Transforming the way we build: advancing a just transition in the built environment

1 August 2022

The built environment – buildings and the infrastructure that connects them – has major implications for climate change, inequality and, therefore, the kind of future we create.

On July 7, 2022 IHRB hosted an interactive workshop “Transforming the Way We Build” ahead of COP27, bringing the right to housing, labour rights, participation and spatial justice upfront in climate action for buildings and infrastructure. The workshop had over sixty active participants, representing worker and tenant unions, municipalities, finance, industry, academia and civil society.

Catch up with the session with the playlist below

Key takeaways

- Slowing down: An overarching message was the need for slower building processes: recognising that current rapid construction practices narrowly focused on short-term profit maximisation yield to many social and environmental challenges, from housing pressures caused by over-speculation, to unsafe building structures that put lives at risk, to over-use of materials and high-carbon emissions.

- Investing in what is needed: Slowing down does not mean not investing in the building and infrastructure that is so urgently needed in many contexts. It means taking the time and creating the space to shape the way that building happens and what gets prioritised. Shaping built environment decision-making to benefit people and the planet will involve: systemic change that expands participation, agency and ownership; harnessing public procurement and regulation; enabling innovation and effective design (including to lower the cost of environmental improvements); reducing speculation and harnessing transition finance towards “human-level investments”; and reducing disparities on the grounds of gender, ability, race, age, income, migration status and more.

- Local contexts within a global economy: Regions, sub-regions and countries contain vastly different contexts in terms of what people need more of or less of in the built environment. At the same time, the factors that influence these outcomes are often cross-boundary, particularly in terms of access to finance and the types of financial flows. A recurring message during the workshop was that strategies need to be grounded in and mindful of local contexts, while also engaging with transboundary dynamics. These transboundary elements include, but are not limited to, carbon emissions, migration, financial flows, supply chains, and global advocacy and learning networks.

- Centering human dignity: Climate mitigation and adaptation processes in the built environment are often technocratic in nature, which can limit public support and momentum for action. And yet the built environment is intrinsically connected with people’s wellbeing and opportunities to improve their lives. Taking human experience as the starting point for change can be transformative. The human rights framework is a powerful approach to do this: putting national and local governments’ existing human rights commitments and duties (from the rights to housing and health, to workers’ rights, to non-discrimination) and business’ responsibility to respect human rights into practice in the context of the built environment.

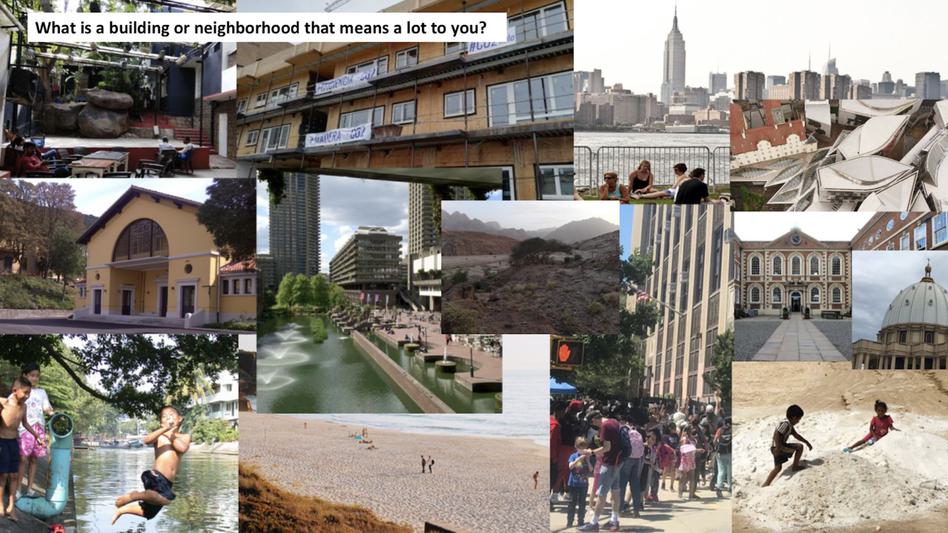

Meaningful building and places

The workshop opened with a snapshot of the specific buildings and places that participants had shared in advance of the workshop, as holding particular meaning or importance for them:

Participants’ reasons for selecting those buildings or places:

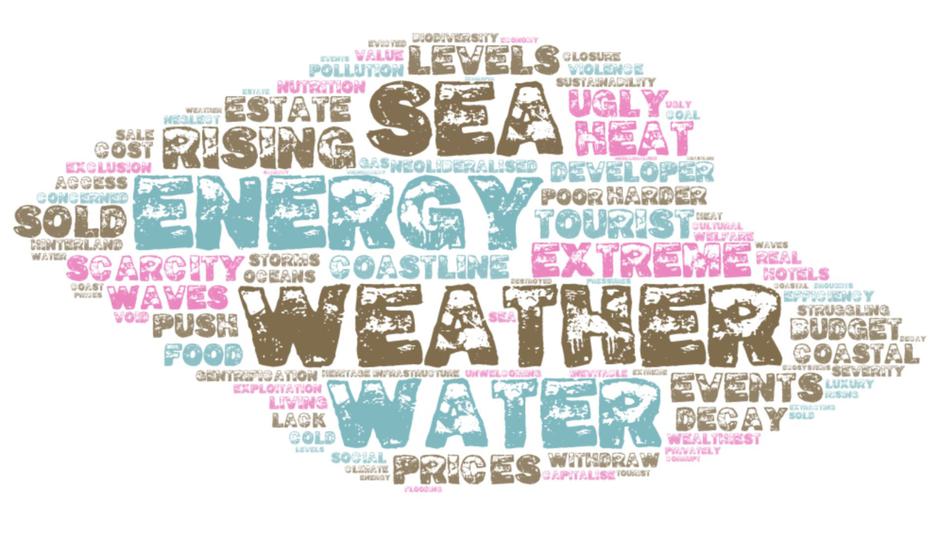

The social and environmental risks that the meaningful buildings and places face:

And the social and environmental opportunities that they contain:

Perspectives

Participants then heard brief interventions from eight perspectives representing different thematic priorities, regions and sectors. Materials from each of these organisations as well as others participating in the workshop are available here.

Patrick Allam, Legal Officer with Spaces for Change, Lagos said that one of the biggest challenges in Nigeria is the criminalisation of poverty in the name of urban renewal and environmental improvements. Strengthening land rights for poor and low-income urban residents is foundational for a just transition of the built environment.

“The built environment has to do with planning and finance. You often see investors coming in and bringing a lot of money, appealing to the public sector, and making people leave while trampling on their rights. The new apartments are not affordable for the community who lived there before. If the government can come up with housing programmes that integrate the poor and low income earners together it would go a long way in the just transition in housing.”

Linnea Wikström, Global Coordinator for Construction and Infrastructure with Building and Woodworkers International highlighted what is needed to ensure the rights of workers in the transition to a more sustainable construction sector. This includes: social dialogue; investment in training, green skills and employment support; social protection as a human right; and ensuring that macroeconomic, industrial and sectoral policies such as COVID pandemic stimulus packages take workers into account.

“Social dialogue between govts, employers and workers’ organisations is essential, because otherwise we won’t overcome barriers, realise opportunities and deliver the innovation which is what our sector needs.”

The following two speakers focused on the context within Europe.

Chiara Massarotto, Policy Officer, International Union of Tenants called for mandating tenants’ participation in building renovations. Key changes that are needed to support a just transition in the built environment include applying the principle of “housing cost neutrality”, preventing “renovictions”, phasing out energy inefficient and unhealthy buildings, and security of tenure.

“Only when tenants play a central role in the built environment they live in will the green transition be just and fair.”

Maria Boström of FEANTSA, a confederation of national organisations in Europe working to end homelessness, called for Europe’s “renovation wave” to be implemented in ways that first and foremost support the lowest income and most vulnerable residents. If this is done, it has the potential to cut low-income household’s energy costs by a third.

“If well designed, the renovation wave has potential to bring not only environmental gains, but it can also help address housing exclusion and create a more just society.”

Rebecca Wessinghage, Transition Concepts Officer with ICLEI (Local Governments for Sustainability) elevated the role of local governments. She shared a vision of cities with: spatially just distribution of benefits and sustainable, circular construction practices. Changes needed to realise this vision include municipal programs that consider circularity and social equity together; harnessing socially-responsible public procurement and social public-private partnerships; and strong partnerships across different sectors.

“Local governments can act as enablers for local market landscapes, in which: diverse enterprises engage in different aspects of the construction cycle…employers offer fair working conditions and opportunities for local residents with different skill levels, and local governments support these employment standards by providing enabling conditions for SMEs, cooperation platforms and social enterprises.”

Amira Ayoub, MENA Programmes Head, World Green Building Council introduced WGBC’s three priority areas: climate action; resources and circularity; and health and wellbeing. She called for systemic change in order to approach built environment projects in a more holistic way, involving everybody who has a stake in a project from the very earliest stages, to explore its potential, how it can educate, innovate and come up with new solutions.

“I believe that the thing we really need is to slow down, a little bit. We are all running after schedules and project timelines, to finish as fast as possible. We need to slow down, explore how we can do things better and revisit our vision every now and then. Listen to everyone and involve everyone in the process. If we do this, we will not miss someone, or leave someone behind.”

Maria Nkhonjera, Energy Researcher, The Africa Climate Foundation introduced the concept that underpins the foundation as addressing climate change while also unlocking avenues for development. She described a dual role that philanthropy can play: i. supporting countries in transforming their climate ambitions and “Nationally Determined Contributions” (NDCs) into credible investment plans, and identifying opportunities to structurally transform carbon intensive sectors such as buildings and infrastructure; and supporting catalytic projects and programs, to leverage additional quality finance.

“A key element we want to see is how we sufficiently bring in the conversation of transition finance, which is fundamentally different from other forms of finance. We see this as central to putting human-level investments at the centre of urban spaces.”

Khaled Taribieh, Associate professor and university architect at the American University in Cairo elevated the role of institutions such as universities as “anchors of change within the context of explosive urbanisation”. Universities and their students can raise issues of inclusion, accessibility, and mobility of people, through partnerships at the neighbourhood level, and with governments and nonprofits.

“[While we are in] exponential acceleration to beat the clock and provide the new houses that we are supposed to provide for growing populations, there are definitely issues that we are missing.”

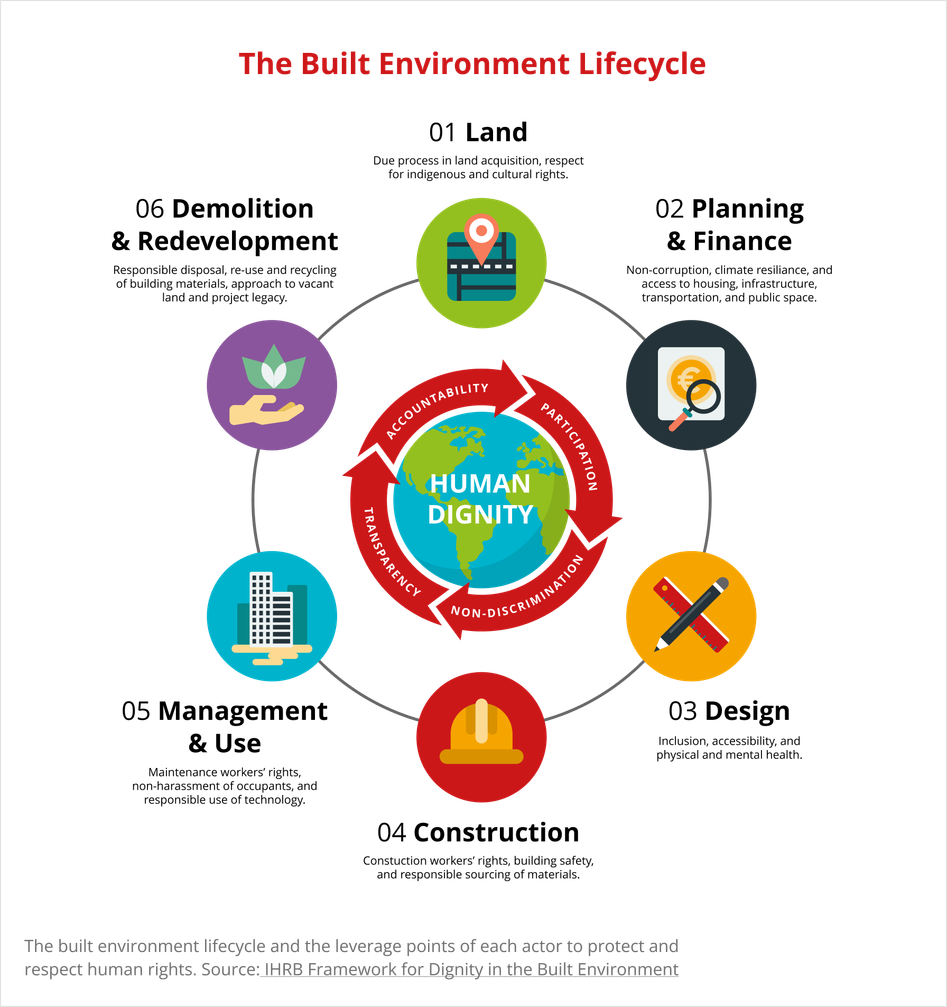

Introducing the dignity by design framework

IHRB introduced the Framework for Dignity in the Built Environment, which guides decision-making and action in the built environment in line with international human rights standards and the UN Sustainable Development Goals. It harnesses the roles and responsibilities of actors throughout the built environment ecosystem.

Break-out sessions

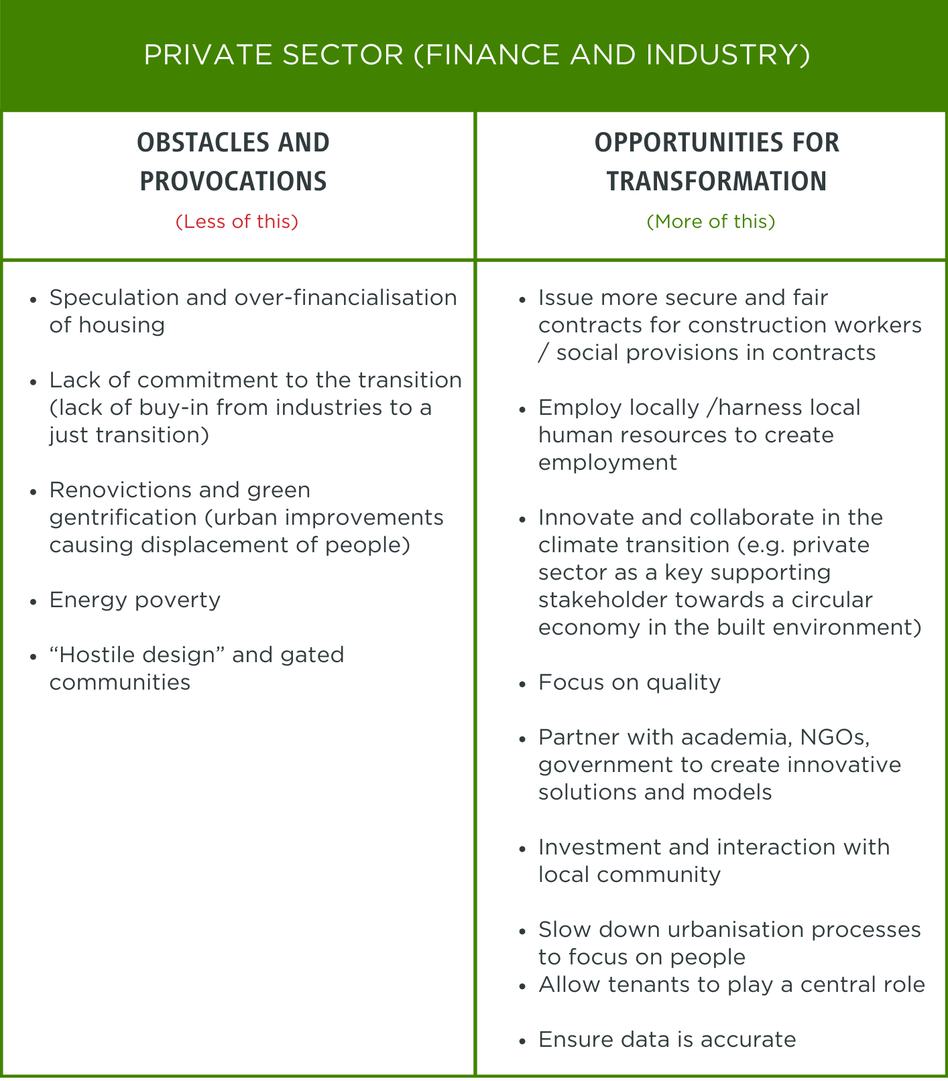

Participants shared what they would like to see “more of” and “less of” from the public and private sectors, who have the biggest leverage at the early stages of the built environment lifecycle.

Overarching points

- Participants emphasised that – as the Framework for Dignity in the Built Environment illustrates – tenants and residents, workers, local communities and community-based organisations have key roles to play in governance: it is important to centre their role.

- Participants shared the following obstacles and opportunities with regard to the public and private sectors:

Introducing the project: 'Building for Today and the Future'

During the final part of the workshop, IHRB introduced its new global project “Building for Today and the Future” which will harness research, visioning sessions and policy advocacy to advance a just transition in the built environment.

Context

The following points provide background on the context in which this workshop took place:

- Buildings contribute almost 40% of global carbon dioxide emissions, through energy use during their long lifespan, and materials used in construction; reducing these emissions is fundamental for meeting climate change goals

- Urban areas need to adapt quickly and effectively to the impacts of climate change such as increased heat, wildfires and extreme weather events, and rising sea levels

- Residents of all urban areas face barriers to the right to housing – an ‘enabling right’ because it allows the realisation of many other rights, including the right to physical and mental health, non-discrimination, and access to basic services

- Construction workers on site and through supply chains – who are often domestic or international migrants – frequently face hazardous working conditions and an erosion of their rights. Construction workers themselves also often live in inadequate housing/environments.

- Measures to mitigate and adapt to climate change in the built environment can either exacerbate or address existing inequalities. These measures include energy renovations of existing buildings, green and circular construction processes, switching to renewable supplies and strengthening resilience. These measures also need to take into account the fact that millions of urban residents still lack access to adequate housing, infrastructure and energy to cool or warm their homes.

- Addressing all the above requires transformation in the way we build . No one actor can address these dimensions alone, however all have interconnecting roles to play as reflected in the Framework for Dignity in the Built Environment: grounded in the cross-cutting human rights principles of accountability, transparency, non-discrimination and meaningful participation.

- Addressing all the above requires transformation in the way we build . No one actor can address these dimensions alone, however all have interconnecting roles to play as reflected in the Framework for Dignity in the Built Environment: grounded in the cross-cutting human rights principles of accountability, transparency, non-discrimination and meaningful participation.