Top Ten Business and Human Rights Issues in 2013

1 January 2013

To mark International Human Rights Day, IHRB has published its annual list of the Top 10 Business & Human Rights Issues for the forthcoming year.

Note: These ten issues are not ranked in order of importance.

Embedding respect for human rights across all business relationships

Growing awareness of the human rights impacts of business relationship activities will command greater attention on the corporate responsibility agenda over the coming year. Images of children stitching footballs and women bent over sewing machines for long hours have previously spurred attention to the question of the responsibility of businesses for what happens in their value chains.

But until recently, public focus has rested almost exclusively on human rights impacts in supply chains. Yet supply chain relationships are only one part of the larger web of business relationships that can be seen today.

The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights have put the full range of business relationships squarely on the agenda for companies around the world. The Guiding Principles make it clear that the responsibility to respect human rights extends to managing adverse human rights impacts through business relationships and provide guidance on how to prevent and address those impacts.

While attention to human rights in business relationships currently covers only a tiny fraction of the huge range of daily interactions between companies of every size, in all sectors and locations, those have the potential to become a key avenue for spreading awareness and implementation of the responsibility to respect human rights in the years ahead.

A new joint report by the Institute for Human Rights and Business and the Global Business Initiative on Human Rights titled “State of Play – The Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights in Business Relationships” explores the steps that a small number of large multinational companies are currently taking to begin to embed attention to human rights in a wider range of relationships, including but also going beyond supply chain – to relationships such as franchising and licensing, joint ventures and mergers and acquisitions.

Over the next five years, an increasingly wider set of relationships will command greater attention from governments, business, civil society, trade unions and consumers as attention to human rights in business relationships continues to deepen and widen.

Expanding action to combat forced labour and human trafficking

Efforts to combat human trafficking and forced labour will continue to play a growing role on the agenda for responsible business during 2013. The California Transparency Act and a new US executive order strengthening protections against trafficking in US public procurement will further focus attention on exploitation and abuse in company supply chains.

As part of their responsibility to respect human rights, companies must be prepared to ensure the safety and dignity of all those who make their products or provide services to the business. Increased scrutiny on companies which fail to undertake effective due diligence on their supplier factories or other areas of operations, which fail to take action on exploitative conditions, low pay and a callous disregard for a workforce in many parts of the world, will continually pose reputational risk for companies and sanction by government, shareholders and consumers.

Exploitation and debt bondage in supply chains are increasingly being highlighted as forced labour. Trafficking of workers into formal supply chains is still prevalent in some countries and industries, called out by US President Obama in September 2012 as “modern day slavery”.

Companies must also take more responsibility for their recruitment channels for labour to combat the risks of debt bondage, forced labour and trafficking. Migrant and temporary agency workers are a ubiquitous feature of many supply chains. These workers are particularly vulnerable to exploitation and abuse, and exploitation can be found at every stage of the recruitment process. In particular, enormous recruitment fees, often paid back at usurious rates of interest, render them effectively bonded labour before they even commence work, whatever the subsequent conditions of employment.

The Dhaka Principles for Migration with Dignity devised by IHRB in consultation with a range of stakeholders offer a framework for business to address the specific challenges of migrant workers from recruitment - through employment – to return.

Tackling challenges of dual-use internet-based technologies that may undermine privacy rights and freedom of expression

In the past year, international scrutiny of companies in the Information and Communications Technology (ICT) sector has increased in part because of revelations that several companies had provided surveillance technology to governments which undermined the rights of privacy and freedom of expression. While some companies actively marketed such technologies, others have struggled with the dilemma of supplying technology, which can have ‘dual-‘ and ‘multiple-use’.

The right of freedom of expression is not absolute, and governments have an obligation to protect people, for example from terrorism acts, for which courts recognise the state’s right to impose lawful intercepts.

Some companies in the ICT sector are required to maintain close relationships with governments and law enforcement agencies to provide the means for ‘lawful interception’ of communications in order to fight certain crimes. But some companies sell and market surveillance technology which may violate international human rights standards, such as mass intercept technology and ‘password sniffing’ software. These tools enable states to persecute human rights defenders, journalists, trade unionists, and other vulnerable groups, violating privacy and casting a ‘chilling effect’ on freedom of expression.

As the means to communicate digitally increase, a growing number of technology products originally intended to improve services and maintain the flow of data can also be used to scan private communications (such as deep packet inspection) and the means to enable lawful interception can be misused by states intent on controlling and suppressing their citizens.

This year, the European Parliament endorsed a proposal of MEP Marietje Schaake which called on the EU to “stop the export of dual-use items and technologies that are used as tools of repression through (mass) censorship, (mass) surveillance, tracing and tracking of human rights defenders, journalists, activists and dissidents.”

In order to avoid being accused of being complicit in the potential human rights violations that dual-use technology facilitates, companies in the ICT sector will want to be even more proactive in 2013 and beyond to prevent and mitigate such risks.

Advancing uptake of the UN Guiding Principles in key enabling sectors including finance, ICT and infrastructure

The past year saw growing awareness of the instrumental nature of key business sectors in ensuring respect for human rights. Best understood is the role project finance plays in this area – whether in the form of publicly provided finance (such as through the International Finance Corporation) or private provided finance.

In 2011, the revised IFC Performance Standards with strengthened human rights measures were a significant step forward in further, visibly embedding human rights into finance. 2012 has seen corresponding activity to align the related guidelines for OECD export credit agencies in the OECD’s Common Approaches for Officially Supported Export Credits and Environmental and Social Due Diligence and the ‘Equator Principles’ initiative of major private banks with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

Many aspects of finance – such as other dimensions of corporate finance or personal finance –have yet to fully address the UN Guiding Principles but should be higher on the radar screen in 2013 because finance is crucial to unlocking potential for development in so many sectors. Mainstream investment continues to be a mostly “human rights-free zone”, with the exceptions of Socially-Responsible Investors and those adhering to codes such as the Principles for Responsible Investment. Sovereign Wealth Funds also have significant impacts. The Government Pension Fund of Norway is now the largest stockowner in Europe and is increasingly conscious of its own responsibility to respect and ability to promote human rights. Its policies may influence the direction of similar actors in this area.

Another key enabling sector is Information and Communication Technology (ICT). ICT technology can facilitate freedom of expression as well as aid in realising the right to information, freedom of association and assembly. Equally important, technology is increasingly a platform through which many other rights can be enjoyed. The challenge for 2013 and beyond is to address the dilemmas such as those relating to internet technology as discussed in issue 3 of the 2013 Top 10 list (LINK). This includes addressing negative aspects of greater online access, especially in societies such as Myanmar (Burma) where the internet and greater political freedoms have led to growing hate speech and violence directed against the Muslim minority community.

Finally, infrastructure development will likely receive greater attention from a human rights perspective during 2013. The coverage, quality and accessibility of infrastructure networks have a direct bearing on the economy, the environment, and the quality of life of everyone. “Mega projects” for global sporting events that involve massive infrastructure work have sparked a wider interest in addressing the sector from a rights perspective during the years ahead, given the potentially wide range of impacts. The Olympics, FIFA World Cup and Commonwealth Games, will continue to face scrutiny around displacement, forced evictions, security, and the wages and working conditions of construction workers, in the run up to the Brazil FIFA World Cup 2014 and 2016 Olympics and Qatar’s preparations for the 2022 FIFA World Cup.

Leveraging government as an economic actor through public procurement policies that ensure respect for human rights

Creating coherence between human rights policy commitments and procurement is a well-recognised challenge for companies around the world. As the new joint report by IHRB and GBI on respect for human rights in business relationships points out, procurement departments are often incentivised to select business partners who offer the lowest price, and do not necessarily take account of their company’s own sustainability requirements, including its human rights policies.

Similar challenges can be seen in public procurement policies. Some governments are using procurement incentives and disincentives to encourage companies to promote human rights and sustainability in their value chains. For example, The Netherlands incorporates ILO core conventions and human rights standards into the social criteria for its procurement requirements.

The US government recently announced forthcoming changes in its federal procurement regulations to strengthen protections against trafficking in persons in federal contracts.

At the global level, a new report by the UN Secretary-General on the role of the UN system in implementing the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights also addresses the procurement challenge. It points out that under the UN sustainable public procurement initiative, guidance has been developed for procurers in the organizations of the United Nations system. The Secretary-General recommends further efforts to integrate human rights risk management into procurement and appropriate processes for addressing any risks identified.

Despite these examples, it is still unclear how most governments and international organizations weight human rights factors alongside price in final award decisions. This is a clear area of work for governments in advancing their "duty to protect"' human rights under Pillar I of the UN Guiding Principles. What seems certain, however, is that in the coming years companies that have human rights due diligence systems in place will be in a better position to respond than companies that do not.

Renewing efforts to protect lives in the work-place

Factory fires over recent months in Pakistan (with at least 262 deaths in a much publicized Karachi incident) and Bangladesh (with at least 124 deaths in the November Dhaka fire) – are painful reminders that workplace rights continue to be violated on a massive scale, including in factories supplying international brands.

2013 will likely see renewed efforts to address these abuses, including a major rethink of existing multi-stakeholder and CSR models that rely heavily on private auditing. Approaches to supply chains that focus heavily on compliance but ignore many of the drivers that incentivise low margins, low wages and poor working conditions will come under increasing scrutiny.

The ILO/IFC Better Work programme has tried to develop a more systemic approach to improving conditions of work by including government agencies and labour inspectors alongside private companies and trade unions. However, significant capacity challenges remain. What can be done to ensure that the drive for the lowest price does not come at the expense of human dignity and fundamental rights?

The coming year will also see greater attention to working conditions in a wider range of industry sectors. In February 2012, Auret Van Heerden of the Fair Labour Association (FLA) greeted the news of Apple’s FLA membership with a metaphor: “A proverbial ‘light bulb’ has gone off in the minds of consumers and corporate executives alike - no brand is immune to supply chain issues, and the abuse of workers will not be tolerated in any industry."

In its August 2012 verification report of Foxconn (the world’s largest producer of electronic components), FLA found significant challenges in meeting international standards. All eyes will be on the new Chinese Government in 2013 and the degree to which workplace rights take priority.

All these issues highlight the ongoing importance of the International Labour Organization (ILO), and point to some of the challenges for Guy Ryder as its new Director-General. Those that lay claim to verifying the application of ILO core labour standards must do so with integrity and never at the expense of strengthening government capacities in countries carrying the weight of global, as well as domestic, supply chains.

Mitigating the ‘resource curse’ by preventing negative human rights impacts of oil and gas exploration

How can countries blessed by nature but too often cursed by human nature, best ensure that exploitation of oil, gas, minerals and other resources benefit all their people and not just a few? One answer involves greater focus on potential human rights impacts, starting with the earliest stages of the resource cycle: those of pre-exploration and exploration.

Recent discoveries of oil and gas in East Africa: namely Tanzania, Uganda and (most recently) Kenya highlight the many national and regional dimensions to be addressed in developing resources in a way that benefits the entire population – starting with the most vulnerable.

Exploration licenses are not only granted to major oil companies but also a range of junior companies, some established for the purpose of gaining the license in question. These small exploration companies are therefore often without more developed policies and procedures around human rights due diligence, grievance-mechanisms or community consultation and as such can create social risks early in the project life cycle that have ramifications for the remainder of the project.

The governments of countries where large and small exploration companies are registered have a responsibility to be clear about their expectations related to national businesses as part of the first pillar of the UN ‘Protect, Respect, Remedy’ framework on business and human rights. That includes strengthening attention to human rights in the tools governments have for working with business in the sector such as export credit, trade missions and OECD national contact points.

At the regional level, mega infrastructure projects, such as the proposed Lamu Port South Sudan Ethiopia Transport Corridor Project (LAPSSET), will potentially transform several countries. LAPSSET is expected to provide a port, road, rail and oil pipeline connection between Kenya’s coast and South Sudan, Ethiopia (and possibly) Uganda. The human rights question here is at an even more strategic level. How can the potential impacts of such projects be understood and addressed before contracts are signed or commitments made? What can be learned from similar investments in other countries?

Moving beyond Africa, indigenous peoples living within the Arctic Circle are aware that exploitation of minerals, and potentially oil and gas, will significantly impact their lives. The same is true in other countries with emerging extractive sectors such as Mongolia, Kazakhstan or Myanmar – anywhere where minerals, rare earth metals as well as hydrocarbons are abundant. In the years ahead, we are likely to see greater attention to human rights due diligence in host government and bilateral agreements negotiated to secure national revenue as well as security of supply for investing governments and companies.

Linking respect for human rights to calls for greater transparency in lobbying by businesses

Lobbying has long been recognised as a legitimate tool for companies and other societal actors who seek to have their voices heard in public policy debates. In recent years, debates have grown around the extent to which ethical principles and greater transparency in lobbying are necessary for the purpose of protecting the broader public interest and safeguarding corporate reputations and legitimacy.

A number of tools have been developed to support these efforts such as the UN Global Compact’s “Towards Responsible Lobbying” report.

These initiatives have come in response to criticisms that corporate commitments to respecting human rights have not been consistent with industry lobbying efforts in some areas. During 2012, the issue was raised by Global Witness in the context of alleged discrepancies between leading electronics industry companies proclaiming their support of U.S. conflict minerals legislation while business associations were lobbying against it.

In the year ahead, more attention is likely to focus on ensuring greater consistency between lobbying positions and respect for international standards. The commentary to UN Guiding Principle 16 is an important reminder of why this issue matters:

“...just as States should work towards policy coherence, so business enterprises need to strive for coherence between their responsibility to respect human rights and policies and procedures that govern their wider business activities and relationships. This should include, for example, policies and procedures that set financial and other performance incentives for personnel; procurement practices; and lobbying activities where human rights are at stake.”

Further dialogue and joint action will be needed to address and eliminate potential conflicts between company advocated policy positions and their policies on human rights and determine cases in which they can use their political influence to promote greater protection of human rights by governments.

Ensuring responsible investment in conflict-affected and 'high risk' areas

The partial lifting of sanctions on Myanmar, the emergence of South Sudan as the world’s newest nation, and political transformations in northern Africa have made these emerging economies potentially attractive destinations for foreign investment.

Markets understand emerging economies represent uncertainties and risks. But it is vital for companies – and markets -- to understand the human rights challenges inherent in investing in high-risk environments.

With growing understanding of what can go wrong in fragile environments, business will have to ensure that its investment in these countries will be responsible. Such calls are increasingly coming from the host governments within the countries.

Home governments have also reacted through executive actions and legislative means, and reminded investors of the due diligence steps they should undertake so that their actions do not cause or contribute to conflict. As with similar measures in the past, there is no guarantee they will eliminate human rights abuses. But the increasing use of executive orders, legislative means, and soft law declarations by international organisations and governments show that states are reasserting their obligation to protect human rights.

Companies have the responsibility to comply with international norms and standards, so that the impact of their activities is ultimately positive. Businesses will have to carefully examine the legacy of past abuses to avoid becoming complicit in their continuance, or exacerbating tensions. Governments – in home and host states – will have to work together to guide business conduct, so that the due diligence steps outlined in the UN Guiding Principles are implemented. It will be in the interest of companies to transfer skills and resources, and build capacity of local businesses in conflict and high-risk areas so that they too adhere to international standards.

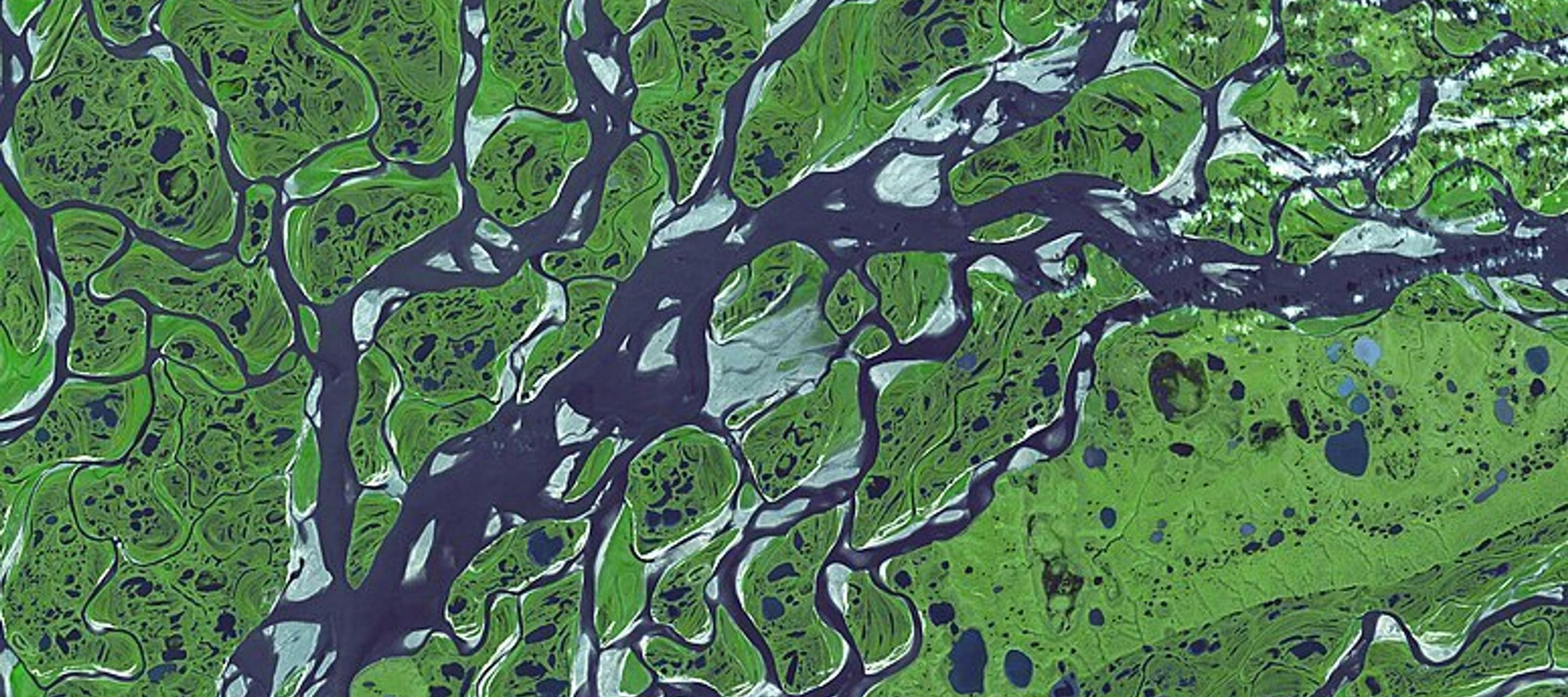

Addressing the impacts of land and water grabs linked to transport, fishing, security, mineral extraction and other sectors

Global concern over sustaining food supplies and maintaining access to water resources has led many businesses to increase investments in land and agriculture. Companies investing in infrastructure such as roads or airports, or developing extractive industries, or building tourism projects, also need access to land.

In a world where many customary owners of land do not possess legal title to their land, and where many farmers practice shifting cultivation, the rights of those marginalized and vulnerable communities are at stake.

Lacking evidence of ownership, many communities are displaced, depriving them of their rights and livelihood, and impoverishing them further. Many companies do not wish to be complicit in such land grabs, but find state security forces clearing land without consulting communities first. Indigenous communities, whose right to free, prior informed consent is often violated, are particularly vulnerable. The UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous Peoples, James Anaya’s, work relating to the extractive sector gained increasing attention during 2012 with its calibration of what FPIC means in practice.

Aggressive investments in land, and to secure access to water, have placed livelihoods of many communities under threat. In October 2012, Oxfam urged the World Bank to impose a moratorium on new investments in land, and the World Bank rejected the call.

Even if such a moratorium is impractical, businesses that seek to use land will have to develop approaches that respect human rights. These will range from decisions not to own land to sharing benefits from projects, entering contractual or lease agreements with farmers, or returning land to original users when projects complete their life-cycle. In all cases, companies must guard against involvement in forced eviction or any actions that may lead to violence.

The voluntary guidelines on land tenure of the Food and Agriculture Organisation, the performance standards and guidance notes of the International Finance Corporation, the report of the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to food on land use and fisheries, and the work of the UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights implications of development-based eviction and displacement all collectively show a growing body of international norms and standards that apply to human rights challenges related to land.

Businesses that disregard the standards will find themselves increasingly at risk of potential liability. Companies should also look at the work of organisations like the Corporate Engagement Program/CDA who have integrated rights-based approaches and frameworks in advising companies on how to consult with communities.