Top Ten Business and Human Rights Issues in 2021

9 December 2020

On international human rights day, December 10th 2020, our Top 10 Business & Human Rights Issues for 2021 reflects a tumultuous year of pandemic-driven impacts on nearly every facet of life – from health to the economy, from the workplace to global trade. IHRB’s annual forecast for the critical business and human rights issues that need urgent attention in 2021 is as stark as it has ever been.

Our 2021 Top 10 list reflects on the ongoing and unprecedented implications of COVID-19 across five key areas: redesigning supply chains, preventing the misuse of COVID-related technology, the crisis of crew change at sea, mass-scale theft of migrant workers’ wages, and uncertainties over the future of the modern workplace.

It also highlights five critical issues beyond the immediate effects of COVID-19 where the business and human rights agenda will demand attention in 2021. They collectively represent deep-seated challenges: the resurgence of state-imposed forced labour, growing climate-driven migration, race-based discrimination at all levels, increasing divides over business standards in key governance areas, and the need for financing just transitions toward a net-zero world.

As always, we welcome your comments, feedback, collaboration, and ideas.

Resilience for All

Redesigning Supply Chains for a Pandemic-Altered World

With 20/20 hindsight, the vulnerabilities of supply chains to a global pandemic were clear to see – situated far from reach, concentrated in certain locations, and with limited visibility into operations even for major buyers. From fashion and retail to transportation, tourism, electronics, hospitality, and entertainment – buyers and suppliers were unprepared for the catastrophic disruption of shuttered businesses, locked down economies, and global trade on pause due to COVID-19.

These economic impacts also involved significant human cost. The estimated 450 million people working in supply chains are often in extremely precarious situations. They typically experience poverty-level wages, unsanitary and unsafe working conditions, little to no social protections, and often hold other characteristics – such as being women, primary caregivers, or migrant workers – that make them even more vulnerable.

As buyers were cancelling and postponing orders in 2020, or demanding price reductions and rebates from suppliers, it was workers who were often bearing the brunt. Countless reports arose of jobs lost en masse, non-existent state-supported severance and furlough schemes, stranded migrant workers, unpaid overdue wages, and COVID-19 being used as a guise to hamper union activity.

Prior to the pandemic, many businesses were already beginning to reconfigure their approach to sourcing – diversifying suppliers, onshoring or reshoring manufacturing and production, and digitising to make supply chains more visible – in part as a response to growing trade conflicts, in particular between the US and China. So 2021 will most certainly see supply chain transformation, but now rapidly accelerated by the events of 2020. “Resilience” will be the name of the supply chain game, focused on managing market change through simplified and more responsive distribution networks, cash flow cultures, end-to-end visibility, and what-if forecasting. But “resilience” must ultimately mean more than protected bottom lines. Workers’ safety, security, and stability must be at the heart of these transformed, more resilient supply chains.

The lesson of 2020 is that if supply chains are at risk then supply chain workers are at risk. The opportunity of 2021 is to place worker dignity at the centre of supply chain transformation plans. This includes a social contract that reflects the modern world of work, complete with a labour protection floor for all workers safeguarding their fundamental rights, adequate minimum wage, maximum working hours, and health and safety guarantees. It is no small order, but the opportunity for truly transformational change has come with this once-in-a-generation pandemic.

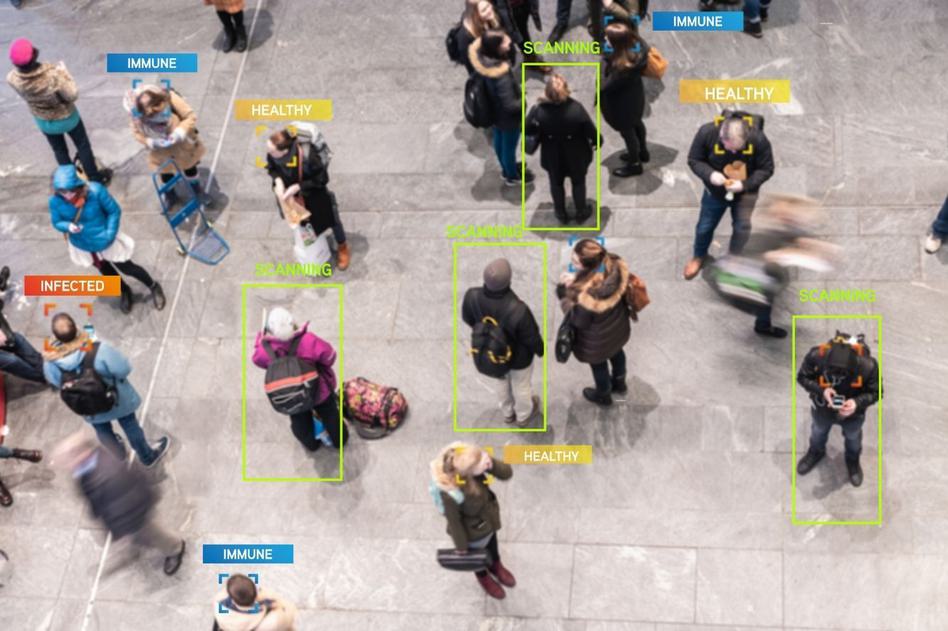

Tracking & Tracing

Preventing Misuse of COVID-Related Tech

Preventing and reducing the spread of the COVID-19 virus is a public health priority. Over a million people have died, and although early reports suggest vaccines will be available by early-2021, it will take time before we learn about their long-term effectiveness.

Targeted lockdowns significantly reduced exposure and death rates. Human rights law permits states to impose restrictions at the time of a public emergency. Social distancing, isolating those exposed to the virus, and testing, tracing, tracking and treating the sick all continue to be legitimate priorities. However, protecting health can clash with the right to privacy and the right to political participation, and also raises the risk of other civil liberties – such as freedom of expression, security of person, and freedom from restrictions – being curtailed. Certain human rights are derogable, but certain core rights are not.

Human rights risks have grown as governments deployed crime prevention methods and technologies to tackle the spread, in some cases treating patients as potential criminals. The regulatory framework is inadequate. COVID-19 responses in many instances suffer from lack of transparency, and there are questions over accountability and surveillance. Adding further complexity, tests for the virus are not always accurate. Some policies go too far in monitoring people, alongside concerns about responsible business conduct. Employee monitoring, including movement and proximity tracking is a mounting concern. Tools such as QR codes, electronic anklets, and bracelets, technologies like facial recognition, geo-fencing, and drones have been deployed, ostensibly to prevent spread, but may themselves lead to further risks to rights protections.

Companies that use or deploy such technologies are central actors in this context, as the effectiveness of these tools rests on the assumption that everyone has a smart phone and access to high-speed networks. The technology is not fail-safe; it is approximate (identifying location, but not elevation), and people can game the system (for example, by carrying multiple phones). App developers access and retain far more data than is strictly necessary. This is infrastructure for surveillance, not health-care.

In the year ahead, companies developing these and other technologies to combat COVID-19 will have to demonstrate that their products are necessary, proportionate, applied in a non-discriminatory manner, and legal. Responsible tech companies will need to work with privacy experts and human rights lawyers to ensure that in trying to build a healthy society they do not end up constructing a surveillance state.

Stranded at Sea

Resolving a humanitarian crisis

As the consequences of COVID-19 spread around the world through 2020, transport and logistics came into sharp focus as a critical sector, ensuring that food, medical supplies, fuel, and other essential goods continued to be delivered. With 90% of goods transported by sea, seafarers represent the lifeblood of the global economy. Yet as lockdown and travel restrictions continued, crews were increasingly prevented from coming ashore for fear of them spreading the coronavirus.

2020 is culminating in a humanitarian crisis at sea, with over 400,000 seafarers “stranded” aboard ships. Many have worked nine months straight (and counting) beyond their contracts, unable to return home. A similar number of workers urgently need to join ships to replace them. Suicide rates among seafarers have increased, and physical and mental fatigue, anxiety about loved ones, and lack of connectivity to keep in touch are all exacerbating the crisis. Compulsory unpaid long working hours and off-contract are leading in many cases to situations of forced labour.

The potential for serious accidents on ships with overworked and stressed crews increases daily. The logistical and cost implications of ensuring crew changes are significant – the rules for port restrictions, flight availability, border controls, and visa requirements vary from country to country – yet the consequences of leaving seafarers to shoulder the burden are unacceptable.

Numerous organisations have urged governments and port authorities to develop protocols on efficient crew change, including a joint letter from the heads of UN agencies. The International Transport Workers’ Federation has been working tirelessly to assist stranded seafarers.

Shipping companies and customers are calling for action. The CEOs of 30 global brands signed a letter seeking urgent measures to protect seafarers’ wellbeing and rights by unblocking sea routes. Numerous initiatives and protocols are being developed to address the crisis.

Pressure will increase in 2021 on governments to address the crisis. Companies must act too. There are reports of some shipping customers refusing to authorise deviations from contracted shipping routes, unwilling to share the additional cost or delay of crew change. Charterers in particular are urged to adopt and implement where necessary BIMCO’s crew change contract clause. Companies relying on ocean transportation must push for humanitarian relief for seafarers. Like health workers who have been rightly praised for their professionalism during the pandemic, the seafarers who keep supply chains moving, often at the cost of their own rights, must be fully protected.

Wage Theft

Standing Up for Migrant Workers in the COVID Crisis

Prior to COVID-19, migrant workers were already amongst the most vulnerable in the world to various forms of exploitation. One of the most common forms of exploitation is witholding or theft of wages. Wage abuse can include illegally low rates of pay, different pay for different workers doing the same job, failure to pay overtime, false accounting, and unwarranted deductions amongst others. These practices have become deeply embedded in how some global supply chains operate, a normal part of doing business, resulting in false price points for goods and services dependent on degrees of exploitation.

The pandemic severely escalated this situation. While some brands and retailers committed to pay in full for completed orders or those already in production, others responded to the crisis by cancelling orders or paying suppliers substantially reduced prices. This had an adverse financial impact on suppliers, and in turn their workers. Urgent reports arose throughout 2020 of workers far from home losing jobs, being forced by employers to take unpaid leave or reduced wages, confined in poor living conditions, and given little choice in whether and when to repatriate.

As the impacts of COVID-19 became apparent, many companies seemed to consider it acceptable – and that the consequences were negligible – if they simply did not pay due wages or adhere to employment contracts, instead laying off or standing down workers. Thousands of migrant workers faced the dilemma of giving up wages owed to them to return home, or to stay abroad with no work and no money - often in countries that do not have or offer access to social safety nets.

Many migrant workers are still struggling – months on – with the dilemma of exercising their right to return, while others remain stranded in cities or border areas without access to services or support, living in precarious conditions posing as quarantine facilities.

In the year ahead, the response to COVID-19 and promises to build back better must include greater access to justice for migrant workers caught in the continuum of abuse that makes up modern forms of slavery, in particular financial redress for lost wages. The Justice Mechanism proposed by leading migrant rights organisations in response to COVID-driven events is an important indication of what workers around the world are demanding. And in so doing, the iniquitous system that allows workers to be treated with such disregard may finally be irrevocably broken. Wage theft is part of the process of modern slavery. It is time it came to an end.

The Office

Making the New Workplace Work for People

COVID-19 has changed how we work. It has led to re-examining the tools we need to work, the technology at our disposal, and how we understand work-life balance. This has significant implications for human rights and will continue to be a focus in 2021.

Working from home sounds simple and easy, but by some estimates, only 42% of economic activity can be performed from home. COVID-19 reminds us that even in the middle of a global health crisis, essential workers are needed to grow food, load trucks, and distribute groceries; sick and injured still need transport to hospitals, where nurses and technicians and doctors treat them; cities still need cleaning; trains and taxis and buses need to run; firefighters and police officers still need to respond.

The pandemic requires a rethink of workplaces: how should we design our cities, office towers, and work environments?

Social distancing norms require more space between work-stations which could lead to bigger offices. For legal reasons, companies may scan the temperature of employees on arrival and monitor employee movements within premises, raising challenges about data retention and privacy.

Companies may decide to invest in intrusive surveillance technology to monitor how employees work from home – sensitive research and intelligence jobs will actually require this, and that too raises significant privacy concerns.

Factories that rely on assembly-line production will redesign their shop-floor to expand space between individual units, possibly making factories more humane. Some companies may no longer need physical space, with some reduction in the carbon footprint because fewer workers will commute. But such changes may have adverse impacts on the mental health of isolated, atomised workers. Companies will have to reimagine health and safety, to ensure their staff working in an environment which is not within the company’s control is nonetheless consistent with employee well-being and mental wellness.

Changes to the world of work for women will require special consideration. Evidence shows how women in abusive relationships face increased vulnerability if they spend prolonged periods at home with abusive family members. Companies will have to offer safe spaces for women, and access to day-care or other caregiving facilities, and respect their right to a family life in setting tasks or targets to achieve.

The year ahead will need greater attention to ensuring that redesigning workspaces and ‘building back better’ are centred on people and their human rights.

Forced Labour

Leveraging Against State-Imposed Human Rights Abuse

Forced labour is often associated with exploitation of workers in private sector supply chains. It is an age-old issue, linked to slavery and patterns of economic exploitation, that has seen a resurgence in recent times. Companies may also be directly or indirectly associated with compulsory labour or other human rights abuses imposed by governments. Previously, the forced mobilisation of public sector employees to work on cotton farms in Uzbekistan was widely reported. More recently, allegations of North Korean labour in Chinese factories producing personal protective equipment have raised concerns about linkages with procurement by governments around the world.

One case in particular rose to prominence in 2020, with research connecting vast networks of “political education camps” in China’s Xinjiang region to the supply chains of 82 well-known global brands.

In response, over 200 organisations spanning 36 countries issued a call to action pressuring brands and retailers to exit the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, based on evidence of widespread forced labour. Human rights organisations and investors filed a petition urging the US Customs and Border Patrol to prohibit imports of all cotton-made goods linked to Xinjiang.

Company and industry responses include public statements condemning forced labour, and pledges to undertake due diligence of suppliers in and outside of Xinjiang, as well as commitments to suspend activities and cease relationships associated with Uyghur labour. In recent weeks, major business associations have called for new joint efforts to address this situation.

The persecution of Uyghurs extends well beyond Xinjiang, and beyond the risk of forced labour in supply chains. It includes mass surveillance, arbitrary detention and torture of individuals, forced separation of children from parents, and enforced disappearances and killings, among other violations.

While the responses and commitments seen in 2020 are welcome, they are not enough. Tracking supply chains and tracing products and materials linked to such forms of exploitation might help preserve the integrity of brands, but systematic, state-imposed abuses will require a broader joint strategy from companies, governments, investors and human rights groups.

The year ahead must see more effective strategies including targeted state-to-state engagement and collaborative partnerships involving all relevant actors. Responses should also prioritise renewed calls for universal ratification of the ILO Forced Labour Conventions and Protocol, increased use of ILO monitoring mechanisms and other forums to report abuses, as well as increased transparency in due diligence processes, and restricting trade of commodities and goods produced with forced labour.

Climate Migration

Responding to the Reality of Displaced Communities

Climate-related migration, both internally within countries and across borders, is on the rise due to increased flooding, storms, and temperatures. At present, 1% of the world is a barely livable hot-zone. By 2070 that portion could go up to 17%.

The issue will increasingly be in the spotlight in 2021 in the lead up to the UN Climate Change Conference COP 26 in Glasgow and will continue to gain in urgency.

In 2020, the UN Human Rights Committee considered the case of Ioane Teitiota who sought refugee status in New Zealand for himself and his family due to the risks they faced in their Pacific Island home of Kiribati. Sea-level rise caused by global warming was contaminating water supplies and harming agriculture. Overcrowding was causing a housing crisis and leading to violence. In its landmark decision on the case, the Committee set an important precedent by affirming that governments may be prohibited from sending people back to home countries that pose immediate threats to life due to climate change.

All business sectors will need to confront the realities of climate-related migration – from finance and insurance, to energy, engineering and construction, to technology. Companies that fail to take comprehensive action on the human impacts of climate change will face growing risks to their long-term sustainability as well as legal action. At the same time, there are opportunities for companies that embrace the need for such action.

Policy responses must acknowledge migrants’ agency and the complexity in decisions to move, as well as the differing ability of people to move. The 2020 World Migration Report calls for measures that ensure: people are enabled to choose whether, when, and with whom to move; access to livelihood opportunities and to remit resources that enhance adaptation; and the ability to move in a dignified, safe, and regular manner.

Responses to climate migration must address factors driving people from their homes, including action to reduce emissions, slow the pace and scale of climate events, and enable context-specific just transitions. Strengthening resilience in the predominantly urban areas where climate migrants move to will also be critical, including non-discrimination and inclusion, decent employment opportunities, and investment in infrastructure and services. The year ahead will likely see more attention to challenges facing climate migrants and the need for human rights approaches as part of responses by governments as well as in corporate operations and supply chains.

Race Matters

Addressing Discrimination at All Levels

The Black Lives Matter movement rose to the top of the global agenda in 2020, as incidents of shocking police brutality in US cities captured worldwide attention, and sparked protests across the US and beyond. There is a long history of police violence in the US, with certain groups, such as black people, disproportionately impacted. Racial violence is not unique to the US, as a recent incident in Brazil shows.

Companies responded to the crisis in multiple ways, including by expressing support, donating money, pledging to hire more candidates from minorities, dropping controversial products, changing names of brands, and examining diversity efforts in their recruitment policies. One company candidly said that dismantling the idea of white supremacy is the task and silence is not an option. Many faced calls for further action.

Changes are long overdue, and scrutiny of corporate conduct will continue to grow in 2021, including calls to demonstrate how companies are hiring more candidates from racial minorities or ensuring that black employees remain in the company. More will be expected of all employees on issues such as unconscious or implicit bias that might influence decisions, and deeper discussions will be required on questions over whether workplaces are racially just. Gender dimensions will take on greater importance as well, such as how black women employees have different experiences at work compared to their white women colleagues. Issues of vertical mobility within companies will also take on greater prominence, as will related challenges such as the extent to which banks’ lending practices have changed to prevent discrimination against minority applicants.

Added to these issues, the COVID-19 pandemic has uncovered links between the virus, particular groups, and types of work - as data shows racial minorities have a disproportionately larger share among essential workers in the industrial world. Are companies that employ these workers taking care to ensure they are well protected? Are programmes intended to help struggling businesses during the pandemic failing to support black-owned businesses?

There is ample evidence showing that diversity is good for business. Companies will need to demonstrate their commitment in 2021 and beyond to redoubling efforts to fight discrimination. That will require more than advocacy messages on sporting logos or redesigning websites. Society at large, around the world, will be watching the extent to which companies make black lives matter.

Standards Fragmentation

Fighting Against the Divide

The year 2020 has seen a clear sharpening of divisions over the future of international standards governing business activities in a wide range of industries and settings. Established investment and trade rules and related processes have provided great certainty for companies over the past quarter century, allowing, for example, for the rapid expansion of global supply chains and cross border economic exchange. However, these arrangements face considerable strain today as can be seen in ongoing divisions within the World Trade Organisation and in negotiations over bilateral and regional agreements.

How will new rules so urgently needed in other key areas – such as strengthening data security and digital infrastructure, responding to climate change and energy transitions, and building more inclusive and sustainable economies – be negotiated in a time of rising uncertainties, in particular between major powers like the United States and China? Will states seek to further marginalise traditional international organisations and approaches they view as limiting or ineffectual? Will they instead work to further develop and strengthen new, competing, parallel coalitions and exclusive economic zones of influence, all with potentially far less consideration for transparency and respect for human rights or labour and environmental protections?

Businesses, governments, trade unions, and civil society organisations committed to human rights will need to have a clear and strong voice as these debates continue to unfold in 2021. Calls for accountability and adherence to existing international standards will be more important than ever as geopolitical competition continues to heat up in strategic governance areas, such as the technology sector and in particular geographic contexts such as the world’s oceans. Such leadership will also be critical in ensuring fairness and equity as new partnerships form to deliver COVID-19 vaccines to all regions.

What seems certain is that a further rush to forge new standards and governance cooperation based on power politics, as well regional or ideological blocs in important sectors and contexts, could result in severe and unexpected adverse economic and social impacts, in particular for the people most vulnerable to exclusion. Such steps could further undermine the global order that has been built up over past decades and that now needs to be strengthened and reformed. Defending and strengthening existing international standards relating to business transparency and good governance, including adherence to environmental, labour, and human rights standards, will be a crucial challenge for 2021 in ongoing times of unprecedented change.

Transition Finance

Maximising the Social Benefits of Net-Zero

As we enter 2021, the global community has only ten years left to stop runaway climate change, with some arguing the point of no return has already passed unless we go beyond 2015 Paris Agreement targets and measures.

Central to avoiding climate catastrophe and moving to a net-zero economy, is the concept of “just transitions”. It is an evolving concept encompassing public policies and business action to address impacts – on workers and communities – of moves away from emissions-intensive production (the transition “out”) and measures to generate the low- or zero-emissions products, services, and livelihoods of a sustainable society (the transition “in”).

It will involve nothing less than industrial transformation, and requires significant investment to be realised. The International Energy Agency estimates a low-carbon transition could require $3.5 trillion in energy sector investment every year for decades — twice the current rate. But financial opportunities abound – green bonds for example represent a $100 trillion pool of long-term private capital, yet accounted for only 3 percent of global bonds in 2018. And at a time of colossal government debt due to the economic shocks of COVID-19, placing clean energy at the heart of stimulus plans is being recommended to help revitalise economies while supporting climate imperatives.

The costs – both financial and human – will be far more significant if just transitions fail to take hold. Financing just transitions will require a mix of levers – public, private, and philanthropic capital, with a mixture of state-led incentives and low-cost financing. Visions of a reformed global economy have been presented clearly, and financial actors have the power to accelerate the transformation in capitalism that is beginning to take hold in board room discussions.

The industrial transformation needed to achieve net-zero will therefore require a financial revolution as well. The mainstream investment focus purely on financial return must evolve. Financial institutions are increasingly considering the impacts of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues on financial return. But that is not enough.

Financial regulators around the world need to be part of the revolution, and this will require legal frameworks for impact. Concepts of fiduciary duty and related duties at the core of financial regulation must be updated to require consideration of adverse ESG impacts not just on financial returns, but also the ESG impacts of investments. And to truly realise a sustainable future, regulators must also clarify that investors have duties that not only allow for but actually require investors to integrate the kinds of sustainability impacts that will move the world toward net-zero in a socially just and sustainable manner.