What's needed for a just transition in the built environment?

7 April 2023

A ‘just transition’ is the approach to decarbonising global economies in a way that is ‘just’ for people and the planet. This means transitioning to more environmentally-sustainable economies in ways that minimise risks of harm to workers, communities and countries, while reducing inequality and creating decent work and quality jobs.

IHRB’s foundational report, Just Transitions for All: Business, Human Rights and Climate Action, sets out the benefits of an approach that centres the rights and agency of workers and communities affected by transitions, as well as communities facing the impacts of climate change.

What’s the origin of ‘just transition’?

The concept of “just transition” was first championed by trade unions, and incorporates a strong commitment to social dialogue and to workplace rights. Trade unions secured a hard-won reference to just transition in the 2015 Paris Agreement, and it is further elaborated in the International Labour Organization’s (ILO) just transition guidelines, as a systemic approach to sustainability.

Climate justice and environmental justice movements have also embraced the idea of just transition - reflecting the procedural, distributive and intergenerational dimensions of justice and the significant economic shifts that will be needed to make it a reality.

This points to the fact that there is not a universal definition of what is and is not a just transition currently. For example, in recent years there have been a range of interpretations and proposed definitions by a multitude of businesses, financial actors, and industry associations. An IHRB dialogue on the state of implementation of just transition highlighted the risks of confusion, conflicting approaches, and co-option. IHRB engages closely with the ILO, UNFCCC, and other standards setters to combat this and to work toward more universal understandings in support of just transitions for all.

Where do human rights come into just transitions?

A human rights grounding can help to guide action on just transition. Human rights framing brings a clear delineation of state duties and private sector responsibilities. It also encompasses the wide breadth of inter-dependent rights: from cross-cutting rights such as non-discrimination, meaningful participation, transparency, and accountability; to the rights of groups including women, sexual and gender minorities, children, older persons, indigenous peoples, migrants and minorities; to thematic rights such as the right to physical and mental health, the right to privacy, and the right to housing.

How is just transition understood in different contexts?

The concept of just transition is gaining prominence on the international agenda. However, understanding and interpretations of just transition are nascent, non-existent, or contradictory within the homes, workplaces and neighbourhoods where transitioning economies are experienced in people’s day-to-day lives.

There is a need to engage thoughtfully in deepening and unpacking understanding at all scales - from the local through to international policy arenas - to enable the economic transformation that is needed for the future of the planet and its inhabitants.

While a “just transition” may be grounded in the foundational and ancient principle of justice, concepts and interpretations of justice vary from context to context. Just transition processes involve engaging with the complex interaction between localised realities and perceptions, and the national, regional and international dimensions with which these local realities intersect: from financial flows, to supply chains, to geopolitics.

Is there a need for just transition in the built environment?

Yes. Action in the built environment - buildings, infrastructure and the spaces between them - is a key part of ensuring a just transition. There are multiple reasons for this:

- The size and reach of the built environment sector: Real estate accounts for 60% of the world’s assets. And seven percent of the world’s workforce is in construction.

- Materials use: Current projections have global material use more than doubling by 2060. A third of this increase is attributable to materials used in the building and construction sector such as cement, steel, copper and wood.

- Carbon emissions and energy infrastructure: Around 37% of global energy- and process-related CO2 emissions come from the buildings and construction sectors. And the shift from fossil fuels to forms of clean energy will involve massive infrastructural shifts - with the phasing out and adaptations of old infrastructure, and the construction of new, bringing inherent risks and opportunities for human rights.

- Climate impacts and resilience: The residents of built areas - from hamlets to megacities - face the growing impacts of climate change, from extreme heat and weather events, to rising sea levels.

Meanwhile, the people who have contributed the least to climate change and environmental degradation in the built environment experience the brunt of its impacts. From material supply chains, to energy systems, to resiliency processes - transformation can either play out in a way that further deepens or reduces inequity.

How can we build ‘just transitions’ into the Built Environment?

Advancing a just transition in the built environment will mean fulfilling two core and connected purposes:

- Environmental purpose: Transitioning to an ecologically-conscious model that allows societal development within planetary boundaries, and:

- Social purpose: Ensuring that the benefits of that shift are equally spread and enjoyed throughout the population, and that its costs are not borne by traditionally excluded or marginalised groups and individuals.

Key procedural ingredients include:

- Agency and inclusion in decision-making, and transparency and accountability for decision-making processes.

- New approaches to value and the corresponding economic shifts.

Through its global project “Building for Today and the Future”, IHRB and partners are working to clarify shared visions for the future built environment and strengthen the pathways to get there. The table below provides indicative, illustrative elements of the contrasting ways forward.

Who’s involved?

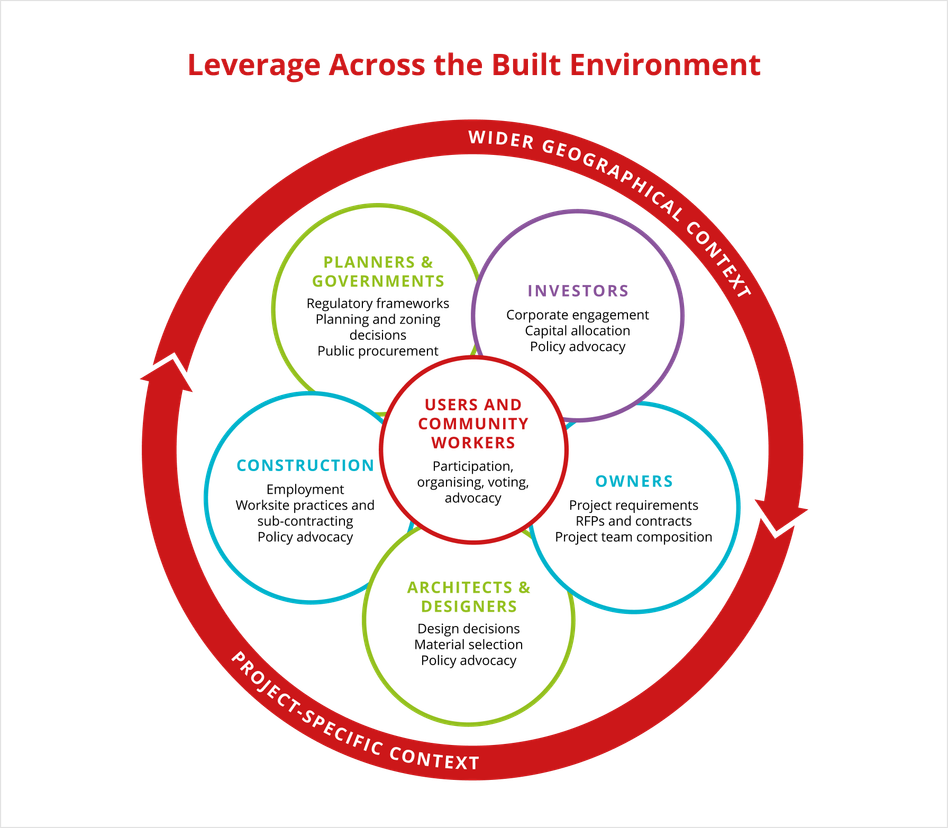

Decision-making in the built environment can be complex and fragmented, which inhibits change and progress. IHRB and partners have developed the Framework for Dignity in the Built Environment, which guides decision-making throughout the built environment lifecycle. The Framework recognises that all actors have roles they can play in generating better outcomes in the built environment - both directly and by influencing other actors in the lifecycle.

While the most power and influence lies with policy-makers and investors (and the interactions between them), the more that collective agency is expanded, the greater are our chances for fairer and more sustainable outcomes.

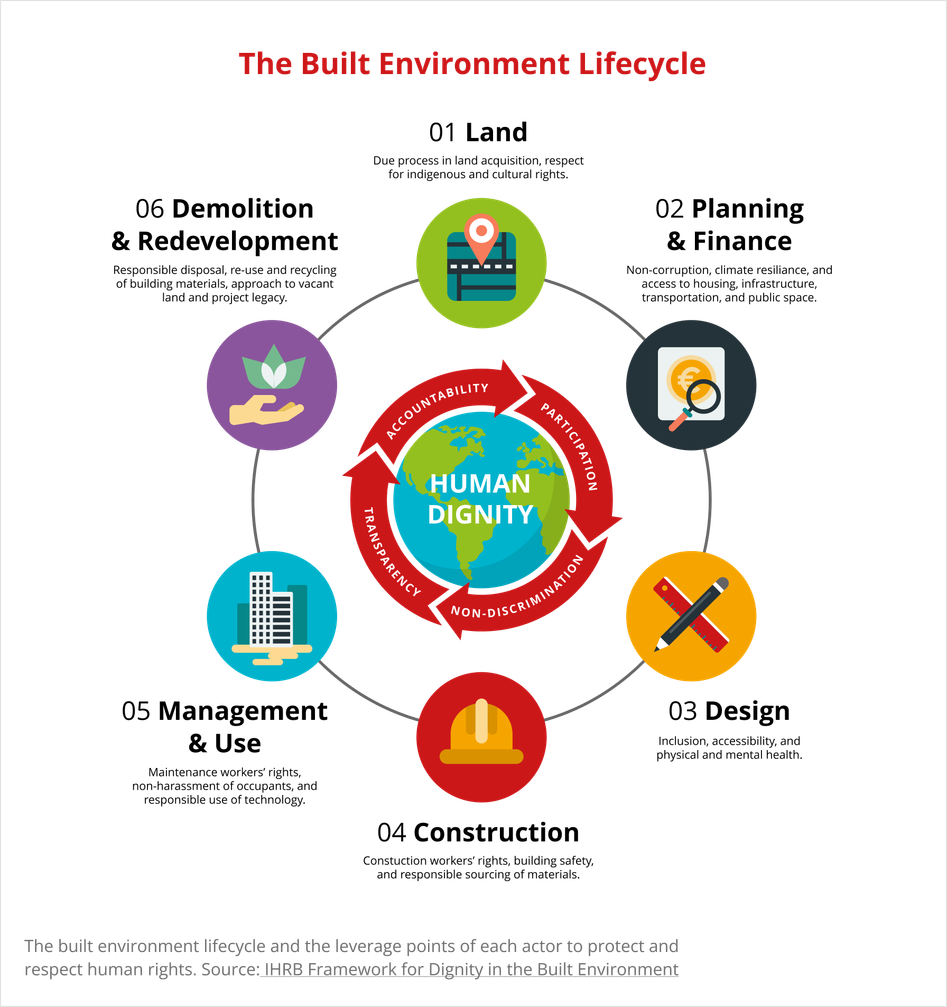

The Framework also elevates the human rights risks and opportunities at each stage of the lifecycle:

Short videos from IHRB’s event “Transforming the Way We Build” provide stakeholder perspectives on what’s needed for a just transition in the built environment: with views from civil society; construction unions; tenant unions; local government; investment; business; and academia.

What is the Building for Today and the Future project?

The project Building for Today and the Future is strengthening the agenda for a just transition in the built environment.

Specifically the project involves: action-research and visioning sessions in eight cities globally; strengthening transparency of land ownership patterns; mapping examples of economic innovation; and linking up to global-level framing and advocacy: all of which aim to contribute to change in policy and financial practices.

The project takes the breadth of human rights and decision-makers into account, with a specific focus on four areas:

- The rights of construction workers, on site and through supply chains: Including freedom of association and collective bargaining, social dialogue in the transition process, non-discrimination, eliminating forced and child labour, and ensuring a safe and healthy working environment. Building and Woodworkers International is a core partner on this theme.

- The right to housing: International standards recognise the “right to live in a home in peace, security and dignity”. The right to housing includes key elements: security of tenure, availability of services, affordability, habitability, accessibility, appropriate location and cultural adequacy - which have taken on additional significance in the context of the climate crisis, as the UN Rapporteur on the Right to Housing has highlighted.

- Spatial justice: Taking account of the spatial dimensions of who shapes, who benefits, and who risks losing out from transitions. The concept of spatial justice has been described as “fair and equitable distribution in space of socially valued resources and the opportunities to use them”.

- Co-creation and meaningful participation: Drawing on the human right to meaningful participation and on “the right to the city”, which emphasises the right not only to access what exists, but the right to change it.

Learn more about our work on the built environment

The Building for Today and the Future Project is supported by Laudes Foundation and Ove Arup Foundation.