The perception of ‘value’ needs to change if the World Bank's mission is to succeed

26 April 2024

Last week we attended the Spring Meetings of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) in Washington, D.C. The annual IMF-World Bank meetings bring together finance ministers and central bankers from all regions as a platform for official deliberations on the global economy - from growth and inclusion, to financial stability, development, debt, and climate.

We each attended for different reasons: Vasuki as a long-time Fund-Bank watcher and a member of IHRB's International Advisory Council; Haley as head of IHRB’s Just Transitions programme, which engages all actors, including public and private financial institutions, on ensuring their net zero strategies are people-centred.

These institutions mark their 80th anniversaries in 2024 amidst ongoing calls for meaningful reforms that would make them better able to support emerging and developing nations in responding to climate shocks and extreme weather while also avoiding unsustainable servicing of previous debts. These are two key issues at the heart of whether net zero can be achieved at all, and in ensuring whole nations aren’t left behind in the process due to macroeconomic barriers.

So what were some of the key themes coming out of last week’s discussions, and why are they important for just transitions in particular?

Resilience Amidst Divergence

At the highest macro level, the IMF’s main message on the health of the global economy is best summed up in the headline of the semi-annual World Economic Outlook: “Steady but Slow Resilience Amid Divergence”.

The Fund’s main message reassured many investors: global growth is pegged at 3.2% this year and next. U.S. growth for 2024 is projected at 2.7%, quite an accomplishment for an advanced country with peers in Europe and elsewhere trailing far behind. With China’s growth downgraded to below 5% for 2024 and 2025, and with other emerging markets like Brazil and South Africa slated to underperform, India retains the bragging right as the fastest growing economy in the G20.

Despite the somewhat rosy picture of slow but steady resilience, IMF economists continue to worry about the pace of inflation (still high), the need for countries to rebuild fiscal balances, and the risks from growing “geoeconomic fragmentation” and the surge in “trade restrictive and industrial policy measures”. In other words, rich nations are currently much more focused on restoring growth and resilience in their own economies, creating divergence on and limiting the potential for consensus on macroeconomic and financial stability globally. Multilateralism is still alive it seems, but last week looked tired and fatigued.

The Great Reversal

While macroeconomic and financial stability issues took centre stage at the IMF meetings, the World Bank sought to focus attention on the plight of low-income countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. In a report titled “The Great Reversal”, the Bank declared that “one half of the world’s most vulnerable 75 countries are facing a widening income gap with the wealthiest economies for the first time in 75 years”. In other words, the period of great convergence in growth outcomes between rich and poor countries for the last three decades has come to an end. Not a promising start for the net zero transition to be a once-in-a-generation opportunity to eradicate poverty and generate leapfrog development outcomes.

The Bank rolled out other sobering statistics. One out of three poor countries are poorer on average than on the eve of the COVID-19 pandemic. More to the point, half of these countries are either in debt distress or at a high risk of it. Despite protestations and warnings from the Bank, poor country debt issues were discussed at the margin of the meetings – a dramatic reversal compared with previous years where it was one of the main agenda items.

The Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable (GSDR), established by the previous G20 Chair (India) and convened by the IMF and the World Bank, brings together public and private sector participants, including finance ministers from creditor and debtor nations. The GSDR did meet on the side-lines but a readout of the meeting was overwhelmingly procedural and technical. For example, the GSDR is worried about differentiated approaches by certain creditors (read China) between private and public debt, affecting the goal of comparability of treatment (CoT) (ie that all creditors should be treated similarly). The fact that CoT remains a sticking point four years after the pandemic demonstrates the lack of consensus within the G20 on how to resolve outstanding debt restructuring issues.

In addition to affecting general macroeconomic and financial stability, the issue of debt also strongly affects countries’ abilities to respond to the climate crisis.

Climate Chasms

It is no exaggeration that the IMF/World Bank meetings have become as important as the COP process in advancing climate finance issues (particularly given the UNFCCC’s financial crisis leading to the recent cancellation of regional climate weeks this year due to lack of funding).

At least $1 trillion a year is estimated as needed to help developing countries adapt to hotter temperatures and rising seas, build out clean energy projects, and cope with climate disasters.

Last week’s meetings witnessed a surge in climate finance-related discussions on the official agenda and in private gatherings. The role of climate sherpas (Ministers’ personal representatives) was to lobby the multilateral institutions for greater access to capital for middle and low-income countries (as well as greater forbearance on budget deficit targets). Likewise, there was much talk, as always, about the role of blended finance (how to strategically use development finance and philanthropic funds to mobilise private capital flows to emerging markets), though with few concrete examples of actual momentum in transactions.

The current reality is that while some money has become available over the last year or so to address climate impacts, the sweeping reforms needed are not yet forthcoming. While overhauling 80-year-old, highly complex, and large institutions is no doubt challenging, the truth is that the governments funding these institutions aren’t allocating the necessary sums for climate action to the countries hit hardest. The numbers are not reflecting the progress needed.

Hopes for the private sector to swoop in to fill these financial gaps are not materialising either. Banks and institutional investors remain wary of spending too much money on climate projects in the developing world, which are perpetually perceived and classed as too financially “risky”. And the money on offer is in fact going to rich and developed nations, who are seeing an increase in climate investments, while many poorer countries are missing out.

Looking ahead

Most observers point to growing momentum over the past two years towards agreement on critical reforms of these international financial institutions . Policymakers and economists gathered in Barbados and hashed out an ambitious reform agenda. The president of the World Bank stepped down after coming under fire for not doing enough to address climate change, and was replaced by an executive who promised to embrace this agenda. President Emmanuel Macron of France, hosted a summit aimed at building momentum for the work ahead.

But as of this 80th anniversary of the Bretton Woods Institutions, there is still a wide gap on both emerging and developing economy debt levels as well as the investments required to drive climate action at scale. In the same vein, it has long been recognised that the two institutions’ pro-growth predilections often overshadow human rights concerns, with preference given to investment-friendly projects despite inadequate measures to respect the rights of workers, indigenous peoples, and local communities.

Beautiful and bountiful policies for all these issues exist on official institutional letterhead but robust implementation on the ground is still absent in many cases – this was the summation in most of the discussions we sat in.

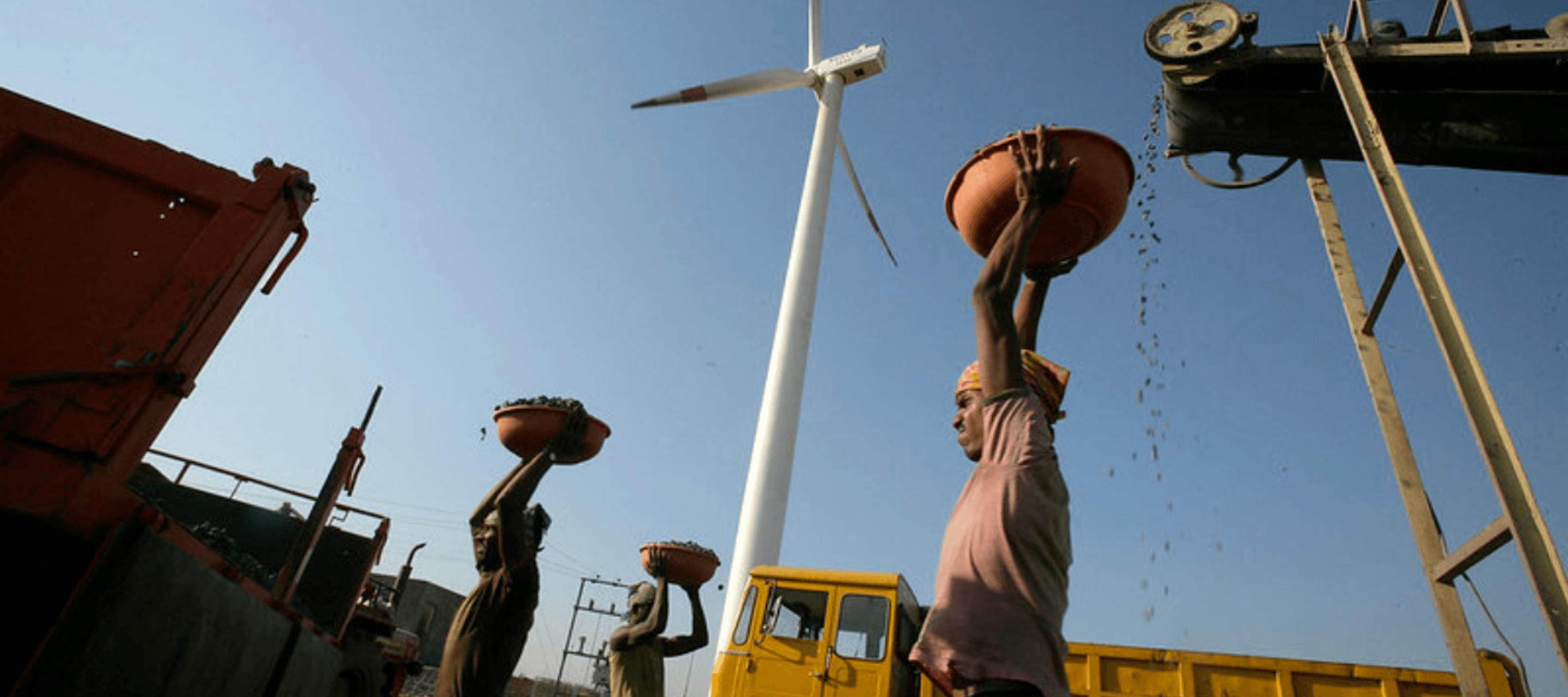

It is likely this implementation gap will be made more acute as 2030 climate targets march ever closer and the urgency and scale of climate action required continues to increase. Overcoming these challenges cannot be achieved by any individual institution acting alone. Governments and the private sector must step up, and in particular adjust their long-held perceptions around the value (rather than cost or risk) of investing in local enterprises, their workers, and communities. Because surely, they are at the heart of the World Bank’s new mission statement: to end extreme poverty and boost shared prosperity on a liveable planet.