. And that voice is usually male. Many Indian women have faced overt sexism, threats of sexual violence, exceptionally rude insults, and other forms of attack, with a view to drive them away from public platforms like Twitter. Indeed, some of such ‘trolling’ is organised, as Swati Chaturvedi, an award-winning journalist, documented in her book I Am A Troll. Barkha Dutt, a prominent broadcaster and Washington Post columnist, is among many women who have received abusive phone calls as a result of their decision to be heard on important issues.

Many Indian women have faced overt sexism and other forms of attack with a view to drive them away from public platforms like Twitter.

Other women journalists have faced threats of sexual violence. Rana Ayyub, an investigative reporter (and an award-winning journalist) found that someone had morphed a pornographic video, replacing the actor’s face with Ayyub’s, and released the video on social media. Most recently, Shehla Rashid, a doctoral candidate and student leader who has spiritedly campaigned for the right to dissent, found the atmosphere so toxic that she decided to quit Twitter altogether.

India is certainly not the only country where blatant misogyny gets wide reach online. But the problem is a real one, so it was understandable that Dorsey wanted to hear from Indian women about their experience on Twitter. At the meeting, Sanghapali Aruna, a Dalit activist, presented him with a poster that said Smash Brahminical Patriarchy. A photograph was taken that was subsequently released on Twitter, and all hell broke loose.

Twitter is giving new meaning to Darwinian logic – the survival of the loudest, and sometimes the vilest and the rudest.

Dorsey faced significant criticism from many Indians. Some called him a supporter of hate speech. Others, including a retired senior executive of an IT company who has invested in pro-government media in India, asked Twitter for a reaction to its senior-most executive aligning himself with what they described as a divisive slogan. A body claiming to represent Brahmins has filed a defamation suit against Dorsey.

The lawsuit is unlikely to go far – by any reckoning Brahmins are the privileged, dominant minority in India. They sit at the top of Hinduism’s complicated caste hierarchy, and even though they form less than five percent of India’s population, they nonetheless command vastly disproportionate resources, hold senior executive positions and have top jobs. Dalit activists challenging the hierarchy are calling for an end to that Brahminical patriarchy – the poster is not saying Brahmins are to be eliminated. By no stretch of imagination can the poster be termed ‘hate speech’.

And yet, a senior Twitter executive posted an apology, distancing the company from the message, and claiming that the photograph was private; the poster was given entirely at the initiative of the Dalit activist; and that the company did not intend to cause offence. That is a laughable explanation; for it would then imply that Twitter actually supports the reverse argument – that Brahminical patriarchy is a good thing. India has banned caste-based discrimination and there are in fact stiff laws to punish atrocities against the Dalits.

Companies have spoken out because it makes a compelling business and moral case, and upholds human rights standards.

In terms of messaging, the poster was the equivalent of a black South African giving an American corporate head a poster saying 'Smash Apartheid' during the 1980s in South Africa (or, in the same vein, someone in the US giving an executive a poster saying 'Black Lives Matter'). In each case, it is entirely possible that any progressive chief executive who understands the role of business in society would hold such a poster publicly, and align the company with those demanding protection of rights. Several US companies have, for example, challenged the Trump administration over the decision to restrict visitors from certain countries; or hired more refugees to defy restrictions being placed on the inflow of refugees. Some business leaders have criticised the US decision to walk away from the Paris Accord on climate and opposed the decision in North Carolina to prevent transgender people from using bathrooms that are appropriate to their identity. Companies have spoken out in these instances because it makes a compelling business and moral case, and upholds human rights standards.

Twitter’s apology is baffling. By distancing itself from a clearly political message, which affirmed the rights of Dalits and women who felt crowded out on Twitter, the company, in effect, legitimised the political orthodoxy, and those who believe in discrimination and attacks on women, including remarks intended to chill free speech and which threaten violence. Twitter should have instead joined the right side of the debate about the status of Dalits in India.

Social media companies rely on technology and algorithmic calculations to determine if a specific post is offensive.

To be sure, Twitter is not the only company facing such a predicament. Facebook too has a spotty record in understanding free expression and human rights. These companies rely on technology and algorithmic calculations to determine if a specific post is offensive, and if the right number of boxes are ticked, and sufficient number of people complain, then the account is likely to get placed under close watch and may get suspended. This has led to ridiculous outcomes such as rational Bangladeshi bloggers who challenge religious fundamentalism being suspended from Facebook. By acceding to the demands of concerted efforts of the powerful, social mediacompanies are undermining human rights defenders, activists, dissidents, and, indeed, anyone who uses these platformsto express their views openly. They too often end up bowing to the powerful, rather than giving voice to those without power. Without perhaps realising it, these actions perpetuate inequities and become part of the wider social and media establishment. And in this particular case, they embolden the misogynists and privileged, who are relentless in their opposition of those fighting for their rights and who happen to be women.

Their position is that they provide the space, but aren’t in charge of content. But each social media company sets its own rules.

Companies like Twitter and Facebook have refused to get drawn into any conversation about what people should be allowed to say and what they can’t. Their position is that they provide the space, but aren’t in charge of content. That would have made sense if the companies were offering a truly free-for-all environment. But of course they don’t. Each social media company has its own terms of service, and each sets its own rules, under which it decides to allow or ban specific content or accounts.

As a recent New York Times exposé of Facebook shows, senior executives considered banning President Trump over some of his remarks. They decided not to, because they were swayed (partly) by the free speech argument. They may also have been influenced by the potential backlash they might have faced from Trump’s many supporters. At the same time, Facebook did not hesitate in suspending the accounts of the Myanmar military, which had nearly 12 million followers (in a nation of 60 million people), particularly after credible evidence emerged that the army was using its postings to create an environment of hatred towards minorities, in particular Rohingyas. The United Nations has of course called for Myanmar’s military leaders to be charged for genocide.

Whether Facebook was right in allowing Trump to continue and banning the Myanmar army are interesting questions to ponder.What’s clear, however, is that companies have not set a reliable and credible framework to make these decisions. UN experts have called for them to adhere to international standards.

What’s clear is that companies have not set a reliable and credible framework to make decisions.

Companies have the responsibility to respect human rights – which means not only respecting the rights of those who express their views online, but also the rights of those who may face the consequences of remarks made on social media platforms.

This is not to suggest that Twitter and Facebook should become censors and take on the role of the state. But they should be held accountable by the same standards that apply to news media. That would require serious reorientation in the kind of thinking that has prevailed in Silicon Valley. Taking action is necessary if these companies wish to continue to claim to offer space to unrepresented voices, including women, and particularly women of colour or who are underprivileged.

Violence against women is often physical, but the chilling effect that the free-for-all atmosphere on social media has created has led many women to withdraw from the medium. That should be a matter of real concern for any conscientious executive keen to uphold all human rights.

This is not to suggest that Twitter and Facebook should become censors and take on the role of the state. But they should be held accountable by the same standards that apply to news media.

Dorsey was right when he upheld the banner that called for smashing the patriarchy privilege offers. His company was wrong in trying to distance itself from that stance.