Why Fighting Discrimination is at the Heart of the Dhaka Principles for Migration with Dignity

17 January 2022

Throughout 2022, IHRB will be marking ten years of the Dhaka Principles for Migration with Dignity with guest commentaries from representatives of business, trade unions, civil society organisations, and the UN system that reflect on the continuing importance of each of the twelve individual Principles. These experts will be exploring challenges relating to each Principle in turn and discuss how faster progress can be made.

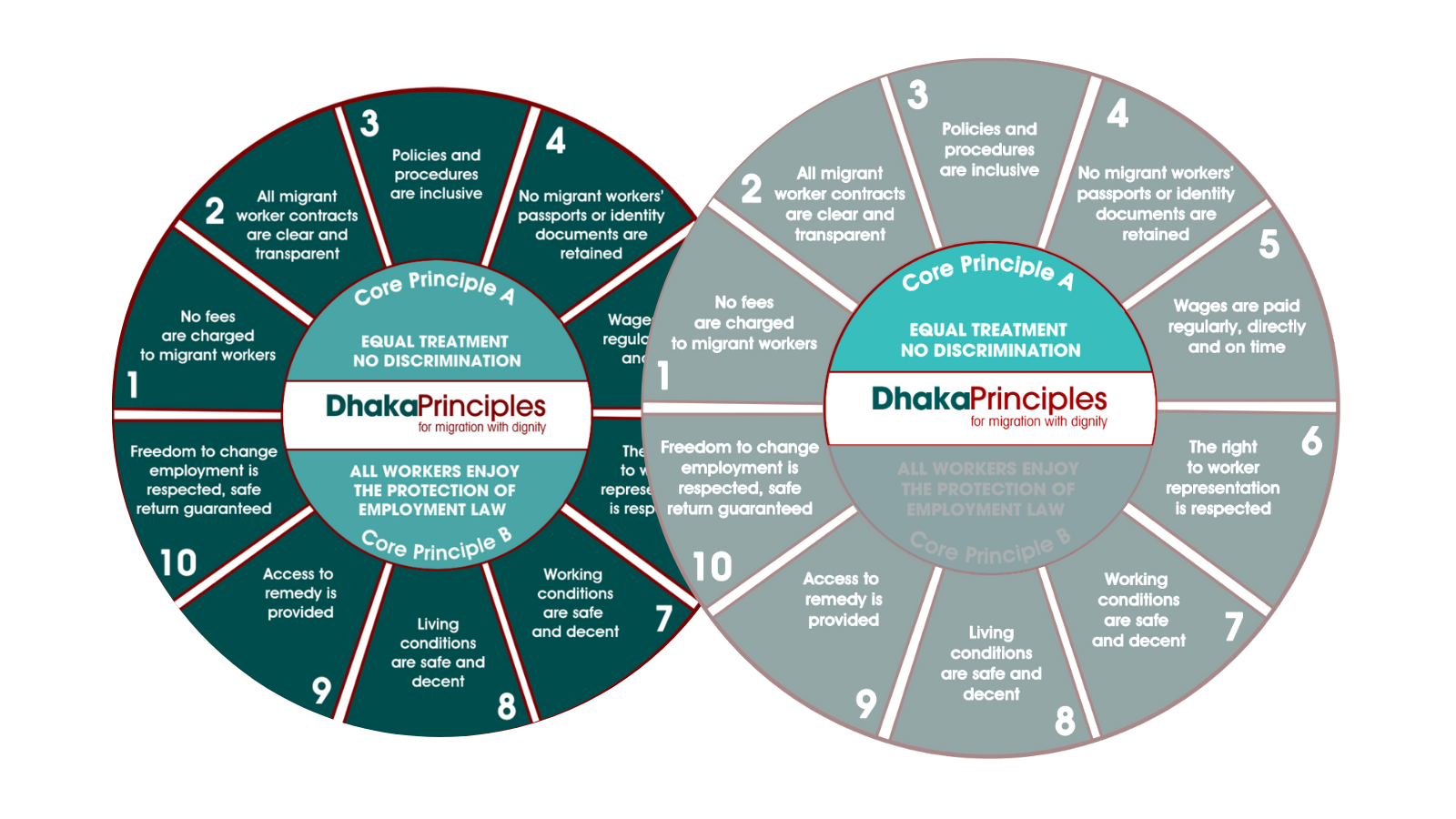

Despite the ubiquity of migrant workers around the world and the economic vitality and social gains they drive, migrant workers continue to face enormous challenges at all stages of their migration journey – from recruitment, to employment, and return home. Each Principle outlined in the Dhaka Principles highlights significant risks for migrant workers posed by those who recruit and employ them. One consistent theme runs through them all – discrimination. Its centrality to challenges faced by migrant workers is reflected in its position as one of two core principles in the Dhaka Principles framework.

Discrimination occurs when someone is unable to enjoy fundamental rights and is treated differently based on unjustified distinctions. The inequity and harm this creates was acknowledged in the 1965 UN Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination. Governments also recognised that migrant workers face a range of further challenges based on their migrant status through the adoption of the 1990 Convention on the Protection of the Rights of all Migrant Workers and Their Families. It remains the case, however, that despite these and related international labour standards, migrant workers continue to be discriminated against for many reasons: gender, ethnicity, religion, nationality, or regional identity, which may mean less favourable treatment across a range of work, social and community situations. Migrant status may also exacerbate prejudice against social background or caste.

Examples of discrimination against women migrant workers, who are often employed in low wage sectors such as domestic work, cleaning or care, highlights the scale of the problem. Women migrant workers may not always have control of their wages or where their remittances are spent. Some may find it hard to integrate back into patriarchal communities or families after time working abroad. Sometimes government policies – such as bans on women migrating to work in certain countries, a practice that is as ineffectual as it is discriminatory – actually make women more vulnerable, as they will inevitably continue to migrate but through informal channels.

A further shadow on the lives of all migrant workers that allows discrimination to flourish is poverty. When you have limited life options it is far harder to assert your rights. For many migrant workers, discrimination is so commonplace it is accepted as the norm and a necessary burden to be able to access employment.

The problems of discrimination for migrant workers are compounded by their migrant status. Migrant workers typically do not enjoy the same rights as citizens of the host country. They may lack knowledge, or be deliberately misinformed about their rights. Migrants may lack language skills or cultural anchors enabling them to navigate different systems or societies. Strong support networks or access to effective trade unions may also be lacking. These combine to leave many migrant workers in precarious situations and vulnerable to exploitation.

The problems of discrimination for migrant workers are compounded by their migrant status...The situation facing migrants is not improving.

The situation facing migrants is not improving. A 2019 study by the ILO and UN Women on public knowledge and attitudes towards migrant workers in Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand reported that positive attitudes towards migrant workers have actually declined over the last decade, even as overall labour migration has increased. In these countries, between 52% to 83% of survey respondents incorrectly perceived that crime rates had increased due to migrant workers, while between 41% to 68% thought migrant workers threaten their country’s culture and heritage. Heightened police presence in areas where migrant workers congregate; barriers preventing them from entering residential zones; and banning domestic workers from using facilities in condominiums also reinforce the type of stereotyping and discrimination that migrant workers commonly face.

The COVID-19 pandemic has widened these gaps in the treatment of low wage migrant workers. Policy and public discussions since the outbreak reveal that migrant workers are often segregated or viewed as second-class citizens. Migrant workers often lack adequate health coverage or other benefits, including unemployment insurance, should they lose work. As such, they are among those most impacted by the pandemic anytime there is disruption of work. The COVID crisis has brought underlying prejudices to the fore, allowing inequality – such as access to state healthcare and injustice such as wage theft and termination of contracts – to become routine.

Positive attitudes towards migrant workers have declined over the last decade, even as overall labour migration has increased...

It doesn’t have to be this way. Employers can ensure that the rights of migrant workers are respected and that their operational policies are appropriate to manage and engage a culturally diverse workforce. Companies should conduct research within their own operations to understand staff knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards their workers. Such studies can be critical in addressing negative behaviours and building healthier work environments that support the migrant workforce.

As an example, Pentland Brands, the name behind the sports, outdoor, and lifestyle brands including Speedo, Berghaus, Mitre and Canterbury, has used the Dhaka Principles to develop every aspect of its migrant worker management strategies and guidance for suppliers. Key to this and prominent in all its corporate policies is preventing discrimination against migrant workers.

Governments should take a lead from businesses that adopt the Dhaka Principles. All governments, in countries of origin and destination, benefit from the hard work of migrant workers. Those who advocate with Governments can use them to make a strong case for improvements in oversight, legislation, and law enforcement.

There are compelling reasons to do so. Demographic changes in many richer countries mean increasingly aged populations needing services from migrant workforces. The climate crisis will see many more people forced to leave their homes and cities will inevitably draw more migrants in search of work. Tackling discrimination is vital if social cohesion is to be maintained. This means designing and implementing policies that support social inclusion, including access to services, social security, health facilities, and schools.

All governments, in countries of origin and destination, benefit from the hard work of migrant workers.

Discrimination against migrant workers remains a systemic issue. We all have a responsibility to create societies and workplace environments where discrimination is challenged and where migrant workers, and indeed all workers, feel accepted and valued and are treated with dignity and respect.

.png) This month's expert is IHRB's Southeast Asia Regional Advisor Guna Subramaniam. Guna coordinates IHRB's regional Migrant Workers and Shipping programmes. This includes developing the Southeast Asia Chapter of the Leadership Group for Responsible Recruitment, with liaison and relationship-building with businesses, national governments, civil society organisations, and their participation in regional multi-stakeholder initiatives, roundtables and the Global Forum for Responsible Recruitment.

This month's expert is IHRB's Southeast Asia Regional Advisor Guna Subramaniam. Guna coordinates IHRB's regional Migrant Workers and Shipping programmes. This includes developing the Southeast Asia Chapter of the Leadership Group for Responsible Recruitment, with liaison and relationship-building with businesses, national governments, civil society organisations, and their participation in regional multi-stakeholder initiatives, roundtables and the Global Forum for Responsible Recruitment.