Three criticisms of human rights that should be challenged

9 December 2023

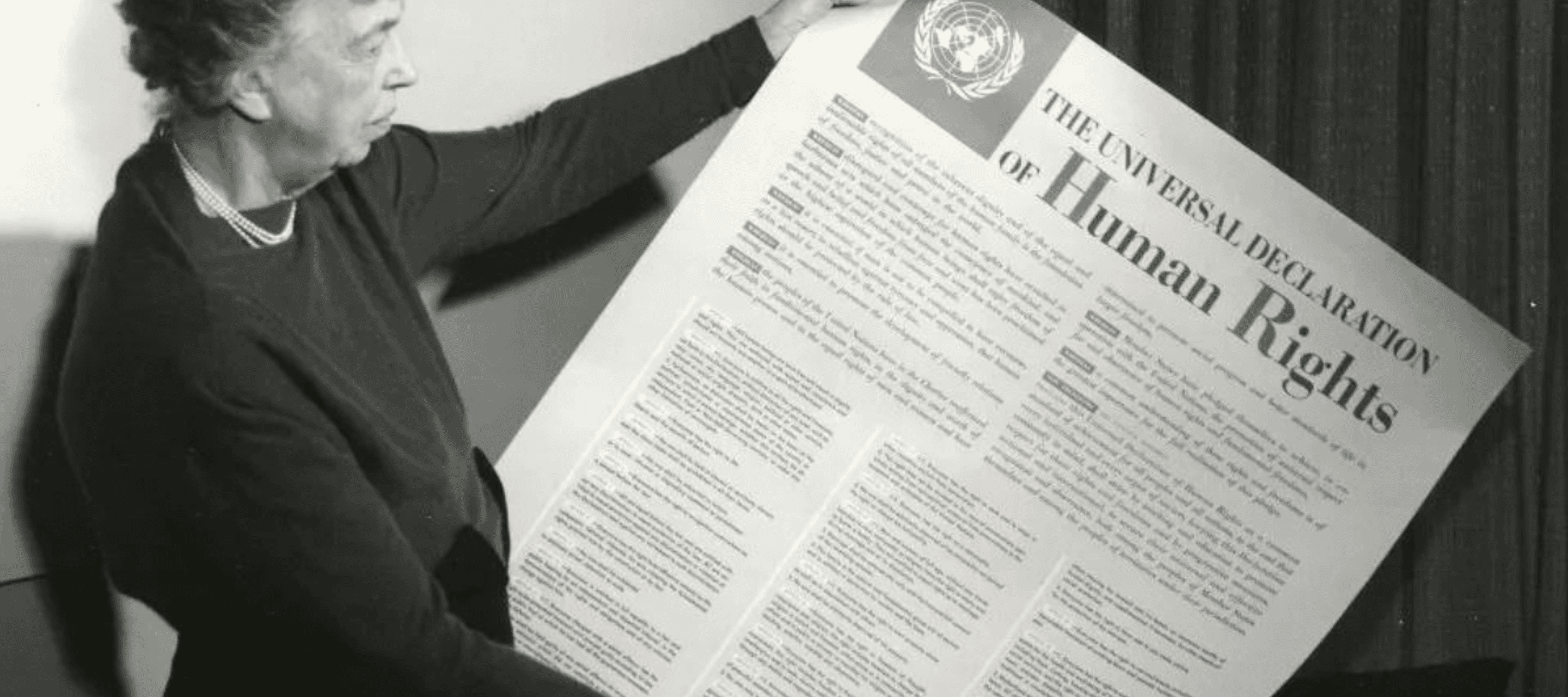

75 years ago, Eleanor Roosevelt and the other members of the drafting committee presented the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) to the still very young United Nations meeting in war-torn Europe at the Palais de Chaillot in Paris.

Human rights existed before this date but not in an all-encompassing form or as a bedrock for the international laws that would then follow. For what it is worth, signing the Declaration has been the price of membership of UN ever since. We are paying our respects in New York tomorrow and ask what a 75th birthday party means in our world riven with conflict and fragmentation? Below are three of the most common criticisms of human rights and reasons given for not to be celebrating anything at all. Obviously, I disagree.

"Human Rights mean little when millions are suffering today"

The current conflict between Israel and the Palestinians in Gaza, with humanitarian devastation and alleged war crimes, lead many to raise again the dark truth of the past three-quarter century, that human rights are still being abused with impunity. Think also of genocides in Cambodia and Rwanda, exterminations in Bosnia, Myanmar, Syria, Iraq, Syria and now Ukraine - to name but a few. Billions have had their human rights abused and millions have been slaughtered by their fellow men (yes, it is usually men). Human rights have not prevented death and suffering but they have provided the language for our collective outrage and sometimes, just sometimes, have helped to hold those responsible accountable years later. They have perhaps added to our "moral imagination" - the juxtaposition between the ethical claim that everyone "is born equal in dignity and rights" with the reality that this is far from being the case. When hostages and prisoner exchanges seem to put a higher premium on the life of one nationality above another, we have the grounds to ask why this is the case. Perhaps even the feeling that the world is full of double-standards, and the reality that the UN is largely toothless to protect human lives when its Security Council is divided, speaks to the fact that human rights (despite being so young in the history of the world) have earned their place at humanity's blood-soaked table.

"Human rights were imposed on the rest of the world by the victorious powers at the end of the Second World War"

Another criticism is that human rights mean little today for people in the Global South as they did not have a seat at the table between 1945-48 when the UDHR was written. It is true that 75 years ago much of the Global South was still under colonial control or too marginalised to have a voice. But the reality of those three years is a lot more complex. Whilst the UDHR can be seen as being in part a legacy of Franklin D. Roosevelt's "Four Freedoms" speech of 1941 (work continued by his widow after his death in 1945), neither Stalin or Churchill could be accused of 'self-interest' when reluctantly acceding to concept of universal rights. Human rights were not an entrenchment of power, in the way the permanent seats on the Security Council were. The revelations of the true extent and depth of the horrors of the Nazi regime, and in particular the holocaust, clearly mobilised western public opinion. But drafters such as Hansa Mehta of India stood for the anti-colonial demands of much of the world, which the Soviet Union liked to be associated with, and which countered the self-interest of the colonial powers such as the UK and France.

Those who think that that the UDHR is an imposition on some peoples values and cultures should also read the writings of two other key drafters: Charles Malik and Peng-Chun Chang. Whilst the process could undoubtedly have been more inclusive, particularly in terms of the voice of women, marginalised communities, and minorities, the UDHR goes a long way to reflect different philosophies and traditions. Human Rights sit uneasily with those who prefer utilitarian or populist approaches to the world’s problems. Spend some time at the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva today (the body which some US Presidents decide the USA should not even sit on) to hear the major powers of the world bemoaning why activists and other nations should be involving themselves in the 'internal affairs' of how they treat their own people. Let’s not forget - and Rene Cassin representing France on the drafting committee clearly did not back then - that the extermination of jews, gypsies and homosexuals by the Nazi regime was also an 'internal affair'.

The criticism of UDHR as being a ‘western imposition’ is but a part truth. Somebody had to impose it, as power is never given to the people through choice – and the UDHR whilst only declaratory in form, has immense moral power. Some of the criticism we hear today reflects as much on the cultural relativism, fundamentalisms, and conspiracy theories of today as it does the realpolitik of post-war consensus. Most authoritarian leaders, included those elected in western democracies, would love to wish away and wash away the UDHR and constantly do whatever they can to weaken its authority.

“Human rights have little to offer future generations”

Perhaps the most serious set of criticisms, in my view, are those that attack the UDHR, the International Bill of Rights and all the treaties that flow from them as being impotent, and perhaps even counterproductive, in meeting the existential challenges of today. It is a limitation of human rights that they say nothing of the rights of those who came before and those yet to be born. The threats posed by climate change, biodiversity loss, degradation of the environment, generative AI, nuclear war and so on are all intergenerational. How do the rights of future generations figure in the decisions we make today? How much human agency and autonomy need to be surrendered for the fundamental economic, societal and technological transitions required to meet these challenges? When we are told that only AI can meet the accountability challenges of AI itself, then there is clearly a set of concerns we need to work through.

It is likely that over the next 75 years, human rights will be abused not just by brutal leaders, greedy businesses or dogmatic zealots but also by the machines they employ, and eventually perhaps by the machines themselves without direct human control. Our event tomorrow in New York asks if Eleanor Roosevelt’s words about human rights needing to matter in “all the small spaces” on the farm, in the factory and in the office translates to the new spaces and places of tomorrow? Human rights are currently fighting to find a voice in climate negotiations as those of us at COP28 can attest to. They might be in the preamble to the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, but governments will find reasons not to include them explicitly in mechanisms relating to ‘Loss and Damage’ and the ‘Just Transition’.

We hear from some governments that it is extending human rights to minority X that has ‘broken the camel’s back’ and denied human rights their reference in ‘paragraph Y’ of some new agreement. But we know from the history of the last 75 years, that there is always an inconvenient minority that can provide such governments with the convenient excuse they need to keep human rights on a back seat. If it is not the LGBTI+ community that threatens the cultural sensitives of some nations, we are told, then it is their own indigenous peoples, women, young people, some religious minority or other, atheists, asylum-seekers… the list goes on. In fact, it does not take much moral imagination to understand we are all on such a list somewhere, we would all be an inconvenient minority to someone.

15 years ago, I helped to organise a 60th anniversary event in the Palais de Chaillot in Paris (the original venue) and still have the scars to prove it. This time we will be in New York and the Ford Foundation has currently leant us something a little more modern. No one would write the UDHR in precisely the way it was written in 1948 today. If humanity still exists in 2098, seventy-five years hence, then I am sure that the 150-year-old original will seem even more out of date in some ways. But any attempt at a rewrite now would be sure to fail and unravel quickly given the lack of any global consensus on almost anything these days. For its time, and perhaps for all time, it is an amazing document. It is the most translated text in human history, and it is the ongoing translation into the lives of the young that remains our ongoing priority.