Advancing human rights in the built environment in Cartagena de Indias, and insights for other cities

16 May 2022

Between October 2021 – March 2022 IHRB and CREER and Rafto Foundation carried out a research and engagement process on human rights and just transition in the built environment in Cartagena, Colombia.

This process empowered the municipality to place human rights at the heart of its new territorial plan, Cartagena, Ciudad de Derechos (Cartagena, City of Rights).

The article below describes the process, findings, and the relevance for other cities.

Context

A City of Two Faces

Home to the largest port in Colombia, with its historic walls that make the past feel present, breathtaking views over the ocean, delicious food, and amicable people, it is easy to see why millions of tourists arrive to Cartagena and its beaches of Bocagrande, El Cabrero, and Morros every year. What is perhaps a less-known face of the city, is the mesh of struggles in the inner neighbourhoods. From a first glance: a loud soundscape, complicated traffic, unmanaged waste, and asphyxiating mangroves. From a deeper look: serious social, economic, and environmental challenges faced by the majority of the population.

Therefore, Cartagena is a city of two faces: divided by income, race, neighbourhood, immigration status and more1. This segregation is exacerbated by challenges to political instability: having had 12 mayors in 10 years, including due to issues of corruption, and a relative abandonment of certain neighbourhoods, has caused people’s distrust in the government and politics in general. The result is a high degree of human rights vulnerability: exclusion from basic services like water and sanitation, affordable decent housing, and a healthy environment; as well as the right to education and participation.

Nonetheless, this situation also poses large opportunities for action and positive impact. The current administration was elected on the basis of an anti-corruption campaign and willingness to change this track record. 2022 is a key moment in time: a new 12-year Territorial Plan (POT) is in the making, and with it, the interest to improve the image of the city. For this to translate into real and significant change, human rights need to be at the centre of spatial planning and concrete projects; and avenues created for people to exercise their ‘right to the city’2.

1 Milanović, Branko. 2011. The haves and the have-nots: A brief and idiosyncratic history of global inequality. New York: Basic Books.

2Lefebvre, Henri. 1968. Le droit à la ville (The right to the city). Paris: Anthropos

Photo Credit: Alejandra Rivera

Photo Credit: Alejandra Rivera

Process

Learning from everybody

The research process that IHRB, CREER and Rafto Foundation undertook in Cartagena took place from October 2021 – March 2022. It formed part of the global work of the Coalition for Dignity in the Built Environment. The process employed four methods of inquiry:

- Desk research: initial data collection and analysis of various secondary sources with the objective to understand the local context and its social and environmental issues

- Stakeholder mapping: identification of the key actors from each sector – public, private, academia, NGOs, and communities– in regards to decision-making (or lack thereof) in the built environment

- Ten semi-structured interviews: to collect the point of view of each actor and their understanding of the social, environmental, political, and economic challenges and opportunities of the city

- Observation at three community workshops organized by the Municipality as part of their participatory process to hear the concerns and needs of the population for the elaboration of the new Territorial Ordering Plan (POT). The three roundtables attended were in Manzanillo del Mar, Tierra Baja, and Punta Canoa.

Amalgamating the diverse voices of the city, especially those of local NGOs and community groups, expanded the depth and scope of the research and allowed to learn from everybody’s struggles, opinions, and unique position within the city’s ecosystem.

This initial research phase culminated with a convening event on March 3, 2022 bringing together a diverse array of 27 organisations from the five sectors. At the event participants reviewed the research to date and delved deeper into the issues at stake, in order to inform a final paper. The all-day workshop included a dialogue in roundtables to discuss the role’s and responsibilities of each actor in the planning and development of the city; and also, a structured panel with representatives from each sector, that revolved around the existing needs of Cartagena and the vision for the near future.

At this workshop, CREER (as IHRB’s affiliate organisation in Colombia) signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Municipality of Cartagena to strengthen the collaboration between the organisations and their commitment to help advance human rights in the built environment. This MOU also serves as a framework to facilitate future actions such as technical cooperation, policy shaping, joint projects, fundraising, strategic communications, and multiple other opportunities.

Signature of the MOU, Cartagena’s City Hall, March 3, 2022 | Photo Credit: Municipality of Cartagena de Indias

Findings

A fragmented urban fabric with significant potential

Partial group of workshop participants: local actors, CREER and IHRB teams

The research yielded various findings. One overarching realisation was that while Cartagena’s three economic engines –tourism, petrol-chemical industry, and the largest port in Colombia– generate considerable income to the city, inefficient macroeconomic management has not allowed harnessing them to reduce the poverty gap.

These are some of the main challenges found in the built environment:

- Lack of planning and regulation has exacerbated social inequalities: 37% of households have unsatisfied basic needs and a large part of the population lives in risky, unhealthy or polluted areas

- Speculative, rapid, non-participatory urbanisation, specially megaprojects, have not adequately considered the sociocultural context where they operate: such as the ancestral traditions of peripheral and insular communities, which are often grounded in practices of environmental and social resilience. This, risks dividing communities and breaking rural-urban links

- Strategic ecosystems, such as mangroves and wetlands, receive extenuating pressure from formal and informal urbanisation, and are in risk of disappearing

- Despite specific participatory activities e.g. POT community workshops originated by the Municipality, bottom-up initiatives that call for and act on participation processes are still incipient

- There is an important deficit in quantity and quality of social infrastructure such as schools, hospitals, cultural centres, etc: also, once built, social infrastructure lacks resourcing for continued staffing and maintenance

The dialogues from the multi-stakeholder workshop held on March 3, 2022 highlighted several immediate opportunities for the city:

- Strengthen the collective vision of Cartagena as a city for public good

- Strengthen active citizen participation and create mechanisms to enable it to continue on an ongoing basis

- Develop alternatives for mobility, for example water transportation, drawing on lessons from other cities

- Articulate the new POT with other territorial planning mechanisms

- Harness the economic benefits of tourism, local culture and environmental heritage in a sustainable way

- Transcend from the plethora of diagnostics of the city to concrete actions to address the problems

See also the slide deck presented at the event.

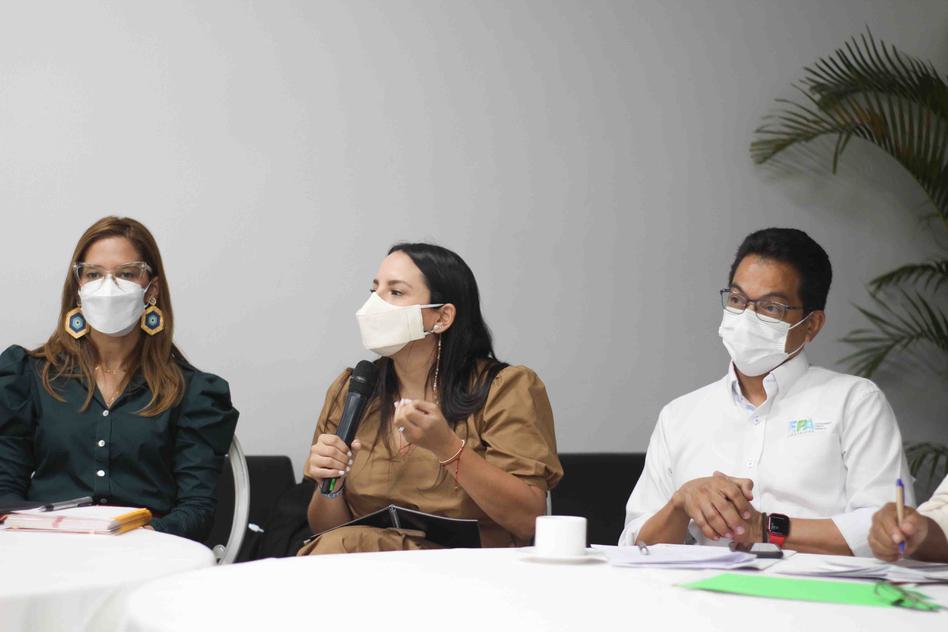

(Left to Right) Isabel Mathieu, Director Serena del Mar Foundation; Angélica Salas, Bolívar Regional Manager CAMACOL (Colombian Chamber of Construction); Javier Mouthon, Director EPA (Environmental Public Establishment of Cartagena) | Photo Credit: Yesid Cabeza Flores

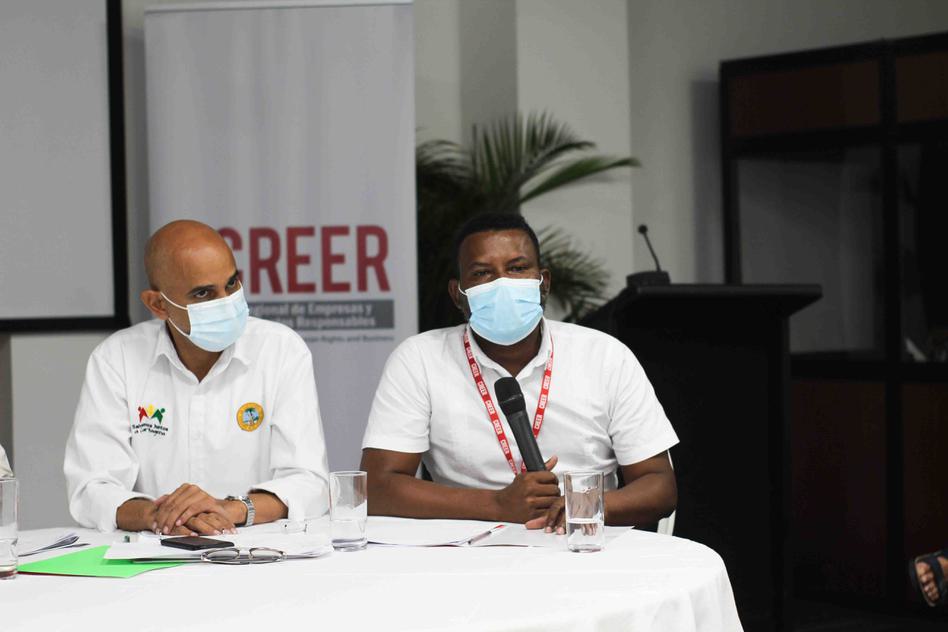

(Left to Right) Franklin Amador, Cartagena’s Secretary of Planning; Moisés Zabaleta, Tierrabaja Community Leader | Photo Credit: Yesid Cabeza Flores

Discussion among representatives from community groups, local NGO, academia and private sector | Photo Credit: Yesid Cabeza Flores

John Alexander Gallego, Director Architecture Programme, USB (San Buenaventura University) expresses his view to the other actors | Photo Credit: Yesid Cabeza Flores

Contribution

How can IHRB tools advance human rights in Cartagena’s built environment?

Expanding the approach to human rights: due to a history of violence, in the Colombian context, human rights are often associated with civil and political rights, the peace process and reconciliation. However, human rights – including economic, social and cultural rights - are also exercised or denied in the built environment depending on the way the city is conceived, planned, and constructed, and for whom.

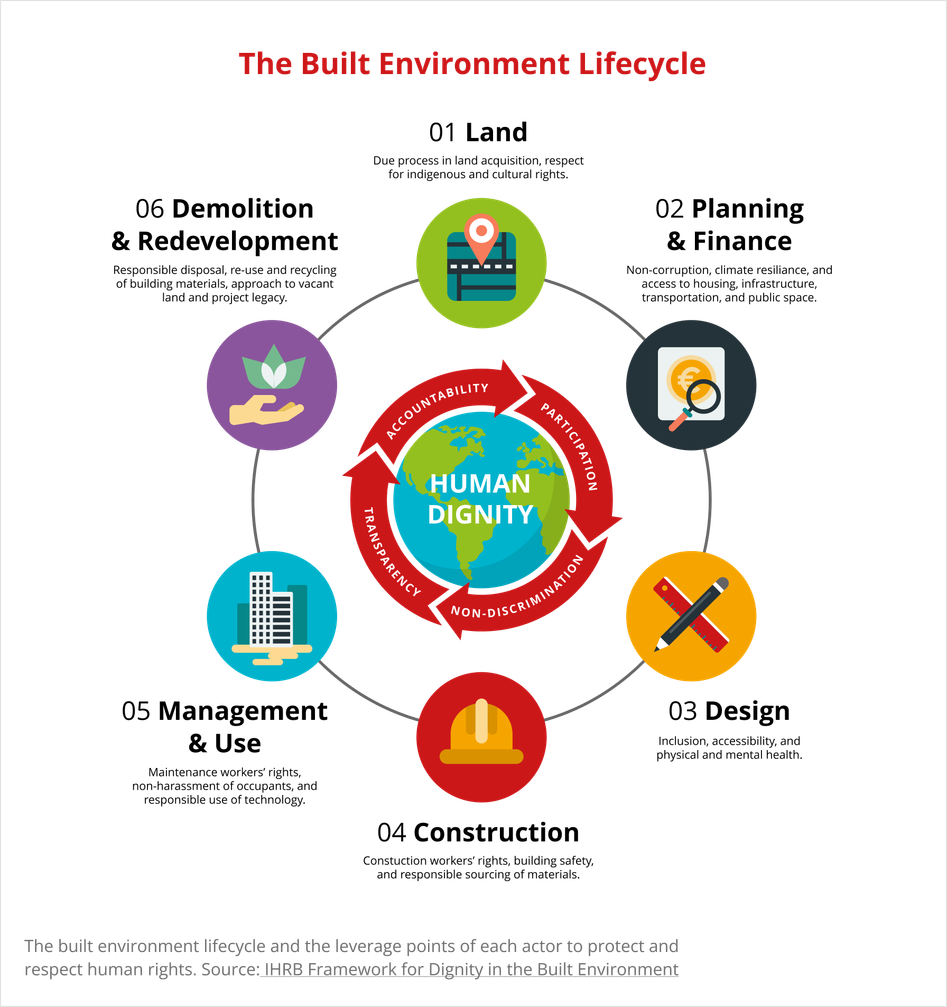

IHRB’s Framework for Dignity in the Built Environment is a tool precisely to guide decision-making on planning, financing, design and construction, and help ensure human rights are respected throughout the built environment lifecycle. It derives from international standards, but is grounded in local context. The engagement in Cartagena, and especially the signing of the MOU, unveiled the potential for implementation of this framework at two levels:

- Policy: Providing technical assistance to the Mayor's office in the content of the new POT, to integrate a human rights approach, including socio-spatial inclusion strategies.

- Project: Applying the human rights approach very concretely to a new city administrative building, with the vision of other projects in public infrastructure to follow.

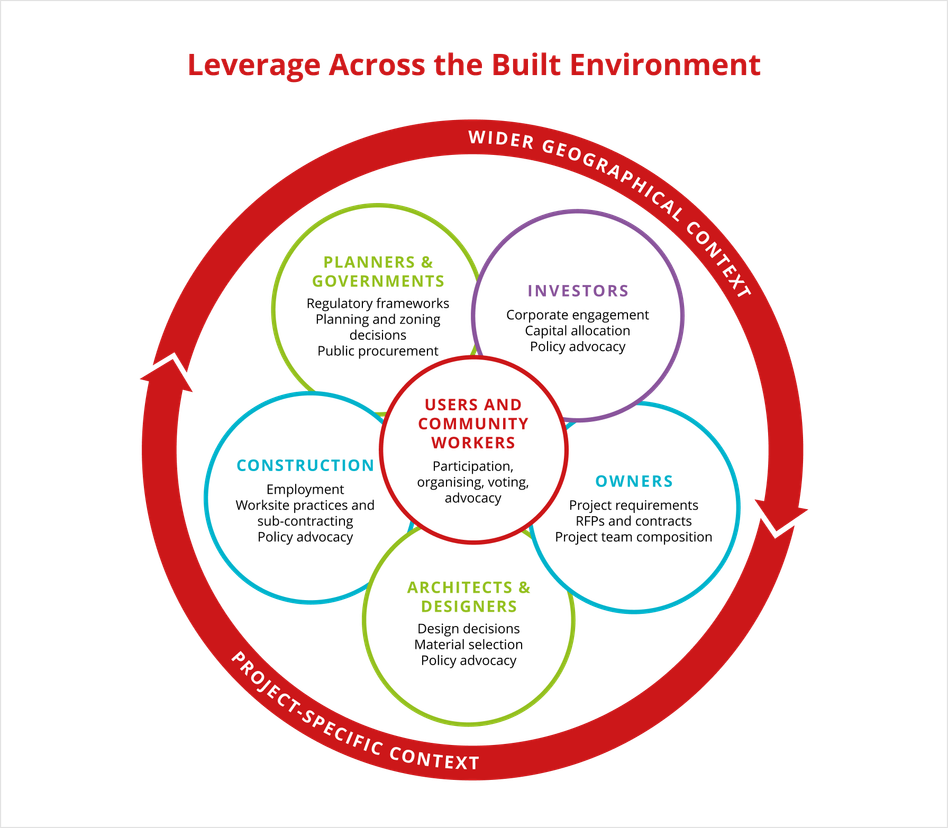

Stakeholder engagement

The process so far has shown how key is to identify and engage with all stakeholders from an early stage. It facilitates the recognition of each other’s needs, interests, value and role in the process of (re)creating the built environment. Efficient and trusted instruments for participation can facilitate stakeholder engagement.

The multi-stakeholder workshop hosted by IHRB/CREER was a demonstration of what is possible:

- It ignited dialogue that otherwise would not have happened, and allowed the actors to recognise the value that each one brings to the table.

- The workshop also fuelled the thought of solidifying this convening into more permanent and recurrent ones that could serve as a platform for participation and weaving connections.

Replicability

What other cities can learn from this experience

The research and engagement process about human rights in the built environment in Cartagena, Colombia showed the different ways in which the ‘Dignity by Design Framework’ can be implemented through a city’s public administration and a multitude of actors. Thus, it is possible to generate similar processes in other cities through:

- Assessing the various roles, responsibilities, and leverage points of the different actors around the built environment lifecycle, through a highly participatory and interactive process.

- Researching with a dual purpose: interview actors to learn about the city and their point of view on challenges and opportunities; but also, to introduce the ‘Dignity by Design Framework’ in a new context, as well as to identify specific pilot project opportunities.

- Bringing actors together to discuss and define a shared vision for the city, and potential pathways to achieve it. This includes linking city-level action to international human rights, and the cross-cutting principles of participation, transparency, non-discrimination, and accountability.

- Leveraging on national, regional and local territorial planning and development processes, such as the POT in the case of Cartagena, to incorporate the human rights approach and the ‘Dignity by Design’ Framework into urban policy

- Developing alliances for continuity. In this case, the alliances were (1) between IHRB as an international think and do tank with CREER as regional organisation; and (2) between IHRB/CREER and the Municipality (e.g. with an MOU); and with other local organisations –universities, port authorities, NGOs, and community groups– to ground the work achieved so far and ensure that its continuity is driven locally.