How should businesses respond to an age of conflict and uncertainty?

26 March 2024

As 2024 began, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen aptly summed up our deeply worrying collective moment. As she put it, speaking at the annual World Economic Forum in Switzerland, we are moving through “an era of conflict and confrontation, of fragmentation and fear.”

It does feel these days as though humanity is teetering on the edge.

Brutal conflicts, seen perhaps most prominently, but by no means exclusively, in Ukraine, and in Gaza and Israel, have claimed so many innocent lives. Armed violence and civil strife are tearing apart countries from Haiti to Myanmar to Sudan and beyond. Humanitarian emergencies continue to leave millions of people suffering in dire circumstances. In a year of elections around the world, even traditionally stable democracies face threats of political turmoil. These and many other crises, tragically, may seem inevitable today, given the absence of agreement on means to bring about human security for all.

An increasingly fractured world order raises serious challenges for the business and human rights agenda. As part of IHRB’s Circle of Innovators roundtable series, we recently brought together individuals representing a range of perspectives and experiences to take stock and consider ways forward. The focus of our day of discussion in Washington, DC was on the difficult choices business leaders must make in navigating conflict situations and changing global dynamics, specifically in the contexts of international finance, trade, and transitions to a green economy, as well as in the work to rebuild communities and nations facing and recovering from conflict.

The following reflections don’t attempt to summarise the rich dialogue and many insights we heard from participants, who included representatives from companies, governments, international institutions and civil society. The aim instead is to point to some of the complex and interconnected issues raised, and to offer some reminders of where committed individuals and organisations might turn to advance responsible business conduct in such troubled times.

Strengthening responsible finance amid geopolitical tensions

Institutions created after World War II as the foundations of international order, designed to promote shared prosperity and development, and guarantee global peace and security, are currently under enormous strain, and in need of significant reforms to meet evolving realities. Governments, and the multilateral system they established, are struggling to manage turbulence within nations, as well as new economic rivalries, heightened nationalism, and geopolitical tensions, especially as the climate crisis becomes ever more urgent. Added to this, commitments to investing in a sustainable future still aren’t being matched by anywhere near the resources and actions needed.

Financial institutions of all kinds, from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, to sovereign wealth funds, private banks and investors, play critical roles in promoting shared economic and social prosperity. They are all the more important when instability within and between countries is on the rise. International financial institutions have contributed in the past to the responsible business agenda, through frameworks such as the IFC’s Environmental and Social Sustainability Performance Standards and the banking industry’s Equator Principles. But real challenges remain in ensuring robust and widespread implementation, notably in conflict affected and high risk areas.

Meanwhile, newer financial actors such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank are being called on by human rights experts and civil society advocates to take their own responsibilities seriously. That includes prioritising meaningful engagement with affected communities, disclosing relevant information on project impacts, and putting in place effective grievance mechanisms, all in order to prevent or mitigate harms linked to their financing.

Many in the financial sector still don’t have in-depth knowledge of how their decisions may cause or contribute to human rights harms. This is compounded by the backlash to, competing visions of, and legal risks associated with, ESG investment models and policies. Adding to these problems is the current lack of acceptable data and metrics so that all companies share clear benchmarks for best practices on social performance issues.

Exercising ‘leverage’, as set out in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, continues to be an under-explored concept for many in the financial world, and governments remain largely unwilling to influence private financial actors’ decisions for the public good, in particular, when investing in fragile contexts. These and other stumbling blocks must be addressed urgently given the central role of finance in fostering peaceful societies, achieving sustainable development, and addressing the climate crisis.

Advancing trade that protects workers at risk

The international trading system also faces multiple challenges in today’s unstable environment. Disruptions linked to violence, sanctions, destruction of critical infrastructure, and suspension of transport routes have all played parts in undermining shared aims of global economic interdependence. At the same time, Covid-19 made plain that over reliance on any single company, country, or trade route carries significant risks. Responses to the pandemic, alongside heightened political tensions between major trading nations, such as China and the United States, have resulted in strategies associated with ‘decoupling’, ‘derisking’, and ‘reshoring’, through which major trading nations and companies search for more stable relationships, and greater economic security. Businesses must ensure that any adverse impacts associated with such changes in supply chain policies and practices are identified and addressed as part of broader corporate human rights due diligence processes.

As more governments turn increasingly to protectionist policies and strain political divisions, negotiations on trade issues such as agriculture, fisheries, and digital commerce remain blocked, as was seen at last month’s WTO Ministerial Conference in Abu Dhabi. What too often is left unspoken in this tumultuous period are the impacts rising protectionism and divisive trade politics have on vulnerable individuals and communities. Despite some efforts to include labour and environmental provisions in regional trade agreements, many of the workers who are critical to maintaining open trade around the world remain at serious risk.

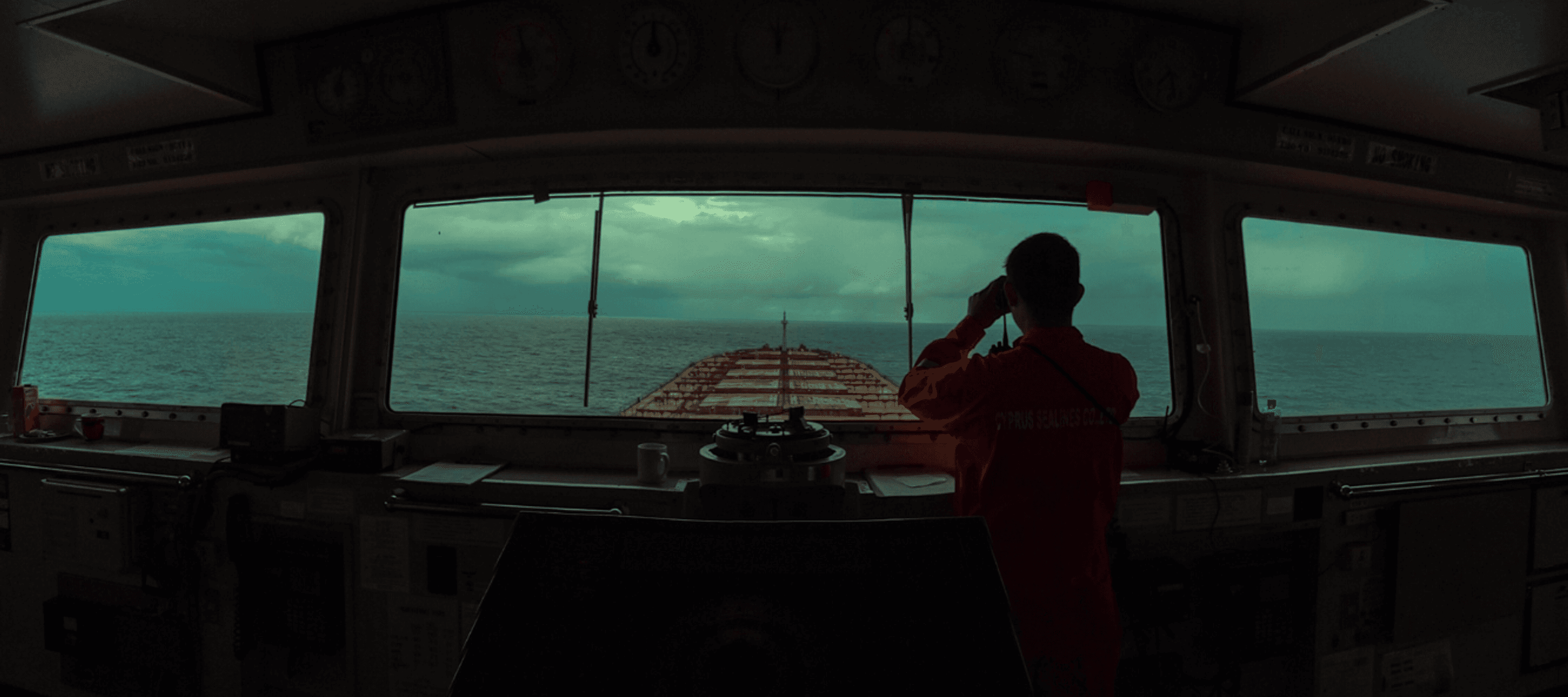

Among the most vulnerable are those in the shipping industry, seen in the precarious situations facing seafarers in many regions. Recent attacks on ships in the Red Sea by militant groups based in Yemen have not only threatened the lives of seafarers, but also resulted in widespread disruptions for the shipping industry, contributing to global fuel cost increases and shortages of food and other key goods. With an estimated 90% of all traded goods carried on oceans, shipping companies face difficult decisions on appropriate measures to avoid such attacks, or rerouting at significant costs. These actions have resulted in serious consequences for seafarers, their families, and communities, with no sign of the conflict abating. There is a clear duty on the part of governments, companies and other actors to address security concerns linked to trade, while recognising the importance of trade in preventing and rebuilding from conflict.

Preventing social disruptions in the green transition

Another area where conflict is playing out in specific business contexts is in the rush to transition to clean energy systems, driven by a diverse mix of renewables technologies. Achieving net zero carbon emissions by 2050 is an enormous challenge, requiring fundamental transformations in how humanity produces, consumes, and moves, locally and around the world. Over the coming years, renewable energy and infrastructure investments are required on a massive scale, but these transitions also come with significant risks to workers, communities, indigenous peoples, and vulnerable groups within societies.

The rapid pace of expanding renewable energy projects is already causing or contributing to disruption and dissent in a number of countries, and is raising alarm that growing conflicts of this kind, due to lack of community consent, or poorly planned actions by governments and companies involved, could become one of the biggest threats to fast and effective climate action.

Those involved in transition processes are recognising that social disruption and conflicts between governments, companies, and local communities can happen on multiple fronts, including over land ownership, during the mining of minerals needed for renewables technologies, as well in renewable infrastructure development and rollout. Conflicts of this kind are taking place in developing and developed countries alike, and mirror in many respects past experiences of hydrocarbon extractive operations. What began as local concerns over specific projects, in multiple cases later escalated to protests and serious security risks, with significant costs for individuals and communities as well as for companies themselves.

In the time ahead, renewables companies will need to learn the lessons of past experiences by other sectors in engaging with affected stakeholders in ways that can build social acceptance, shared visions, and equitable benefit sharing of clean energy systems. Companies in sectors that have developed policies and tools to guide meaningful stakeholder engagement should do more to help newer companies tackling similar challenges today. Stronger social and human rights assessments of projects will be critical, as will greater efforts to share knowledge and reflect the agency of and accountability to local communities, indigenous peoples, and environmental defenders in order to prevent conflicts that may slow or undermine critical transitions to a green economy.

Supporting recovery and reconstruction

The work of companies during and after conflicts to provide critical services, repair and rebuild roads, bridges, airports, hospitals as well as homes, schools, and factories, is an often under prioritised issue on the responsible business agenda. Private sector actors have unique abilities to mobilise the capital, expertise, and resources required to rebuild communities. But investments in essential services and infrastructure post-conflict in many cases haven’t adequately included critical elements, such as understanding local community contexts and needs, ensuring local level buy-in, capacity development and ownership of projects, and avoiding aid dependency by providing opportunities for employment for those recovering from violence or natural disasters.

In addition to investments in new and rehabilitated construction, there is a clear need to build institutional capacities and to combat corruption in such fragile contexts. Involving small and medium size enterprises, especially those committed to investments in sustainable building techniques, as well as women entrepreneurs, in reconstruction and economic development is also essential.

A number of new initiatives point in the right direction. A recently adopted model law on public-private partnerships and concessions, developed by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the UN Economic Commission for Europe, offers guidance to support governments, especially from emerging economies, in designing legal frameworks for such arrangements in ways that will help advance implementation of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. And a new “Environmental Compact for Ukraine” proposes a series of measures to enable reconstruction for a sustainable future based on accountability and recovery from the ongoing conflict.

There is understandably no single playbook for business in addressing the many challenges associated with conflict recovery and reconstruction. More must be done to align incentives and address imbalances in investments in such environments, especially aimed at promoting transparency and accountability for all actors involved in reconstruction efforts. As the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights has stressed, most reconstruction efforts will be based on contractual arrangements where heightened human rights due diligence should be required at all levels. Business leaders engaging in recovery and reconstruction work will need to demonstrate greater commitment to building back in ways that are rights-respecting and sustainable, and that foster resilient communities.

An ongoing challenge requires scaled up leadership

There is no doubt that many companies have and continue to make positive contributions to promoting more peaceful societies around the world. As just one example of how corporate leadership has made a positive difference in a crisis moment, the 2018 joint World Bank and UN report Pathways to Peace notes how the Kenya Private Sector Alliance, recognising the impacts of election-related violence in 2007-2008, worked with a number of civil society groups to help prevent recurrences in 2013.

Companies understand the importance of stable operating environments for their own long term success, and have played constructive roles over recent decades in addressing problems linked to conflict minerals, as well as challenges of operating responsibly in high risk environments through multi stakeholder initiatives and other forms of joint action. Today’s multiple conflicts and crises need more, not less, principled corporate engagement and leadership.

But it is also true that some in the private sector contribute to or benefit from conflict and uncertain geopolitical environments. Past and ongoing lawsuits demonstrate how companies have been complicit in human rights violations perpetrated by governments or armed groups. A recent ruling in a Dutch court ordering the Government not to export parts for a military aircraft to Israel, citing the risk of serious violations of international humanitarian law if used for airstrikes on Gaza, demonstrates the deep connections between business, trade and conflict that must continually be faced. Indeed, the newly adopted EU Directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence makes specific reference to business responsibilities in conflict-affected and high-risk areas, and points to where companies can find guidance by highlighting the 2022 UNDP guide on “Heightened Human Rights Due Diligence for Business in Conflict Affected Contexts” developed in collaboration with the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights.

In the end, today’s uncertainties and multiple conflicts demand that all companies continually assess their roles in societies, and be prepared to work with others to address shared challenges. This clearly isn’t an easy task, given that most operate in short-term time horizons, specifically when present in high risk environments, where responsible business practices may still not be considered a first priority for many actors. But the reality is that companies are rightly viewed around the world today as powerful actors that will play a huge role in shaping the way the future looks. No one expects business leaders to solve all political problems, or perform the functions of states. But we should recognise that this perilous moment requires a willingness to think again about what good corporate citizenship means, and how business can best support a more peaceful and prosperous world for all.