Due Diligence and Fear

18 November 2014

John Morrison’s thoughtful and thought-provoking new book, The Social License: How to Keep Your Organization Legitimate, features many quotations from experts working at the intersection of business and human rights. One of the most compelling is from his colleague Salil Tripathi, who points out the reality that, “It is hard to measure the absence of a human rights abuse”.

Tripathi is referring to the need to peel back the layers of any indicator, such as the absence of demonstrations against a specific factory or other business operation, which some would like to think of as evidence that surrounding communities are content. Others might rightly ask, however, if the communities are too afraid to protest. The presence of fear is difficult to measure.

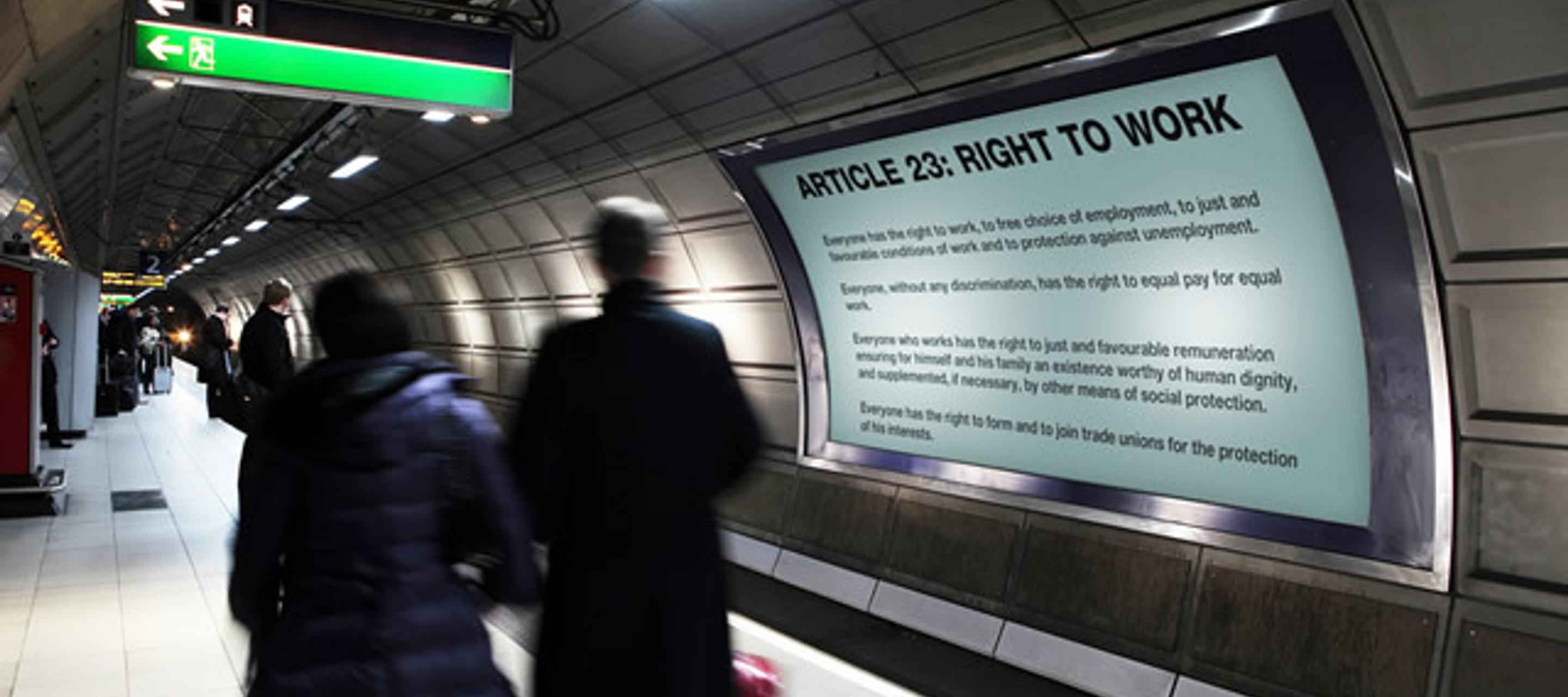

And no rights fit better into that “hard to measure” category than trade union rights. Article 23 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that everyone has the right to work, including the right to join and form trade unions. An essential element of trade union rights is freedom of association. The exercise of this and many freedoms is short-circuited by fear. Freedom of expression and freedom of association are among the most vulnerable rights. As Edmund Burke said:

“No passion so effectually robs the mind of all its powers of acting and reasoning as fear."

One of the fantasies too often propagated by traditional CSR was the “proof” through various social auditing methods that freedom of association was not being abused. Such claims were even furnished, in some cases, for work places in countries where freedom of association was banned by national law. Even when efforts were sincere, results were often distorted by worker fear of speaking out about their conditions and an imbalance of power between workers and employers that was not understood by those from outside undertaking the assessments who were unaffected by it and not sufficiently knowledgeable about local realities.

Trade union rights consist of freedom of association as well as the right to organise and the right to collective bargaining. Although these rights are obviously linked, they are different in terms of what business is expected to do to ensure they are respected in practice. Respect for freedom of association basically means “doing no harm”. Business should not interfere in any way with the exercise of that right or try to influence the decision of workers as to whether they have trade union representation.

Respect for the right to collective bargaining, on the other hand, requires active business engagement with the representatives of workers. The right to collective bargaining cannot exist for workers unless the employer is willing to negotiate in good faith. As stated in the publication on The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the human rights of workers to form or join trade unions and to bargain collectively (a due diligence guide issued by the ITUC, IndustriALL, UNI, and the Clean Clothes Campaign), “A business enterprise should not refuse any genuine opportunity to bargain collectively with workers even where it is not legally obligated to do so.”

A business seeking to respect as best as possible human rights in its own operations and with its business partners does not have to prove or measure, in Tripathi’s words, “the absence of a human rights abuse” at the risk of finding out that it is mistaken or of being “exposed” by others. The changed approach of the UN Protect, Respect, Remedy framework and UN Guiding Principles, as compared with traditional CSR, is a serious set of expectations and obligations linked to a practical means to ascertain impacts on human rights holders. This is summed up in the concept of human rights due diligence. The effective implementation of human rights due diligence throughout the enterprise is the best way for a business to improve respect for human rights. It is also a concrete process that can be evaluated with reporting on the risks encountered and the measures taken to address those risks.

Due diligence is not a matter of ticking boxes. It requires an intelligent and creative process to understand actual and potential impacts and put in place mechanisms to deal with them. It is too important a process to “leave to the Generals”. It must be part of the work of the operational parts of a business and subject to high expectations. The nature of human rights due diligence processes as set out in the Guiding Principles requires real analysis and an open attitude on the part of every business. Thought and reflection cannot be replaced by checklists or slick but empty reports.

Due diligence will not permit a business to measure human rights abuses, but it can help to prevent and address adverse impacts on human rights and, in doing so, may narrow that wide-open field where abuses will happen without a trace.

“Respect” can create a climate in an enterprise and with business partners that is neither positive nor neutral on human rights abuse, but is, rather, determined to identify and counter adverse impacts on human rights.