Healthy Cities, a Human right : IHRB’s contribution to the ISOCARP World Planning Congress

1 March 2023

From 3-6 October 2022, Alejandra Rivera from IHRB’s Built Environment Programme joined the 58th ISOCARP World Planning Congress in Brussels, Belgium. The Congress theme this year was “From Wealthy to Healthy Cities - Urbanism and Planning for the Well-Being of Citizens” and its main objective was to promote the “search of a new planning agenda for urban health, sociospatial justice and climate resilience” in cities. The event was organised by ISOCARP the International Society of City and Regional Planners, a “member-led global organisation with the vision of making cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable.”

With this objective on mind, the congress aimed to deconstruct the meaning of “healthy cities” and was therefore structured around four tracks: Healthy People, Healthy Planet, Healthy Governance, and Healthy Economy. This holistic approach allowed to explore in detail the different determinants of physical and mental well-being in cities. The presentations and discussions ignited dialogue, knowledge-exchange, and potential partnerships in the planning profession with the aim to advance an ecological transition that is socially and spatially just and healthy.

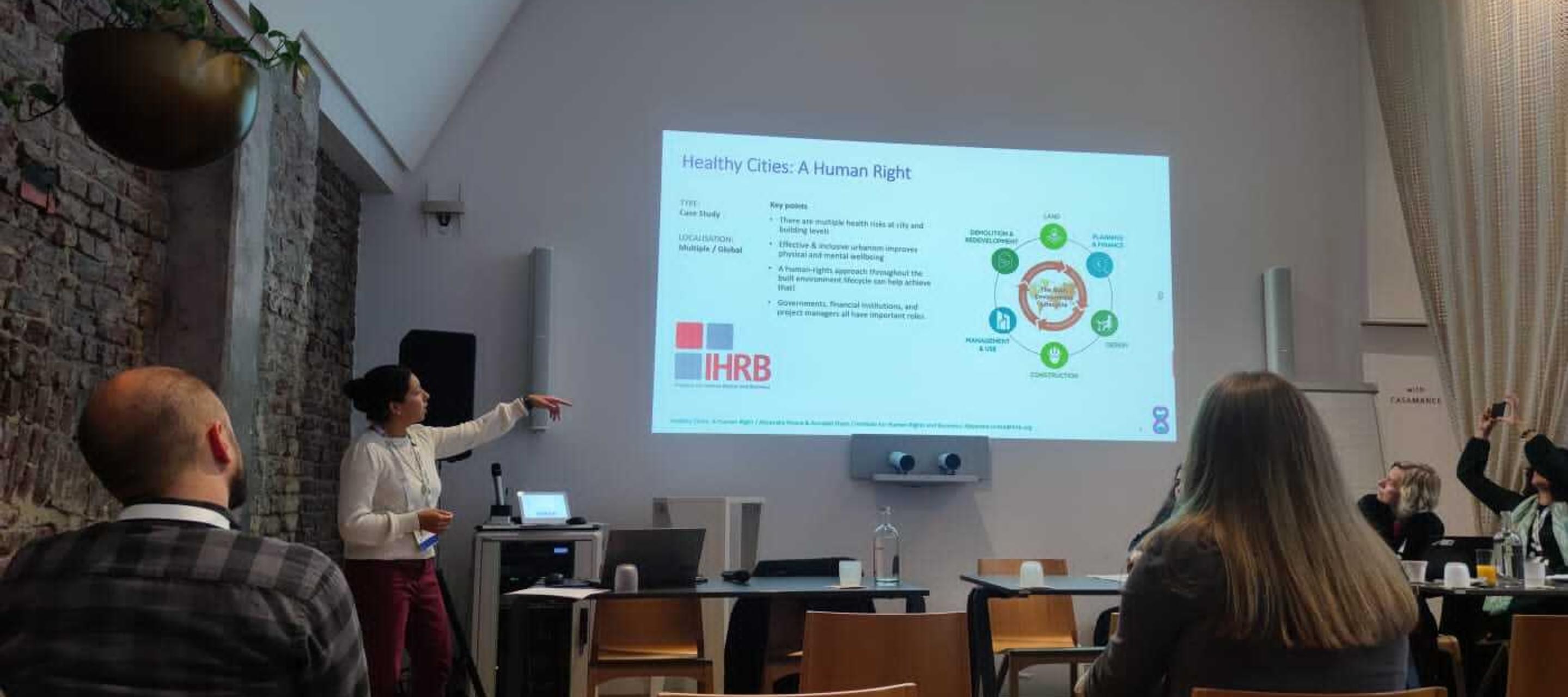

Alejandra’s presentation to the congress was titled "Healthy cities: a human right”. It showed how effective and inclusive urbanism can improve physical and mental wellbeing, and how adopting a human-rights approach throughout the built environment lifecycle can help achieve that.

Some key points from Alejandra’s 15-minute presentation were:

• Existing health risks at city level are: air pollution, Urban heat islands, anxiety and other mental health issues, and socio-spatial disparities in health risks. At building level there are risks like: household and ambient air pollution, poor-quality housing, toxic construction materials, density, and inadequate design to dwellers’ needs.

• Inaction will exacerbate these issues, but if harnessed, effective urbanism –planning and governance– can significantly improve the quality of life and wellbeing of people by reducing illnesses, and hence government expenditure, having a more productive and healthier workforce, reducing employee absenteeism, and overall having happier and healthier citizens

• Human rights approach from IHRB: the concrete and practical ‘Framework for Dignity in the Built Environment’ helps guide governments, investors, developers, project managers and advocates on specific social considerations for each stage of the process. With this tool they can minimise risks to human rights and maximise social outcomes, including the physical and mental well-being of people.

• There are several good examples that show how it is possible to plan, design, and build in an inclusive way and mindful of health needs. Some are: EU Horizon 2020 Project VARCITIES, New North Zealand Health Facility in Hillerød, Denmark; or the Psychopedagogical Medical Centre in Vic, Spain; among others.

• Key recommendations for:

Governments

• Align decarbonisation & physical and mental health strategies

• Channel finance to building retrofits of hospitals/medical centres

• Expand free and unconditional access to green public spaces

Financial Institutions

• Invest in companies with clean and circular construction approaches

• Invest in nature-based solutions

• Require portfolio companies adhere to WHO Housing and Health Guidelines

Project Managers

• Address health risks and opportunities through the ‘Dignity by Design Framework’

• Use evidence-based design

This presentation was a summary of an academic paper by the same name published in the conference proceedings. Read the full paper “Healthy Cities: A Human Right” here (pg. 718).

This paper and presentation are based on IHRB Built Environment Programme’s previous research conducted for the “Better Building(s)” 2021 report. In addition to the right to physical and mental health, other thematic focuses of this report are: the right to housing, nondiscrimination, participation, workers’ rights, and the role of technology.

Insights from the Congress:

The congress counted with an audience of urban and regional planners working for urban development, engineering and design companies, as well as public urban planning agencies and other government organisations; it included as well a mix of urban planning master and PhD students, and well-established professors from multiple sub-disciplines in urban studies. This worked as fertile ground for insightful discussions with inputs from various angles. Here are takeaways from four sessions:

Measuring well-being to increase the effectiveness of urban planning

A joint pilot project by Metropolis conducted in three cities:

Montreal has 51 Key Performance Indicators to measure well-being, and focuses on the subjective ones through a city-wide survey. In Barcelona, there is not such survey, so city officials rely on statistics of the determinants of health. In Brussels, they are trying to stay away from neighbourhood scores to avoid stigmatisation, but still use internal indicators to analyse the quality of the living environment.

Alejandra Rivera, from IHRB’s Built Environment Programme, was invited by the session organisers to provide feedback into these presentations. Her main take-aways were:

1. Progress on the discourse: It is a significant step forward to look for indicators beyond the GDP [to measure success], and aim to gain and measure a comprehensive understanding of well-being –factoring education, housing affordability and quality, social inclusion, employment, and urban design, etc.

2. Importance of resilience: City governments can be more resilient to external shocks, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, by: (a) Investing in basic urban systems and infrastructure; (b) constructing strong safety nets (data-driven, need-centred social programs); and (c) increasing their reaction time, facilitated by efficient urban governance structures and good, open communication with citizens.

3. Tools for healthier and more just cities: indicators –statistics, KPIs, and indexes– even the well-being ones, only show the symptoms. IHRB’s ‘Dignity by Design’ Framework can help implement projects and policies in the built environment that are more socially-conscious and aligned with well-being goals.

The energy transition of cities

This session was focused on the technical and economic aspects of the energy transition. The panellists discussed optimisation of energy production and storage, the increasing demand of heating and cooling with climate change, and how district heating networks harness the benefits of circular systems. There was less talk, however, about the socio-spatial distribution of those solutions. There are issues of energy poverty, ‘renovictions’, increasing energy prices, and the benefits of green-building certifications and district heating networks not reaching underserved peripheral areas, which should also be part of the conversation. (See IHRB’s report ‘Human Rights and the Decarbonisation of Buildings in Europe’ for more on these issues and recommendations to address them)

The debate is also about leadership. A representative from Engie, asked where are national governments setting the way for the transition? “if national policies would dictate, for example, to divert investments from gas to renewable energy, the private sector would [unhappily] have to comply”. While this is undeniable, on the other hand, companies themselves can also take lead, especially when the speed of change of technology and industry policies is much faster than national laws. Also, strong gas lobbies around Place du Luxembourg seeking to maintain the status quo is another reminder of the need to transcend economic interests for a just energy transition to happen. It is a matter of shared responsibility where each one has a role to play: the government to regulate, companies to shift their business models, and consumers to change behaviour, without waiting for the others to start.

Not-so obvious things with large impact

• DeAndra Navratil, on the Master Trails Plan from Greene County in Ohio, USA highlighted the importance of connecting physically key areas of the city, while also connecting people with nature. This trail network, the largest in the U.S., was a refugee during COVID-19, and also helps with road safety, accessibility, and economic benefits for small businesses around the trails.

• Siphokazi Rammile, from the University of the Free State in South Africa, made the audience reflect how names of streets, towns, places can have a direct impact on people’s mental health. Toponyms in South Africa have a clear link to racial segregation and socio-economic differences, and are a daily, constant reminder of such reality. She recommends a highlyparticipatory approach to these historic scars, not necessarily renaming, but using storytelling to embrace, understand, and overcome the past.

Women in planning

The issue is evident if the topic requires a dedicated session, and even more so, when the people showing up are only women. Simin Davoudi professor of Town Planning at Newcastle University, emphasised that planning is about inclusivity for all, not only women, but the elderly, children, disabled, men, and women. A key takeaway from this session is about the ‘added value of women’. Female planners tend to be more sensitive to social issues, human connections, safety and security in cities, perhaps due a maternal instinct to protect(?). Another form of women empowerment is to become aware and harness that added value for the planning profession: to think, plan, and design being sensitive to social issues, to ultimately yield more inclusive and just cities.