What is ‘social value’ in the built environment?

21 August 2024

What is the built environment?

The built environment – the places where people live, work, and interact with others – has a defining influence over our ability to lead healthy, fulfilling lives.

What is social value?

Social value refers to the net positive impacts that an action can create for society and communities beyond purely financial returns. This can be understood as benefits to the community that derive from an improved built or natural environment, positive impact on health and wellbeing, social inclusion, cultural enrichment, etc. all which ultimately improve the quality of life of people.

Decisions about what gets built, where and how have major implications for people’s lives and the planet. In recent years, ESG (Environment, Social, Governance) frameworks have emerged as a useful way to measure the sustainability impacts of business activities. Clear metrics and methodologies have emerged to quantify environmental impacts, however grasping the term ‘social value’ and then developing instruments to measure and quantify it has been proven to be more challenging.

In these attempts, a big emphasis is usually placed on the creation of social value, implying an ‘additional’ value that can be created on top of the built environment and its social fabric. While indeed social value can and should be created in many ways, it is important to not overlook the already existing social value that communities treasure in their already-existing built environments, which can either be enhanced or harmed by new projects.

How do measures of value affect human rights in the built environment?

Current measurements of value vary greatly by location, urban regime, and local culture, resulting from different priorities, metrics, legal and regulatory frameworks, cultural norms, and other financial, environmental and political factors.

However, the dominant approach globally is a narrow emphasis on financial value – which has commodified and financialised the built environment and its decision-making– often at the expense of social and environmental value. All around the world buildings, land, and infrastructure are treated primarily as financial assets, like commodities that are bought, sold, and traded for profit (financial value), rather than as spaces for living, working, and community interaction (social value).

In practical terms, this means treating housing as an asset for investment, rather than as a basic human right, prioritising short-term profits over long-term community benefits, and designing spaces, like small and inconvenient apartments, with the sole purpose to maximise profit, rather than on maximising their livability, sustainability, or social cohesion.

This predominant focus on the financial value of the built environment can undermine social and environmental value, for example, if investors want to maximise profits from housing investments, they will increase rental prices as much as possible, making housing less affordable in relation to people's wages. Other ways in which social and environmental value can be undermined is by deprioritising construction and maintenance of public spaces and community facilities that don't generate direct profit, but rather prioritising rapid development over sustainable or inclusive development that preserves cultural heritage.

In essence, when financial value becomes the primary driver for determining what gets built, how, why, and for whom in cities, it can have a negative impact dangerous for social wellbeing, environmental sustainability, and/or long-term community quality of life.

Conversely, negative impacts in social value can have negative implications for financial value. For example, in many cities, large-scale built environment projects are planned without citizens participation nor consultation with local communities, historically disregarding especially people of colour and/or in low socioeconomic status. This non-inclusive approach can result in project delays, expensive legal battles, lower local approval, increased costs, reputational damage, and reduced opportunities for future projects in that city.

A specific example is the Atlantic Yards (now Pacific Park) project in Brooklyn, New York: a large-scale development that encountered many years of community opposition and legal roadblocks due to foreseeable negative social outcomes like displacement, unaffordable housing, and inadequate community engagement. This lack of social considerations led to significant project delays, increased costs, and a scaled-back version of the original plan, which affected the project's budget and timeline.

What’s the case for a human rights approach to creating social value?

A human rights approach has already been used extensively in other areas like climate change, poverty reduction, or international development. This article highlights how the human rights approach can also bring breadth, depth and clear standards to understanding and creating social value:

- it is grounded in existing international legal standards - from civil and political rights; to financial, social and cultural rights such as the right to housing, right to health, and workers’ rights; to procedural rights such as non-discrimination and the right to meaningful participation;

- it questions and aims to reconfigure power dynamics, recognising that rights serve as checks and balances against abuses of power; and

it delineates roles and responsibilities, for example the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights set out the state duty to protect human rights, the corporate responsibility to respect rights, and the responsibilities of both to provide adequate remedies for harms caused to individuals or communities.

How can a human rights approach be applied to maximise social value?

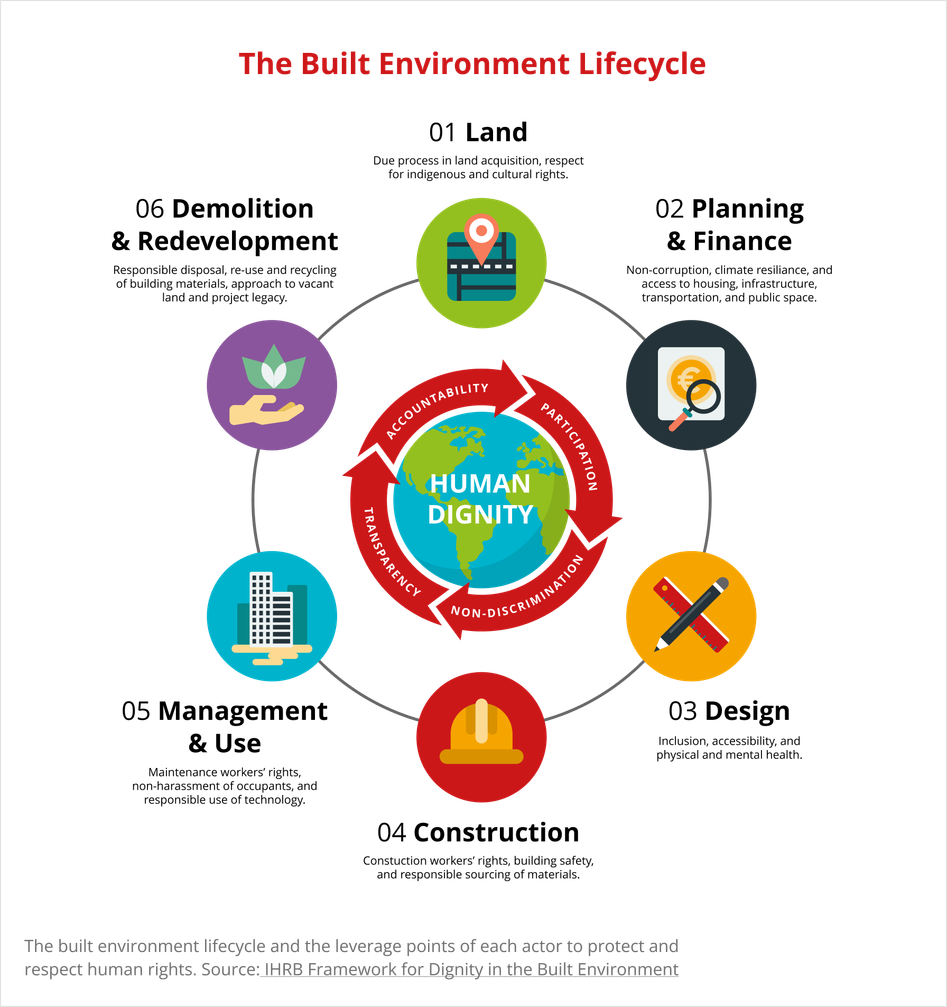

To mitigate risks to human rights and maximise social value throughout the built environment lifecycle, IHRB developed the ‘Dignity by Design’ Framework (DxD) in 2019 through consultation with multiple stakeholders. The DxD framework guides decision-making and strengthens collaboration between all actors throughout the six stages of the built environment lifecycle.

For each stage, the framework provides a high-level vision, guiding questions for implementation, cross-references to international standards (particularly human rights standards and the SDGs), and examples of action around the world.

What are examples of social value goals for the built environment?

The following is a snapshot of the high-level social goals the Dignity by Design framework provides throughout the built environment lifecycle:

- Land

No-one is forcibly evicted from their home, in accordance with international standards. Land zoning and acquisition are carried out with meaningful consultation and following due process. Indigenous and cultural rights are protected.

- Planning and financing

Urban and project planning seek to ensure the right to adequate housing (including security of tenure, affordability and habitability), and provide access to adequate infrastructure, public space, transportation, and employment opportunities. Systemic and past injustices are taken into account. Climate mitigation and resilience are strengthened, with an emphasis on participation and social cohesion.

- Design

Design seeks to expand inclusion and accessibility, regardless of age, ability, race, gender and other characteristics, and to have a positive impact on physical and mental health. Building materials are selected and sourced responsibly, with regard to their social and environmental impacts.

- Construction

Buildings are structurally safe, preventing loss of life in building collapses and fires. Workers’ rights are respected by lead companies and subcontractors, on site and through the materials supply chain.

- Management and use

Everyone has healthy, accessible, and safe spaces to live, work, and be at leisure, and tenants and users are free from harassment. The rights of workers in the maintenance, servicing, cleaning and security of buildings are respected. Technology is harnessed in a way that safeguards digital rights including privacy and freedom of expression.

- Demolition and redevelopment

Vacant land is seen as an opportunity to realise communities’ needs, while land-use changes prioritise community consultation over financial speculation. The rights of all workers involved are respected.

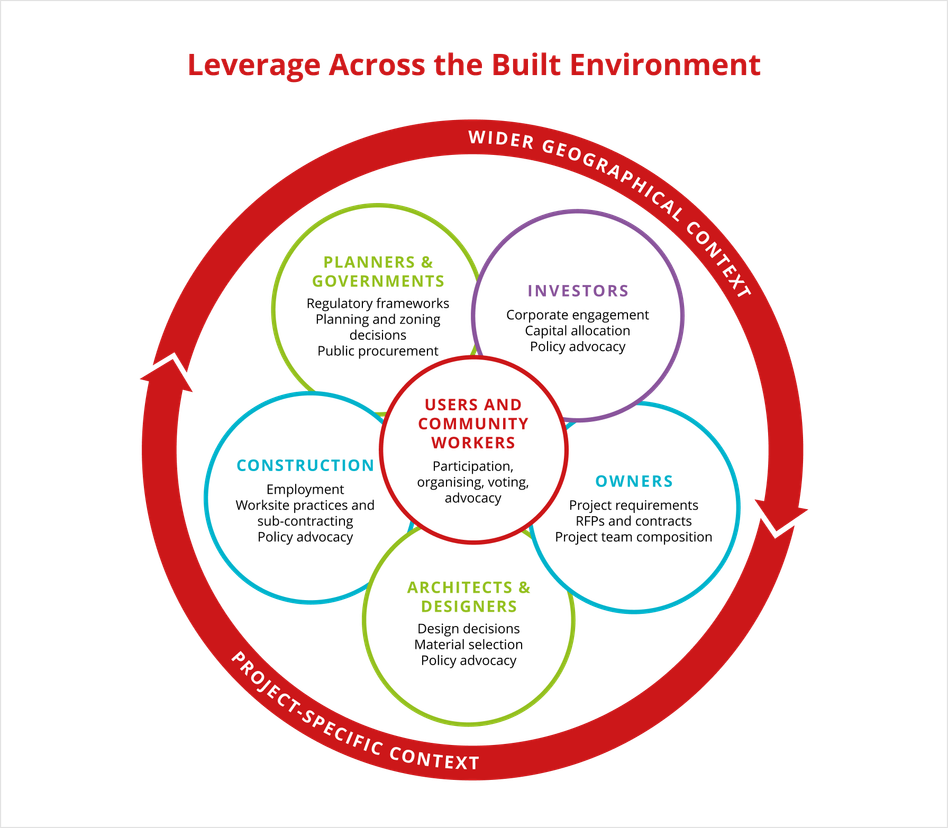

The DxD framework translates existing international human rights standards into public and private sector decision-making shaping the built environment. Hence, it can be used by various actors to maximise social value using their own specific leverage points.

The DxD Framework operates on the basis of a cross-cutting principle: all human rights standards are upheld, including the cross-cutting principles of transparency, accountability, participation and non-discrimination. Trade unions and civil society can operate freely, and all decisions are free from corruption.

Where has the ‘Dignity by Design’ framework been applied to create social value?

In the port city of Bergen, Norway, the municipality has integrated the DxD framework into a project converting a former teacher-training college building into a welcoming centre hosting services for the city’s newly arrived immigrant and refugee population. The project has contributed to change in the building process and in wider processes in the city, for example leading to stronger supply human rights due diligence requirements in city procurement contracts.

In Cartagena, Colombia, the DxD framework was employed by the municipality to guide city-wide community engagement processes for its 2022 ‘Territorial Ordering Plan’ (POT), determining the city planning strategy for the next 10 years. This followed IHRB and CREER’s (sister organisation for Latin America) local research and convening process in the city.

In Australia, IHRB and its local partner, employed the principles of the DxD framework to make a strong case in a Parliamentary Inquiry for embedding human rights principles in public procurement of infrastructure. The hearing Chair MP John Alexander expressed interest in recommending that the government establish a forum for ongoing input on these issues.

How does the ‘Dignity by Design’ framework relate to other social value approaches?

In addition to its primary grounding in international human rights and workers’ rights standards, the DxD framework has clear linkages with other frameworks:

- Sustainable Development Goals: the DxD framework, just like the SDGs, recognises the interconnectedness of social, financial, and environmental dimensions. Specifically, the DxD framework aligns with SDG11 “sustainable cities and communities” and its targets concerning affordable housing, basic services, inclusive urban planning, clean air, and public spaces. However, the various critiques that the SDGs reinforce a model of financial development that itself is a driver of many environmental and social challenges, are also important to remain focused on the root causes of these issues.

- Human security: the framework has been mapped against the UN’s human security approach with its framing of seven “insecurities”: financial, food, health, environmental, personal, community, and political.

- Human Development Index: the framework also has synergies with the Human Development Index by guiding decision-making in the built environment that relates to guaranteeing people’s basic needs, i.e. being sheltered, healthy, being able to work, learn, vote, participate in community life, etc. which can increase life expectancy, education and income levels.

- Capabilities approach: the DxD framework and human rights principles are also closely related to Amartya Sen’s capabilities approach. In both, freedom of choice of the individual – being able to choose one's own pathway – is highly valued in order to achieve well-being. Such freedom depends on what people are able to do and to be, given their environments. The and built environment are instrumental in determining people’s ‘conditions of possibility’. The framework provides guidance for built environment shapers to contribute to positive ‘conditions of possibility’ that enable people’s freedom and promote the development of their capabilities.

- “Beyond GDP” and financial model innovation: Under the current financial model (with decision-making that prioritises financial value), there seems to be a tradeoff between social and financial value. Hence, the current profit-driven logics that shape the built environment pose serious limitations to achieving human rights and the DxD outcomes. Therefore, acknowledging this root cause, and the importance of a substantive shift to re-conceptualising value, IHRB and It’s Material have assembled a map of financial innovation initiatives that seek to maximise social and environmental value, and can provide valuable insights on the path towards those scenarios from the status quo.

Find more information about IHRB Built Environment’s programme and how it promotes human rights in the built environment globally through dissemination and uptake of the ‘Dignity by Design Framework’

See also IHRB’s 2024 research project report, drawing together two years of research into just transitions in eight cities: Advancing Just Transitions in the Built Environment.