Top Ten Business and Human Rights Issues in 2019

13 November 2018

The 10th of December 2018 marks 70 years since the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was adopted. This human rights day also marks ten years of IHRB’s Top 10 Business and Human Rights Issues for the coming year.

To mark the occasion, we at IHRB turned to some of our partners from business and civil society with whom we have worked closely over the last decade to prepare our tenth annual list of the Top 10 Business and Human Rights Issues for 2019.

We are privileged to have contributions from Gender at Work, Building and Wood Workers International, Rafto Foundation, China Dialogue, Migrant Forum in Asia, Aviva Investors, The Commonwealth Games Federation, Centro Regional de Empresas y Emprendimientos Responsables (CREER), A.P. Moller-Maersk, and the Myanmar Centre for Responsible Business.

Our partners have focused on the issues we have identified together that will be of critical importance in the arena of business and human rights in 2019. These concerns are drawn from the organisation’s expertise, and reference the articles of the UDHR, as well as other international instruments.

As the list shows, the range of issues is vast. No single organisation, company, or human rights group can tackle all the challenges alone. Collective action is a powerful place to start. As IHRB enters its eleventh year, we are honoured to be working with these partners.

As always, IHRB welcomes your comments, feedback, and ideas.

Eliminating discrimination within workplace and across wider society

The #MeToo movement has brought the issue of sexual harassment from backrooms of workplaces to public consciousness. It highlights a growing recognition that harassment flourishes in a culture that allows gender inequality to thrive and encourages a system of discrimination and exploitation.

Although the spotlight on sexual harassment has focused on celebrities in the developed world, the issue is not limited to upper-class working women in northern countries. In fact, the women most affected by abuses of power in the workplace often belong to vulnerable groups such as migrant workers, ethnic minorities, daily wage earners, contract labourers, and child labourers, who have no realistic opportunities to call attention to these problems themselves, or secure a remedy.

As the Universal Declaration of Human Rights turns 70, the #MeToo movement has renewed calls to action for gender equality and women’s rights in the private sector. For companies, especially multinationals, accountability towards gender equality and human rights is diffused, in part because of weak legal frameworks. However, businesses are slowly recognising the importance of addressing gender equality and other diversity issues in the workplace.

In line with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, companies are expected to address ‘human rights impacts that are directly linked to their operations, products, or services by their business relationships, even if they have not contributed to those impacts’. However, businesses committed to implementing gender-responsive human rights standards continue to grapple with the issue of how to advance gender equality within complex organisations across all countries. The crisis is widespread and addressing the gaps will remain a major focus in the years ahead.

In 2018, Ashoka University, IHRB, and Gender at Work (G@W) collaborated to develop and deliver a new course that seeks to build awareness and knowledge of private sector employees on how to advance gender and human rights within their business. We will build on this partnership and in 2019, IHRB and Gender at Work will work with several other like-minded organisations and engage in constructive dialogue with private sector organisations to develop minimum standards for implementation of the UN Guiding Principles from a gender perspective, building on existing standards, including the Convention for the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), the Beijing Platform for Action for Women Empowerment, and the Women’s Empowerment Principles.

We look forward to strengthening collaboration with civil society groups and companies to pilot and test practical solutions that promote women’s rights in the supply chain and at headquarters.

Author: Sudarshana Kundu, Gender at Work

Sudarshana Kundu is interim Executive Director for Gender at Work Global, and the Country Director for Gender at Work India. Gender at Works partners with activists and researchers to end inequality and discrimination in organisations and communities.

Ensuring dignity while building infrastructure

Article 23 of the UDHR affirms that “Everyone has the right to work, to free choice of employment, to just and favourable conditions of work, and to protection against unemployment.” This Article goes on to guarantee “equal pay for equal work”, to “just and favourable remuneration” and “to form and to join trade unions” as fundamental rights.

Protecting the dignity of workers requires respect for them and for their human rights. This includes enabling rights in the UDHR that allow workers to shift their status from “victims” to actors of change.

By joining together, workers can change the balance of power. And, having power is essential to decent work, safety and health, and living wages – all of which contribute to inclusive, diverse, and vibrant communities, politically, socially, and economically. Rights in the UDHR were further developed with ILO Convention 87 on freedom of association and in Convention 98 on organising and collective bargaining.

The intimate relationship between enabling rights and protecting dignity means that the corporate responsibility to respect human rights is also about respecting workers as equal partners. Rights and respect are not abstract and philosophical. On a construction site, for example, it means being able to look the boss in the eye, refuse work that endangers life and limb, and challenge harassment and abuses of power.

In the global construction industry, human rights violations are common with extensive use of sub-contractors, exploitation of migrant workers, and an explosion of precarious, often temporary work. It is important, but not enough, to reaffirm support for human rights.

Building and Wood Workers’ International (BWI) strives to expand the space for workers to organise for rights, including by negotiating with employers, developing global framework agreements, engaging governments, and mobilising on the ground.

These pillars of our work are integrated into the overall framework of BWI’s Global Sports Campaign for Decent Work and Beyond. We have seen positive changes in several countries. In Qatar, for example, we are cooperating with the Government, Supreme Committee for Delivery and Legacy, multinational companies, and the ILO to improve occupational health and safety conditions, including through joint inspections as well as helping elected workers’ committee members defend workers’ rights.

In 2019, these and other advances will move us closer to our aim of ensuring full protection and respect for the human rights of all workers. By cooperating with our global network of partners, including IHRB, we can support workers in their efforts to have their voices heard and to defend their own rights.

Author: Ambet Yuson, Building and Wood Workers' International

Ambet Yuson is General Secretary of Building and Wood Workers' International (BWI). The BWI is the Global Union Federation grouping free and democratic unions with members in the Building, Building Materials, Wood, Forestry and Allied sectors.

Defending rights holders challenging power

The 70th anniversary of the UDHR is a moment to reaffirm commitments to human rights and those who defend them. Activists from every region continue to draw inspiration from the Universal Declaration in their own struggles at home and on the international stage. But many individuals and groups who work for human rights are increasingly at personal risk and their space for action is increasingly limited in many countries.

This year marks an important milestone in recognising the role human rights defenders play, including by shining light on abuses of power. In 1998, the United Nations adopted the UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders. It affirms that we each have a right, individually and with others, to “promote and to strive for the protection and realisation of human rights and fundamental freedoms.” Yet despite these standards, their implementation is threatened today, perhaps more than at any time since their creation. The space for global civil society has been shrinking.

The UDHR and the Human Rights Defenders Declaration are central to supporting human rights campaigners from all regions in their efforts to highlight rights violations and stand up to those involved, whether in government or in other parts of society, including business. The Professor Thorolf Rafto Memorial Prize for Human Rights has been awarded every year since 1987. It sheds light on grave and systematic human rights violations and recognises defenders who deserve and need the world's attention.

A growing number of human rights defenders find themselves in situations where they must call out the actions or inactions of private sector actors implicated in human rights abuses. Responsible business leaders must do more to ensure that those who hold companies accountable are viewed not as enemies, but instead as vital and legitimate actors in our shared society. They have common interests – in the rule of law and transparency, and it is important to search for that common ground. The Rafto Foundation, in close collaboration with IHRB, works with companies to enhance awareness and strengthen capacities to implement the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. Creating platforms of cooperation and dialogue between human rights defenders and corporate actors is at the core of this work.

New resources are now available providing practical recommendations for companies in supporting civic freedoms and promoting the rights of human rights defenders. The Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders has been eloquent in asking companies to do more. In the year ahead, we at Rafto will continue to support defenders who take on corporate rights abuses. At the same time, we’ll scale up our work with business leaders to develop knowledge and capacities needed to engage responsibly with human rights defenders wherever they operate.

Author: Jostein Hole Kobbeltvedt, Rafto Foundation

Jostein Hole Kobbeltvedt is Executive Director of the Rafto Foundation. Based in Bergen, Norway, The Rafto Foundation is a non-profit organisation dedicated to the global promotion of human rights.

Upholding rights in the face of massive investments in emerging economies

As the world celebrates the 70th anniversary of the UDHR, China has become a world leader in trade and investment, much of it in countries with important development needs but less than satisfactory human rights records. As China’s influence grows, will it bring prosperity and justice to its partner countries, or will it shelter and contribute to human rights abuses?

Through the Belt and Road Initiative, China is investing billions of dollars in infrastructure, port development, roads, energy corridors, waterways, and urbanisation in more than 70 countries. Many countries find Chinese loans and investment attractive for their lack of conditionality – in political, social, and environmental standards, and in some notorious cases, affordability. The result may boost GDP, but can also bring degradation of labour, human and environmental rights.

The record to date has been mixed. Agreements reached and contracts signed with one government can come under review when regimes change. There has been backlash in some partner countries over Chinese activities and their domestic impacts. Malaysia has cancelled Chinese projects worth $22 billion; the Maldives has experienced political turmoil related to Chinese investment; there is renewed concern in Pakistan about debt and the scale of Chinese mega-projects. In Myanmar debate continues about a postponed cascade of Chinese financed dams on the Irrawaddy; Venezuela has plunged into recession and a debt crisis, and Sri Lanka’s debt forced the concession to China of long-term rights to a Chinese-built port. All of these cases have implications for rights and well-being.

As China’s power expands, what norms and values will it promote? If China exports its own carbon heavy economic model, global efforts to avoid catastrophic climate change cannot succeed. If China does not implement international standards, they are undermined for everybody. Chinese banks and state-owned enterprises operate globally; their transparency and accountability, their respect for environmental justice and citizen participation – matter more than ever.

At China Dialogue, we recognise that China has the opportunity to promote sustainability and climate responsibility. Our association with IHRB includes scrutiny of China’s practices in the Belt and Road Initiative and information that companies need in order to adhere to the UN Guiding Principles and to safeguard environmental standards. In the year ahead, we hope to ensure that business leaders in China and around the world have the knowledge they need to engage responsibly for the benefit of all.

Author: Isabel Hilton, China Dialogue

Isabel Hilton is CEO of Chinadialogue.net and an IHRB International Advisory Council member. Chinadialogue.net is an independent organisation dedicated to promoting a common understanding of China’s urgent environmental challenges.

Safeguarding rights of workers on the move

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. So begins article one of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Yet we see too often dignity not being respected, or even acknowledged and rights not being promoted or enforced. This is nowhere more evident than in the situation facing millions of migrant workers around the world.

Migrant workers produce the goods and deliver the services on which the global economy depends. In Asia, with development and job opportunities across various sectors, there has been a steady increase of workers on the move within the region and to other destinations such as the Gulf, Japan, and Australia. Yet despite their key role in modern business, migrant workers are amongst the most vulnerable to exploitation.

In many workplaces, payment and working conditions for migrant workers fall below international standards, living accommodations are substandard, discrimination and other abuses are widespread. Women migrant workers face additional challenges. Lack of access to support from trade unions and effective grievance mechanisms further compromise workers’ ability to assert their rights.

For many migrant workers, exploitation begins at home. The common practice of paying recruitment fees to secure employment abroad very often leads to debt bondage and leaves workers vulnerable to further exploitation.

Tackling these issues is daunting but progress is possible. At a strategic level, the development of the UN Global Compact for Migration outlines steps expected of states, to improve government oversight of recruitment and employment at all stages of the migration cycle; not just protecting migrant workers but ensuring a level playing field for law abiding, responsible business. Companies have a crucial role as well to ensure effective due diligence regarding migrant workforces in their own operations and supply chains. Engagement with civil society is also key to tackling exploitation and abuse. Civil society priorities for 2019 will include:

- Promoting and advocating for ethical recruitment practices

- Building the capacities of CSOs to engage with the private sector through training programmes on ethical recruitment

- Developing a campaign around recruitment fees and cost, advocating for employers to pay the recruitment fees based on ILO standards and the outcome of the 2018 ILO Tripartite Meeting of Experts on Defining Recruitment Fees and Related Costs

- Continuing to expand the work around the Migrant Recruitment Advisor, an online review mechanism that allows workers to comment on their experiences, rate recruitment agencies, and learn about their rights, whilst also offering them an online complaints mechanism.

Ensuring protection for migrant workers at all stages of the migration cycle is not only the right thing to do, it is a business imperative. All our efforts must focus on ensuring migration with dignity and respect for rights.

Author: William Gois, Migrant Forum in Asia

William Gois is Regional Coordinator of Migrant Forum in Asia (MFA). Based in the Philippines, MFA is a regional network of NGOs, associations and trade unions of migrant workers, and individual advocates in Asia who are committed to protect and promote the rights and welfare of migrant workers.

Seventy years after the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and seven years after the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), investors still find it challenging to scrutinise human rights risks linked to corporate activities.

There is growing awareness in the investor community that corporate involvement in human rights abuses not only harms people, but also can negatively impact company performance, for example, as a result of litigation and operational disruptions from labour strikes.

A number of tools are available to help investors consider human rights risks companies face, but these often use proprietary methodologies and are not transparent. This makes it difficult to determine company performance and even harder to compare one against another.

Investors now have a more powerful instrument at their disposal to address these concerns – the Corporate Human Rights Benchmark (CHRB). Available for free online, the 2018 CHRB results ranked 101 major companies globally in the agricultural, apparel and resource extraction industries in six categories: governance and policies; due diligence; remedies and grievance mechanisms; human rights practices; reporting transparency; and responses to allegations of human rights violations.

CHRB scores are based on public information, so the difference between leaders such as Adidas and stragglers such as Prada is due to specific actions that have been implemented and reported. At Adidas, human rights are integrated into its risk management framework and linked to remuneration for relevant employees, including one of its board members. Risks are clearly identified, mitigated and monitored across the company and suppliers. Many other companies still have not articulated a clear plan to prevent abuses such as child labour, forced labour and gender discrimination within their businesses and across their supply chains.

By making its methodology transparent, including detailed information on how each company is scored, CHRB is ensuring that investors have more visibility. Over the year ahead, Aviva Investors, APG Asset Management and Nordea, which together have more than a trillion dollars in assets under management, will continue to work with IHRB and all other partners involved in the CHRB to make further progress and encourage more investors to join us.

The more information companies disclose, the easier it is for investors to assess human rights risks and opportunities. And the more investors use the CHRB, the higher the incentive for companies to disclose their human rights practices, prompting a race to the top in overall corporate human right performance.

Author: Steve Waygood, Aviva Investors

Steve Waygood is Chief Responsible Investment Officer at Aviva Investors, and Chairman of the Corporate Human Rights Benchmark, a UK-based not-for-profit organisation supported by investors with $5.3 trillion in assets under management worldwide.

Promoting rights through sport

As we mark the UDHR’s 70th Anniversary, sport is at a crossroads. Despite strides forward in recent years and several leading sports bodies lending their support to the Centre for Sport and Human Rights (CSHR) and its Sporting Chance Principles, the global sport industry faces numerous human rights challenges.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development rightly highlights sport’s role, singling out “its promotion of tolerance and respect” and contributions “to the empowerment of women and young people, individuals and communities, as well as to health, education and social inclusion”. The UN has recognised the ‘autonomy of sport’ - the concept that sport is politically neutral and has a unique place in public life to act as a bridge between communities. With autonomy comes responsibility and accountability.

Political neutrality has never meant that sport should be apolitical. The Commonwealth family was a bulwark in the fight against South African Apartheid in 1970s and 80s. Today’s Commonwealth Sports Movement is no less committed to being a transformative force for good and collective impact. The Commonwealth Games Federation’s (CGF) strategic vision is to build peaceful, sustainable, and prosperous communities globally, underpinned by good governance and respect for human rights. We are actively applying the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights across our operations, but we also strive to be a movement built on ‘social purpose’ measured by sustainable impact - not simply a ‘Games Owner’.

CGF’s partnership with UNICEF at Glasgow 2014 Commonwealth Games, for example, helped raise £6.5 million to support the rights and opportunities of over 11.7 million children in 53 countries. Our UNICEF collaboration also helped embed child safeguarding at the Samoa 2015 and Bahamas 2017 Commonwealth Youth Games respectively, and lay a foundation for safeguarding initiatives at future Games. On women’s empowerment, the Movement finally achieved medal parity based on gender at Gold Coast 2018 and strives to ensure that half of sport technical officials across a range of sports are women. We remain committed to absolute parity in officiating at future Games in partnership with our international federation colleagues.

We strive to not avoid or look away from the difficult salient and systemic issues. We took an advocacy position on LGBT+ Rights advocacy at both Glasgow 2014 and Gold Coast 2018, where in Australia our national member promoted a campaign supporting same sex marriage legislation. During Gold Coast 2018 the Movement also took steps on the journey of post colonial truth and reconciliation with the Commonwealth’s indigenous people, and are prioritising community cohesion as an area of impact ahead of Birmingham 2022.

During 2019, we will continue these efforts in cooperation with IHRB and all partners involved in the new Centre for Sport and Human Rights. The Commonwealth sports movement embraces its role in promoting and respecting human rights, especially at a time when rights and freedoms are threatened and principles of fairness and equality questioned. We look forward to continuing to collaborate with organisations and people sport industry wide on this important work and endeavour.

Author: David Grevemberg, The Commonwealth Games Federation

David Grevemberg CBE is Chief Executive Officer of the Commonwealth Games Federation.

Forging remedy in post-conflict scenarios

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights affirms that all people “are equal before the law” and are entitled to “equal protection of the law.” The UDHR also includes the right of everyone to “an effective remedy” for acts violating fundamental rights.

These provisions, in UDHR Articles 7 and 8, are critical in realising all other rights. But ensuring their implementation, particularly in post-conflict scenarios, remains an enormous challenge.

Forging equal access to effective remedies in countries emerging from conflict, like Colombia, requires nothing less than restoring the exercise of rights that have been disregarded or violated. With respect to the role of business, it demands clear expectations and compliance standards to ensure that private actors contribute to redressing negative impacts and play a constructive role in contributing to truth building and historic memory, reconciliation, and reparation processes under a restorative justice approach. This includes taking necessary measures to assess, repair, and compensate harms linked to business activities and working with institutions to restore respect for rights often neglected during armed conflict.

There are not clear standards on how business should provide for or contribute to effective remedies in post-conflict contexts. Business leaders should recognise the importance of taking steps beyond compensation, and making a difference as a positive societal force towards peace and coexistence. Some in business now understand that they should contribute locally in providing grievance mechanisms within their operations and support effective remedies for people most affected by conflict. More work is needed to ensure conditions are in place to resolve future disputes, and this is especially relevant to improving business-community dynamics.

In line with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, State grievance mechanisms, both judicial and extra-judicial, should constitute the basis of a seamless broader system. Under weak governance conditions common in post-conflict situations, functional interactions between state and non-state grievance and remedy systems is essential. More businesses are investing in operational grievance mechanisms, yet their effectiveness is highly dependent on assuring complementarity with governments duties to provide access to remedy.

In the year ahead, increased efforts by a range of actors are needed to strengthen access to effective remedy in countries emerging from conflict. In Colombia, CREER is working with partners on the construction of an integral remedy system understanding at the same time the dynamics and needs of a post-conflict scenario in order to build bridges between businesses and communities.

Author: Germán Zarama, Centro Regional de Empresas y Emprendimientos Responsables (CREER)

Germán Zarama is Senior Researcher at Centro Regional de Empresas y Emprendimientos Responsables (CREER), a regional hub in Colombia affiliated to IHRB.

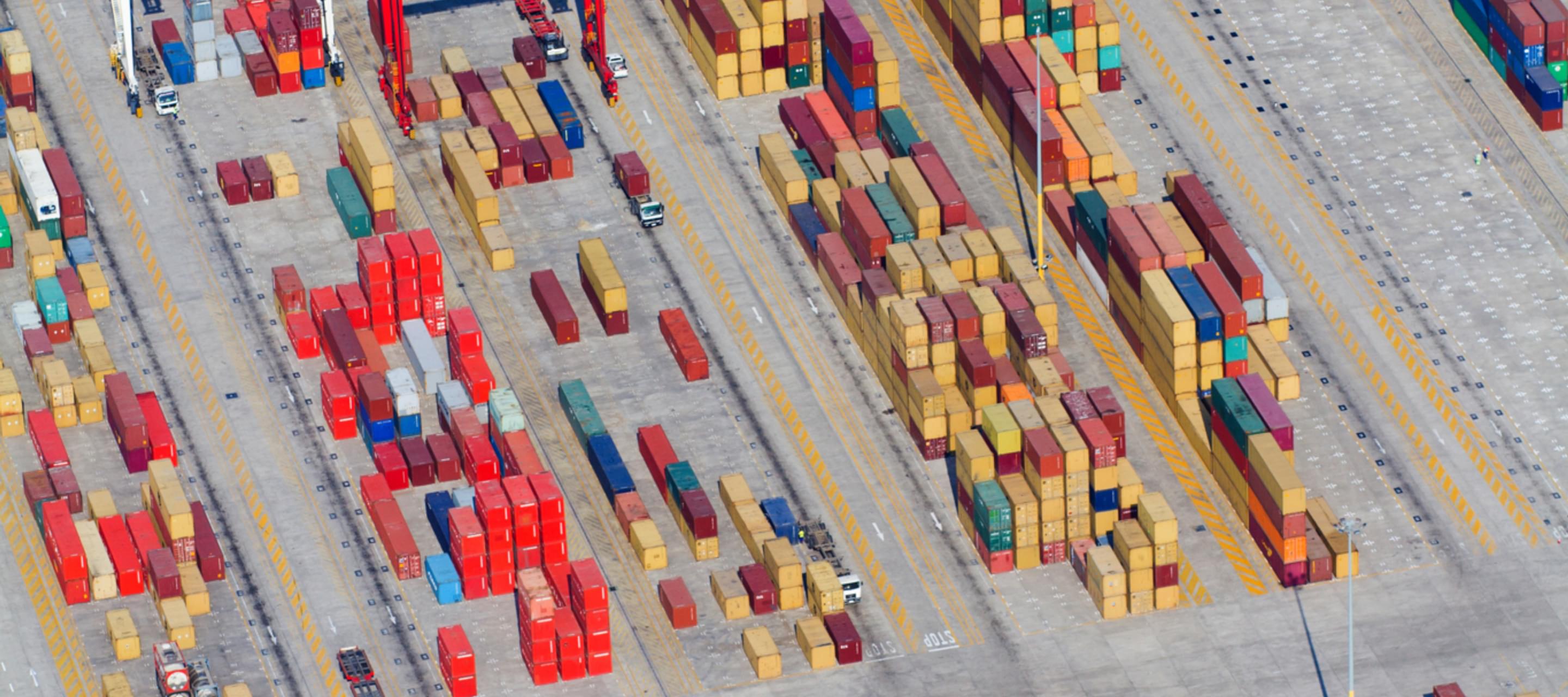

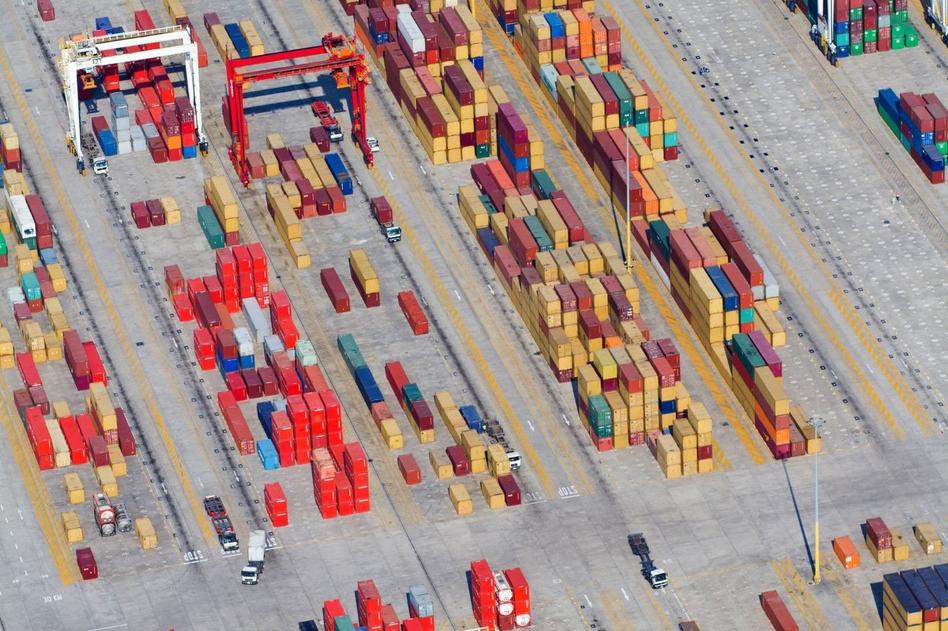

Harnessing technology to respect rights across trade and transport chains

On the 70th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, there is much progress to celebrate but also a sense that the future is not what it used to be. Tectonic plates of trade, technology, and geopolitics are shifting.

As a global leader in transport and logistics, the purpose of Maersk is to enable trade. On trade and human rights we are particularly watching two trends: the need to make trade more inclusive and the impacts of trade digitisation on human rights.

First, on inclusion. Extreme poverty is among the greatest affronts to human rights and we can be the first generation to end it. Without trade, average real incomes would be half what they are today and even less for the poorest. Articles 23 and 25 of the UDHR affirm that we all have the right to work and to an adequate standard of living. Making these rights a reality relies to a significant extent on open trade.

But trade can have adverse impacts on people, in particular those whose jobs change or disappear. Where these impacts are not met by inclusive public policies, the social contract for open trade is undermined. This is not just a matter of fairness. Lack of inclusion has also contributed to eroding the share of global incomes going to workers causing economies to slow. In the new industrial revolution, being pro-business means being pro-labour.

Second, on digitisation. Increasingly, trade and tech are linked. We all know that in the near future our refrigerators will restock themselves based on our consumption patterns, budgets, and offerings from digital supermarkets. Combined with a censor in your bin, it will help you minimise food waste and make your diet more climate friendly. Now imagine that is how all global trade will eventually work. Digitising trade holds vast potential for making economies more productive and sustainable.

Meanwhile, the pitfalls are equally obvious. They include threats of what data will be collected and how it can be used or misused. Moreover, exponential technologies have a potential to create “winner takes all or most” outcomes in both the private and public realms. Risks of excessive market concentration and mass surveillance are a concern for free marketeers as well as human rights defenders. Human rights and the rule of law are essential safeguards to keep the playing field level and fair for people as well as business.

Seventy years on from the UDHR, the futures of trade and human rights are closely intertwined. In 2019 and beyond, more dialogue and joint action will be needed to address these critical topics. As Maersk we value the leadership of IHRB in shaping global conversation on topics that are highly material to the future of our industry.

Author: Allan Lerberg Jørgensen, A.P. Møller-Maersk

Allan Jørgensen is Lead Sustainability Advisor, Social Impact at global container logistics company A.P. Møller – Maersk.

Embedding international standards in new democracies

2018 was a bad year for human rights in Myanmar, and in particular for Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, and others in conflict zones. Civil society, trade unions, and the media all reported shrinking space and reduced freedom of expression.

Business surveys report a fall in investor confidence, and a becalmed economy. However, a new Companies Act introduced greater transparency and accountability, and greater opportunity for foreign investment. This has been incorporated into Myanmar’s Investment Law, although there is a long way to go for the requirements to be put into practice.

The Myanmar Centre for Responsible Business and a group of international investors has begun a dialogue with government on what respect for human rights means at a time of triple transition, in peace, politics, and economics. There continues to be a high risk of businesses being associated with rights abuses in Myanmar, particularly in areas affected by conflict, or discrimination, in law or in practice, including Rakhine State.

Like the recommendations to business from the UN’s Independent Fact Finding Commission, dialogue between companies and government has been anchored in the UN Guiding Principles and other international standards including the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights, now active in Myanmar. The new OECD Due Diligence Guidance on Responsible Business Conduct was also launched in-country.

However, 70 years on from Burma signing the UDHR, Myanmar still struggles with human rights. The right to freedom of expression has been a particular challenge for a party elected by a landslide after decades in opposition, who are now being held to account for a stagnant transition.

Freedom of expression has been a particular challenge for one company. Facebook has homework to do in 2019, assigned both by the human rights impact assessment it commissioned, and the UN Fact Finding Mission (FFM), which gave the company nine recommendations compared to two for all other businesses.

One of 2019’s most closely watched developments will be the decision by the European Commission on whether or not to suspend on human rights grounds Myanmar’s tariff-free access. Ending the current policy would reduce EU market pressure to respect the rights of half a million workers in the apparel sector but unfortunately have no impact on the wider problems in Rakhine and elsewhere.

Business may be the one remaining driver of reform in this new democracy, not least as the private sector, including local companies, must respond to markets and investors expecting good corporate governance and respect for international standards. Myanmar’s civil servants, military, political, or religious leaders do not feel the same market impacts.

Author: Vicky Bowman, Myanmar Centre for Responsible Business

Vicky Bowman is Director of the Myanmar Centre for Responsible Business (MCRB). MCRB is an initiative to encourage responsible business activities throughout Myanmar. The Centre is a joint initiative of IHRB and the Danish Institute for Human Rights (DIHR).